Please join Yeosijae as we build a brighter future for Korea. Create your account to participate various events organized by Yeosijae.

- Insights

- |

- Northeast Asian Regional Community

[COVID-19 Crisis, a test of governance / Japan] “A deep-rooted system that requires sacrifices of individuals for the good of the social stability”

What is “the Japanese corona virus mystery” indicating?

Japanese society relieved at the decision of postponing the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics instead of canceling it.

It was on March 23 that the Japanese government admitted for the first time, there was a possibility of delaying the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics, the same day when Canada announced that it would not send its Olympic team, first country to do that in the world. Before that, the Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe had only repeated, “I wish to hold the Olympics and Paralympics in their complete form.” At the Budget Committee meeting held on the day, he finally admitted, “We may now have to consider postponement in order to hold it in complete manners.” And the next day he made an official suggestion to the IOC that the Olympics be held one year later. It was five days after the Olympic flame arrived in Japan from Greece.

In hindsight, “holding the Games in the complete form” turns out to be a sort of groundwork for the postponing. When the IOC’s announcement was made, the Japanese public was largely relieved. The office of the Prime Minister also seemed to be relieved that the Olympics would be held before September, 2021 when the Prime Minister’s term ends. In other words, it was the cancellation that the Japanese government had been so worried of, thus they took a strategic approach by reiterating ‘in the complete form’ in order to avoid it.

on the evening of March 25 (Source: EPA Yonhap News)

The fight against COVID-19 outbreak has just begun?

Japan taken aback by the unexpected crisis

Up until that time, the Japanese government and the public was reacting to the COVID-19 outbreak rather ‘quietly’, outweighed by the national concern for the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics. The outbreak was considered an obstacle to the Olympic Games so the disclosure of the information on the virus was very limited. How fast it spreads and how the response system is working have never been displayed on the main pages of the Internet portals. Although the media reported on confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the country, their main focus was on overseas cases. They were quick on reporting infection cases in China, Korea, and European countries like Italy, and the United States. Plus, the news about celebrities in other countries contracting coronavirus were out fast. Nevertheless, Japan was apparently holding back information on the coronavirus patients within the country.

Japan began to turn its attention to the virus only after the postponement was made official. On the night of March 25, Tokyo governor Yuriko Koike held an emergency press conference, saying “the current situation is a serious situation where the number of infected people may explode.” Koike may be planning a ‘lockdown’ of the city. On the same day, Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga announced that the government would set up an emergency task force based on the “Act for Special Countermeasures against the New Influenza,” which had been revised to prepare for an explosive jump in cases. Suga said at a press conference, “I wish to hold the Olympics after we completely won the battle against the virus.” On the 26th, Prime Minister Abe made a direct order to form the emergency task force under the Special Measures Act. He even indicated a possibility of declaring a national emergency, which was indicative of growing concerns about a big surge in virus infection cases on the previous day and more worrisome, the number of those who were infected from unknown sources on are on the rise.

Is the sudden jump in the confirmed cases coincidental?

In the meantime, was it really a sudden increase in the number of the confirmed cases? On March 25 when Tokyo Governor Koike held a press conference in the middle of the night, the number of confirmed patients in Tokyo was 212. A sharp increase of 41 just in one day may have caused a sense of crisis. However, regarding that Tokyo is a city of close to 10 million people and 2.8 million commute to the metropolitan area, the number is surprisingly small. Things are the same nationwide. Recently the number is increasing by almost 100 a day, it is still surprisingly small compared to the number of the infected in Korea.

A German media outlet called this a ‘Japanese coronavirus mystery’.

It criticized the number of tests are too small and at the same time, cast doubt over the efficiency of the tests, which are conducted only to those most likely to be confirmed to have the virus. Bloomberg News citied the low coronavirus death rate of Japan as wearing masks and their hygiene habits.

However, an alarm has been raised from early on that the Japanese government was intentionally passive in response to the spread of coronavirus, for fear of the virus’ getting in the way of the Tokyo Olympics. There were many occasions that raised a reasonable doubt that for the sake of the nation’s or the government’s big event, public health had been put aside. It’s strange to see government officials suddenly raising alarms and urging public alertness against the coronavirus pandemic upon the delay of the Olympic Games.

A few days ago, the New York Times published an article, ‘Japan’s Virus Success Has Puzzled the World. Is Its Luck Running Out?’ The newspaper pointed out that as of March 27, South Korea, with a population less than half the size of Japan’s, has conducted tests on close to 365,000 people, and in the meantime Japan has tested only about 25,000. The NYT also said that Japan did not put cities on lockdown nor did it adopt the kind of wholesale testing, but still has one of the slowest-progressing rates of spreading virus in the world, and raised a doubt citing an expert, “It’s either they did something right or they didn’t, and we just don’t know about it yet.”

Japanese system to exclude and isolate threats

From the onset of the COVID-19 outbreak, Japan employed “Mizugiwa Policy”, a military term for the tactic of repelling invaders as soon as they reach shore. The “Mizugiwa policy” is to block the source of infection from outside. One of the best examples of it was the virus-struck cruise ship Diamond Princes that had left more than 700 confirmed cases. When over 3,600 people were quarantined on the ship, the Japanese government literally ‘observed the situation’, just keeping up with the growing number of patients, instead of taking prevention and control measures against the pandemic. That triggered growing criticism home and abroad. The Japanese government has even refused to add up the infected passengers aboard the cruise ship to its national statistics of the coronavirus infected. Governments around the world were sending chartered planes to bring back their nationals and the Japanese government disembarked the cruise ship passengers consecutively. The US and other countries put their people that came home from the quarantined cruise ship on a 2-week long self-quarantine, but the Japanese government didn’t take any follow-up quarantine measures. It handled the virus-infected cruise ship as an external threat to Japan and did little to protect Japanese passengers and crew on board. And they are still counted separately from the national COVID-19 statistics of Japan.

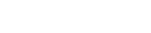

We can see the national and regional statistics and updates,

but information on the infected people and contact sources are non-identifiable.

What lies beneath this Japanese government’s response to the coronavirus pandemic is ‘separation’ and ‘exclusion’. It is another indication that Japan is a society that puts society before individuals. The report by the MHLW’s panel of experts, ‘New Coronavirus Outbreak, Its Analysis and Suggestions’ published on March 19 was carrying the same message. The experts advised the Japanese government should keep on doing what it has been doing, ‘preventing the spread of infection at the maximum level possible while minimizing its impact on society and economy’. The basic strategies they suggested were early detection and early response to infection clusters (a group of patients in close proximity in terms of both time and geography); early diagnosis of patients and improving intensive care for the seriously ill and securing health care system; and accepting behavioral changes in the public.

Experts Are Expected to Keep Social stability Under Control

For what did they make such an announcement of something that is so obvious to even those who are not experts? Their aim was to let the public know that there was an consensus among experts on ‘keeping the social and economic impact of the pandemic as little as possible.’ What it is implicitly saying is that experts are expected to talk the public into believing that they have to cooperate with the government so as for the coronavirus outbreak not to grow into a society instability factor. So the Japanese take limited tests for only those with clear symptoms and disclosing minimum amount of information on the confirmed cases as something good and required for the social stability. More specifically speaking, do not trigger public unrest and keep the screening and testing as low key as possible.

On the Japanese government website, detailed information on the confirmed cases is also classified as ‘non-identifiable’

From the onset of the COVID-19 outbreak, on the other hand, Koreans have been using coronavirus tracking smartphone applications developed in the private sector. The apps plot the locations where confirmed patients have been and help the public know whether they may have contacted any of those carrying the virus. Transparent information disclosure played a crucial role in speedy tests and tracking the outbreak. However, Japanese information disclosure has been scarce and slimy and they do not provide as detailed information of areas and places that those contracting the coronavirus have been to as Korea does. The MHLW and local governments’ websites give little information regarding the confirmed cases and detailed information is non-identifiable. The Internet homepage of Chiyoda, the political and administrative center of Tokyo provides a guideline, from which we can assume, for how much information should be disclosed or should not in Japan.-₁ The guideline says information disclosure regarding coronavirus incidences in the district should be made in consideration of protecting personal information and privacy to prevent prejudice, discrimination against patients and from causing financial damage to business owners due to unfounded rumors. The criteria for the disclosure are: 1. when the impact on the residents is presumed to be huge; 2. when it is necessary to ease the residents’ fear when a business arbitrarily discloses concerning information, then Chiyoda should get in the way and provide relevant information. Depending on the limited information provided by the central or local governments, you can not possibly find out whether you may have contacted a coronavirus patient or not. In this way, threats are kept underwater in everyday life of the Japanese public.

-₁ 千代田区「区内における新型コロナウイルス感染症患者発生の公表目安について」

Fukushma nuclear disaster silenced in the cries of ‘GANBARE, Nippon!’ COVID-19 outbreak overshadowed by the Tokyo Summer Olympics

The way the Japanese government is responding to the coronavirus crisis reminds us of the Great East Japan Earthquake. It was recorded as one of the worst catastrophic events in the Japanese history with three major disasters combined: a seismic earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear reactor meltdown. The Fukushima was an “unexpected” accident. The metropolitan area, which had heavily relied on nuclear power generation in the Tohoku region, was economically devastated by the unprecedented nuclear accident. The Japanese government evacuated more than 100,000 residents within a 20km radius of the meltdown nuclear reactor and beyond where there was a high radiation risk. It was often reported that Fukushima children who had been displaced after losing their parents and homes and families were often bullied and harassed as a ‘radiation spreader’. However, the Fukushima disaster was quickly and deliberately transformed to a national disaster. Soon the goal of reviving and restoring the society overtook the Japan with the loud and clear slogan of ‘GANBARE’, don’t give up, Nippon! GANBARE, don’t give up, Tohoku!’ In the early stages of the accident, the information about the spread of “cesium 137” was disclosed, but information regarding what and how much damage would it cause or how far radiation has spread was very limited. The Japanese government, instead, waged a nationwide campaign to ask consumers to buy agricultural and marine products from Fukushima to help Tohoku people in need. And in the process the public gradually forgot about information or the spread of the radiation. The nuclear meltdown and its subsequent impact were quickly excluded from Japanese society and alienated. The stories of displaced people who have lost their homes due to the disaster are only occasionally addressed by the media around anniversary of the Great East Japan Earthquake that comes around every year.

ad published on the Independent magazine

at the time of the Great East Japan Earthquake

Individuals Endure Inconvenience

For the Good of Social Stability

The Japanese way of crisis management to prevent threats from causing social unrest has been repeated from the Fukushima disaster to this corona outbreak. Threats have been separated and kept under water. They are something that is surely out there but invisible and difficult to grasp what it is. The public is left with whatever information the government and media offer only to get a glimpse of what’s happening around and take necessary steps on their own. However, just as the Fukushima disaster was handled and faded away in the mind of the public under the catchphrase of the national restoration in collaboration with the government, nuclear industry and media, the coronavirus crisis has been put on the back burner in the fear of postponing the Olympics, a ‘national crisis’ (a crisis for the Abe government to be exact). An implicit social arrangement was made that people endure a little bit of inconveniences that may arise from the public health crisis, to maintain social stability.

COVID-19 crisis, a testbed for the Japanese commitment to escaping from the post-war regime

Takahashi Tetsuya, a renowned critic of the Japanese government authored a book, ‘Systems of Sacrifice, Fukushima and Okinawa(Gisei no shisutemu, Fukushima and Okinawa)’, in which he criticized that the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster was a manifestation of the untold truth on the ‘public sacrifice’ underlying in the Japanese government’s push for the nuclear power following the World War II.-₂ He argued that the Fukushima disaster was not different from what had happened at the U.S. military base in Okinawa, where residents had to sacrifice under the Japanese post-war constitution and in the name of the US-Japan alliance. Takahashi viewed the national drive for the nuclear power generation and the US-Japan alliance under operation in ‘the systems of sacrifice’ and argued that the postwar Japan has been governed likewise. This ongoing coronavirus crisis confirms that Abe who has been saying he wants to escape from the post-war regime is following the footsteps of the postwar regime that sacrifices individuals for the stability of society.

-₂ 高橋哲哉. 2012. 犠牲のシステム 福島・沖縄. 集英社

If Abe truly wants to achieve his political agenda of “breaking free from the post-war regime,” he needs to overhaul the social system.

It was August 15, 1945, when Japanese Emperor Hirohito unconditionally agreed on the Potsdam Declaration. However up until the previous day, on August 14, the Japanese newspapers was hailing battle with the Soviet troops, victories of Japanese Navy submarines fighting, and sinking three of the Allied forces warships offshore Okinawa. A majority of the Japanese in the mainland, who thought they were winning a war world over as local newspapers and broadcasts told them so, was taken aback and flabbergasted at the abrupt turn of the event, the nation’s sudden surrender to the enemies. In the name of social stability, information was often provided selectively and sometimes tempered in Japan. After the war was ended, the Japanese government was telling its people that everything was done under the national emergencies to save the nation from the war and the public must understand that. And now that the Japanese government is set to take the coronavirus crisis more seriously and tackle it in full commitment, will it break itself from the previous way of handling the crises? If the Abe government genuinely wants to accomplish its goal of escaping from the post-war regime, it needs to overhaul its crisis management system. Will the post-war system of requiring individuals to sacrifice for social safety still hold good in the 21st century? It will be a moment of truth for Japan. This pandemic crisis may be an opportunity for the Japanese government to prove its commitment to finally breaking free from the post-war regime.

|

Hwang Se-hee is a Japan expert who got her Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees at Yonsei University in Korea and a Ph.D. in Law at Keio University in Japan. She specializes in Japanese diplomacy, US-Japan alliance, East Asian security, and maritime safety. During her doctoral study, she worked for three years as a student staff member in the Japanese House of Representatives. After graduation, she was a research fellow at the Japan Maritime Policy Research Foundation and a visiting researcher at Keio University. She has taught at Keio and several universities. |

< Copyright holder © TAEJAE FUTURE CONSENSUS INSTITUTE, Not available for redistribution >