Please join Yeosijae as we build a brighter future for Korea. Create your account to participate various events organized by Yeosijae.

- Insights

- |

- Global Order and Cooperation

[The Biden Era: South Korea’s Strategy ②] There is No South Korea in Washington’s Inner Circle

Taking Lessons from the Cultural Amity between Israel/Japan and the U.S.

The Two Faces of America

Four years of Trump have caused a big change in America; it marked the end of U.S. global leadership and the beginning of a divided America. President-elect Joe Biden, who campaigned with the slogan of Build Back Better, now faces the daunting challenges of COVID-19 and economic recovery in addition to the responsibilities of restoring American leadership and solving the partisan divide. How will Biden manage these different issues? With the dawn of a new era approaching, the Yeosijae examined what changes are likely to occur in the forthcoming Biden era in regards to the U.S. national security and foreign policy, U.S.-North Korea relations, and U.S.-China conflict and explored how South Korea should respond to those changes.

The Korean version of “The Biden Era: South Korea’s Strategy” series examined the current state of affairs, U.S. foreign policy, U.S.-China conflict, U.S.-North Korea relations, and trade policies. Of the five areas, we selected three to share with our international readers.

Developing effective strategies to respond to different situations in a time of change requires an accurate assessment of the current state of affairs. In this article, the first of the series, we share insights from a member of the National Security Advisory Board at the Republic of Korea President’s Office, Young-Jun Kim, who is also a professor at Korea National Defense University, to examine different issues facing the Biden administration from the U.S. perspective.

Table of Content

1. Current state of affairs

2. Foreign policy

3. U.S.-North Korea relations

been held in Washington, D.C., every year since to commemorate their relationship.

Whenever a new U.S. president is elected and sworn in, South Korean politicians and media scramble to portray themselves as the closest confidant of the new administration. Including (rather sad) information about photos taken together or emails exchanged with appointees, it has been long since their attempts to establish a relationship with Washington have become legitimate pieces of news covered by mainstream media and broadcasts. Considering America’s indisputable influences over the Korean Peninsula, it is only natural that Koreans would be as interested in its political ties with important administrative figures as they are with the U.S. elections. One cannot also overlook the fact that South Korean culture emphasizes personal connections.

Trump was an outlier that disrupted existing networks of relationships;

With Biden’s return to Washington comes a return of Democrat faces

The Trump administration came as a surprise for its lack of traditional Democrat and GOP faces. It shared little connection with countries across the world, including South Korea, in the political, diplomatic, academic, media, and business spheres. President Trump, in this regard, was a rebel. At the same time, to his supporters, he was a revolutionary. Over the years, American suburbia had developed strong resentment towards the elites—the politicians, entrepreneurs, experts, and the media—out of the sense that they have been neglected and forgotten. And taking the anti-elite sentiment into consideration, President Trump emphasized that he would part with the traditional Washington politics and not become Wall Street’s puppet. He was the “people’s president”—a Jacksonian president—in that he communicated directly with his people. If we take a moment to suppose that a politician in South Korea with a chaebol background pledged to self-fund their campaign like President Trump, it becomes easy to imagine just how much support they would receive from the general public.

The rise of the Trump administration severed ties between American elites and the world, and think tanks in Washington, D.C. were robbed of their cherished political network and funding. This made it difficult for countries to make use of their networks during the Trump era. With Biden’s victory, countries are once again flexing their muscles to demonstrate their connections with the returning Democrat administration. Just how much influence do these individual connections have on South Korea’s pursuit of national interests and America’s policies?

ROK – U.S. relations hinges on individual/fragmented relationships

As regrettable as it is, in this American era, South Koreans must be keen on their relationship with key American political figures that could shape America’s policies toward the Korean Peninsula. In fact, there is a bipartisan consensus in Korea on the need to foster more pro-Korean voices in America’s inner circles to serve Korea’s national interests. This, of course, does not mean South Korea will follow or worship America and its policies. Pro-Koreans in Washington DC are necessary for the South Korean government to communicate with the U.S. and foster understanding and support for Korea’s policies and strategies. South Koreans, therefore, had no choice but to be wary of America’s elections and their outcomes. However, as an advanced nation, we must ask ourselves whether diplomacy based on individual, fragmented personal relationships befits a country like South Korea.

Two Faces of America

A strategy to gain on both Sides

The U.S. was the world’s leader during the Cold War and its aftermath that ushered in the liberal order. It is undeniable that global trade and world order today is maintained by the foundations that America built through its influences and the establishment of the UN, IMF, World Bank, and the dollar exchange system. In light of these facts, Koreans developed two perceptions of America.

First, Koreans believe there is a good (an ‘altruistic’ side) America. In other words, we believe that the U.S. perceives itself as the world’s leader in politics, economy, military, and culture (e.g., Apple, Amazon, McDonald’s, Hollywood, Billboard, U.S. forces, and CIA; with the exception of recent discourse over American crisis) and approaches global order as the world’s leader by saving children and women from poverty and protecting people from terror, natural disaster, disease and ethnic cleansing. On the other hand, there is the bad (‘materialistic’) America. In this perspective, we assume that America’s foreign policy focuses on economic gains, much like the case of the military-industrial complex (MIC) and its role in America waging endless wars, selling arms to allies, and securing favorable market positions.

It would seem, then, when we deal with the good (altruistic) America, we would have to approach them as an ally state that upholds human rights, contributes to democracy, and reinforces U.S.-led world order. And when we face the bad (materialistic) America, we would have to engage them as business partners that strengthen America’s geopolitical hegemony and add to its economic gains (through lobbies, arms sales, et cetera).

Like every other nation, America has two conflicting sides. It has an altruistic side that seeks to combat poverty in developing nations and advance human rights, while it also has a materialistic side that inclines the nation to maintain geopolitical hegemony and economic dominance. And as mentioned before, South Korea should consider both sides as we strive to bolster our national interests and alliance. In other words, it is imperative that we appeal to both sides of America. However, Koreans often overlook this fact and take a shallow approach when we make a case for our agendas in the U.S.

The Logic of the Peace Process on the Korean Peninsula: a Narrative for only Koreans, not Universal

A recent example is South Korea’s communication strategy of the peace process on the Korean peninsula to America. Considering what America’s stance has been on the peace process last several years, we must make reflections on whether our approach has neglected to make appeals to both sides of America. Let us suppose that we argue to America that U.S.-D.P.R.K. denuclearization negotiations will bring peace on the Korean Peninsula, promote inter-Korean exchanges, denuclearize North Korea, and integrate the North Korean economy into the world market through Northeast Asian multilateral trading mechanisms. By this logic, both Koreas stand to gain a lot from the negotiations, including peace and stability. Yet, what geopolitical and economic benefits does it offer to America? And why should Americans normalize their relations with evil dictator North Korea still having human rights abuse problems? Why should Americans legitimize Kim Jong Un’s regime without solving problems of democracy and human rights? Apart from removing the threat of a nuclear strike, the logic fails to present any security, economic, geopolitical incentives for America. Moreover, the elimination of the North Korean threat could rather undermine the justifications for the presence of U.S. and U.N. forces in South Korea at a time where there is bipartisan support to strengthen alliances and keep China’s economic and military growth in check. In short, South Korea has failed to present an argument that could resonate with both “good (altruistic)” and “bad (materialistic)” America.

South Korea’s rationale for normalizing relations with North Korea lack incentives and justification for Americans

South Korea’s rationale for the peace process on the Korean Peninsula does not present a strong case for general Americans. Its logic works for only Koreans. It is a narrative for only Koreans, not universal. While it offers the promise of peace on the Korean Peninsula, it fails to rid the problems of North Korea’s repression of human rights and authoritarian political system. It lacks practicality as well. For most Americans, South Korea’s logic behind the peace process argues for the normalization of relations with North Korea that overlooks its long history of human rights violations and acknowledges the legitimacy of the “evil” North Korean regime. It becomes a weak argument that many people, with the exception of peace activists and intellectuals that support the noble cause of bringing peace in the region, would find it hard to get behind.

Israel and the U.S.: A Role Model of Cultural Amity between South Korean People and Americans

Taking everything into account, one can conclude that Americans see no merit in supporting the peace process. To convince skeptical Americans, we need to expand our reasoning to convey that a denuclearized North Korea, working with South Korea and the U.S., would be more beneficial for America in terms of national security and geopolitics than a nuclear-armed North Korea working with China. Moreover, we need to make efforts to shift gears from arguing for political freedom for North Koreans to advancing human rights and improving the people’s quality of life. Otherwise, the U.S. will continue to show indifference and pose doubts about the peace process even in the Biden era. Furthermore, if we consider the fact that South Korea has spent many years appealing to only President Trump and his cabinet, with the exception of a handful of seminars conducted by think tanks, it becomes clear that our communication strategy has overlooked the 300 million American voters. To make progress on the peace process, our strategies will have to be adjusted to ensure Americans that negotiations will not exonerate the North Korean regime and that they will provide the geopolitical security that materialistic America seeks. Moreover, the scope of our approach should be expanded to communicate not just with America’s core inner circle of power but with the general population to ensure that policy directions will remain constant. In fact, Koreans should examine our foreign policies and communication strategies not just for the peace process but for any issues involving South Korea.

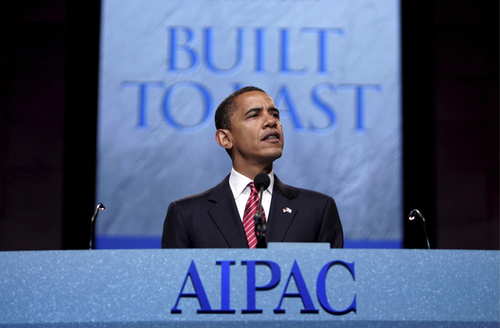

Committee (a pro-Israel lobbying group). AIPAC has a strong influence

in America’s financial, industrial, social circles. (Source: EPA)

Saying “never again” to the Holocaust

America’s sense of duty and historical consciousness

During the campaign for the White House before President Obama was re-elected, one local news channel interviewed an old white woman living in the Midwest. When asked about her pick for the upcoming election, she replied that she was going to vote for the Republican candidate Mitt Romney out of concerns that President Obama would not protect Israel. The interviewee did not have a Jewish background, and neither did her friends or family. What is more, she had never visited Israel. However, she believed that Israel is a country that America should protect. Since President Obama was conducting negotiations with Iran and other Middle East countries, she felt that he was putting Israel at risk instead and was going to vote for Romney. Why would a woman from the Midwest, with no Jewish background and connections with Israel, trouble herself with Israel’s national security? This phenomenon is commonly found in Americans, and it derives from their shared views on Israel, the Holocaust, the world, and their sense of comradery.

The strong emotional ties and the sense of unity that the two countries share were not established by chance. They were not built overnight simply from a movie on the Holocaust or pro-Israel lobby money. After the end of the Second World War, Israel made an all-out effort to build a close relationship with America. Working with Jewish Americans, it fought to instill a sense of duty in Americans that there can be no recurrence of the Holocaust and leveraged this sentiment to build an “artificial” sense of unity and strong historical consciousness.

Israel’s foreign policy strategy goes beyond mobilizing wealthy Jewish Americans to provide lobby money to American politicians. Through a book titled Israel Lobby, Professor John Mearsheimer (University of Chicago) and Professor Stephen Walt (Harvard University) opened the debate on the role and impact of the Jewish lobby on U.S. foreign policy. However, publishers were reluctant to publish the paper due to the vast influence of Jewish organizations. In fact, when the book was published through the London Review of Books, the editor worried about the potential threats he could receive for years for publishing the paper.

Using the exchange of culture and people to facilitate subtle, subliminal integration

Israel’s strategy is much beyond lobbying in Washington, DC. Israel has tried to remember the universal belief “never again” of the Holocaust tragedy by sharing memories and lessons with the American people, including building Holocaust museums in local towns and making movies, documentaries, books and historical textbooks. American students from elementary school to high school visited local Holocaust museums as part of their field trips, and Israel worked to establish relationships with American schools and cities. Israel’s ambassador to the U.S., foreign minister, and prime minister of the Israel government made frequent trips to Washington, D.C. every year to give speeches at the U.S. Congress. They also continued to strengthen their relationships by attending forums and sharing meals with the members of Congress. Moreover, they made frequent appearances on major TV news programs to share Israel’s thoughts and ideas with the American public. In short, Israel not only engaged in lobbying activities with the top-level administration but also made sure to integrate itself into America’s history and life to move the general population. In other words, its national security strategy was to build a sense of unity between the two countries. Their strong bilateral relationship did not occur by chance. It was the result of hard work and strategy.

Japan and Saudi Arabia in Washington DC

Japan is another example. As we look at the cherry blossoms of D.C., the countless number of American scholars that receive scholarship and grants from Japanese foundations, including Sasakawa foundation, and study Japan, and the attention and affection that Japanese culture, like sushi, kimono, movies, comics, and music receives from Americans and Europeans, we cannot continue to sit on our hands and chalk up their success to their wealth.

For decades, Saudi Arabia also invested billions in the U.S. Congress and academics to pass the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) to protect the national security of Saudi Arabia. Every day, legal lobbying groups that represent the common interest of the nation in Congress, fundraisers, publishing events and local events, and ambassadors, journalists, academics, and business leaders work to communicate with others and build networks.

Where does South Korea stand in all this? Regrettably, there is no South Korea in the inner circles of Washington DC. On my part, I often receive invitations from my personal connections to attend events hosted by President Trump, former Republican House Speaker Paul Ryan, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and other key members of the Republican and Democrat party. These invitations are always marked with the question that asks where the Koreans that work to expand the country’s interests are. Diplomacy always starts much before papers are signed in official settings. Negotiations occur at these gatherings, and they lead to results. However, South Korea is nowhere to be found in Washington’s diplomacy circles. It is our reality that South Korea’s interests go unheard in the U.S.

Target Audiences of Korean Public Diplomacy should be expanded and diversified

Until now, South Korea’s communication strategy for the U.S. has been limited to offering academic seminars for the Korean community in the U.S. and a select number of research centers and scholars that study Korea. Much of the audience in such programs, aside from a few students that may have recently gained interest in Seoul, would have been those that are already familiar with Korea, including Korean visiting professors residing in the U.S. as part of their exchange programs, foreign correspondents, first and second-generation Korean immigrants, American soldiers that were dispatched to Korea, diplomats, spouses of Koreans, and Korean exchange students. Of course, there is value in such events. However, the audience that we target consists of people that have already formed their opinions on South Korea and are familiar with its circumstances. Repetitively hosting events that only brings these people together would be an ineffective method of communication. However, South Korea’s strategy remains unchanged, and South Korean ambassadors and foreign ministers host, attend, support, and participate in such events as they have done so for decades. Koreans need to communicate and share value with more Americans.

Media, including TV News Show Programs: For a Better Communication

As a middle power, South Korea should now adopt policies that are on par with Israel and Japan. We must expand the scope of our American friends, even if our budget is limited, and target the masses that are unfamiliar with South Korea. This especially applies to public diplomacy for Korea’s policies. Another effective communication strategy is the appearance of Korean diplomats, scholars, and politicians on American news programs to introduce South Korean policies and agendas. However, such actions are almost unprecedented. Attempts at public engagement were discouraged by a great barrier and further restricted by language and cultural differences. Interviews that discussed Korea’s responses to the recent pandemic with Minister Kyung-Wha Kang and appearances of Korean scholars from American think tanks that have established political opinions are all that has happened over recent years.

Koreans have to continue to expose Americans to our agendas and policies through the most popular news and current affairs programs. Prime ministers, ambassadors, public ministers, and diplomats from Israel, Germany, Saudi Arabia, India, U.K., France, Russia, and other major nations make frequent appearances on these programs to connect with Americans. Likewise, we must develop a strategy to oversee the efforts to ensure journal articles for public relations, such as op-eds written by Korean diplomats and scholars, are published on daily newspapers that intellectuals subscribe to (including liberal papers like the New York Times and Washington Post and conservative papers like the Wall Street Journal) and weekly magazines (including liberal publications like the Nation, the New Republic, and the New Yorker, conservative magazines like Weekly Standard and the National Review, and moderate publications like the Economist, Newsweek, and the Time) and engage in sponsorship activities to encourage the publication of such materials. Regrettably, it is our grim reality that, at times, we tout publications of pieces written by Korean ministers and the president as part of a yearly event on these major news outlets as remarkable achievements. Now, we should strive to facilitate discussions on Korean policies and agendas on a weekly or monthly basis and lead the discourse. We must continue to publicize articles that may even spark controversies to introduce new agendas to the discussion.

Building a shared sense of unity and friendship through the Network of Major Social Clubs

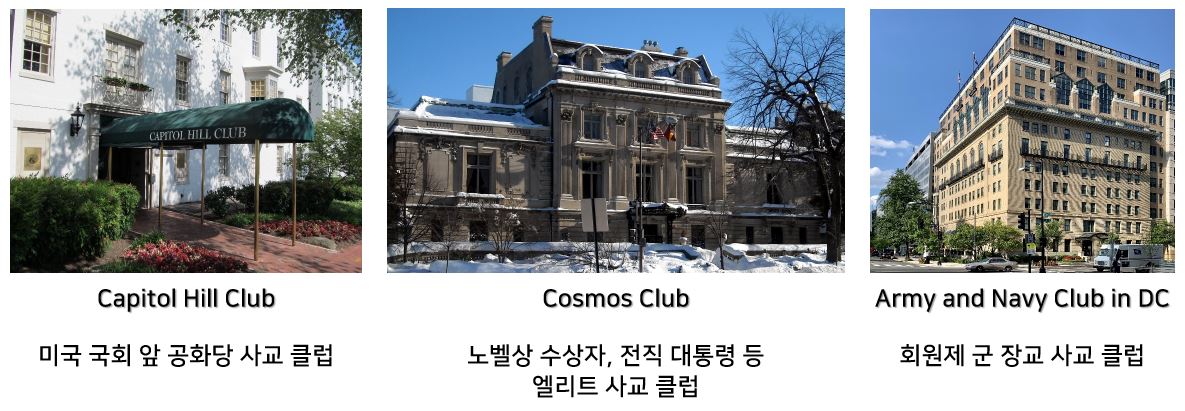

Major social clubs are also important venues of diplomatic negotiation and communication; thus, it is imperative that we ensure that speakers who sympathize with South Korea are a part of these organizations. Like every other country, policy-making and diplomacy in the U.S. begin in private settings, much before the formal negotiation of Track One meetings. China and Russia are not the only countries that value private meals and personal friendship in diplomacy. Personal connections and networks are the first ‘make-or-break’ factors that determine everything in America as well. Their significance goes beyond lobbying, in that they build cultural amity or emotional bonds that encourage people to feel a sense of comradery – that they are on the same side with the same goals. Including the Cosmos club that brings together elites, Capitol Club and political minds, and Army and Navy Club and military generals, there are various types of social clubs in America. Unlike the golf games and drinks at karaoke bars of South Korea, these social clubs host various types of events, including publishing events and fundraisers. In these events that I am often invited to, South Koreans are nowhere to be seen, contrary to the Japanese and Israelis. Like every other nation, every important foreign policy decisions in the U.S. involve not just money, but personal connections and friendships, sharing values and interests that are continuously renewed through meetings in public settings like the White House, the State Department, and the Pentagon and in private gatherings. Policies in the U.S. are developed and shaped by not only national interests and economic gains but also by the interactions between policymakers (lawmakers, public officials, and soldiers) and stakeholders (business leaders, the press, and civic groups). If we confine our thinking to the Hollywood image of the U.S. President that sits in the White House concerned about the state of the country and makes decisions solely based on the reports that they receive, we will not be able to integrate our agendas in America’s policies.

Golf games and pictures will not build bonds of connection

Pursuing mutual benefits and common values

Social interaction between policymakers of South Korea and the U.S. is of the essence. Like Korea, American public offices have career and non-career (appointed, elected) positions. However, leaders in non-career positions in America hold more power than they do in Korea. Members of the Cabinet and the governing party are both the ruling power and top decision-making authority in the U.S. We cannot hope to build emotional ties with these people through short meetings, dinners, and photos. Koreans must work together on mutually beneficial projects and share a common purpose. For instance, in pursuing mid-term projects on North Korea, it becomes much easier to negotiate with the U.S. on North Korea policy if the South Korean government can encourage American senators, representatives, and businesses to get involved in the project. I personally have an experience of speaking with business leaders and policymakers that had an interest in investing in North Korean real estate. One game of golf or one dinner cannot establish friendship and networks between South Korea and the U.S. Moreover, we do not have to limit ourselves to issues related to North Korea when we pursue common interests and build ties with American policymakers. Koreans could, in fact, seek economic gains or share political goals.

The following is a table of House of Representatives that supported the House resolution to declare an end to the Korean War.

the Korean War represent. (List compiled by the author)

For example, though they were motivated to sign the resolution by the grass-root peace movement, representatives from these 19 states sympathize with South Korea and hold the potential of expanding the bilateral network. While it just so happens that all 51 cosponsors are from the Democratic Party, if we work with them and with politicians from regions that are in high demand for local jobs, particularly the Mid-west and the South, on our Green New Deal projects, it could potentially prove to be an effective strategy to strengthen voices for South Korea in Congress.

Representatives who have signed the resolution as of November 29th, 2020 and their constituents are as follows.

Bilateral interactions between local governments, civic groups, and schools through sister partnerships, cultural exchange programs, and essay contests, among others, are of critical importance. Israel, for example, engages not only with elites in the political sphere but with students and local governments through various programs, large and small, to foster cultural amity and bolster their relationship. Considering that South Korea has developed to a point where it can reciprocate America’s economic assistance, Koreans should now seek to expand networks with the U.S. through mutually beneficial engagements, rather than one-sided ones, and support this transition with government funds, legal assistance, and campaigns.

Procuring more pro-Korean voices in America’s political sphere in a way that is not swayed by election outcomes

Koreans have to start thinking about the U.S. not from Koreans’ perspectives but from Americans’. In other words, Koreans should not be content to speak about South Korea to Americans from just Korean perspectives. Koreans must consider what South Korea means to Americans as well. The time has come for South Korea to act as a middle power and apply Americans’ way of thinking to maximize our agendas and strategies. Koreans should do away with the old form of public diplomacy where Koreans compete to portray themselves as America’s closest confidant after each U.S. presidential elections and work to establish a strong presence of Korea’s friends in America’s political circles regardless of the election outcome.

The Republic of Korea – The U.S. Friendship and Cultural Amity Matters

Korea’s friends in positions of U.S. ambassador to South Korea to the Commander of ROK-U.S. Combined Forces Command (CFC), Secretary of State, Assistant Secretary of State for East Asia and Pacific Affairs, National Security Advisor for the White House, and the Chairman of the House and Senate Foreign Relations Committee are an important bridge between the ROK and the U.S. The time has come for South Korea to stop twiddling its thumbs on U.S. elections and hoping for the best. Now, we should become a nation that can get the people we want in the seats that we desire by adopting an advanced nation-style diplomacy that operates on the backbone of a united effort from politicians across the aisles to public and private sector players and experts. Koreans must ensure that South Korea stays relevant in American politics regardless of which party comes to power and elevate our position and our alliance with the U.S. to the levels of Japan and Israel. In summary, Koreans have to usher in an era that unites Koreans and Americans through our shared principles of liberal democracy, market economy, and human rights, along with our ties, comradery, and cultural amity.

|

Young-Jun Kim is an expert on Korean Peninsula security, defense, and military issues. |

This text was originally published on Yeosijae’s Korean homepage on December 2nd, 2020.

< Copyright holder © TAEJAE FUTURE CONSENSUS INSTITUTE, Not available for redistribution >