Please join Yeosijae as we build a brighter future for Korea. Create your account to participate various events organized by Yeosijae.

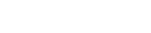

Age of Entanglement: Future of the Cities -A conversation with Oxford University Professor Ian Goldin

*Note: The following article is not a word-for-word quotation of the conversation. It has been organized and paraphrased in a Q&A fashion so that readers could easily grasp the main themes explored throughout the conversation.

Reimagining cities to restore community

We are in the age of hyperconnectivity, where access is unlimited but isolation grows. Community bonds are fraying, and political divisions are growing. Global crises, from the pandemic to climate change, threaten the vulnerable, yet international cooperation is faltering amid great power competition. The pandemic, subsequent wars, and the climate crisis have hit the global economy hard, with the impact disproportionately threatening the survival of developing countries and the most vulnerable in society. Global cooperation is urgently needed, but countries are pulling apart amid US-China competition. Technology holds the promise of solving humanity’s greatest challenges but also risks deepening conflict and division.

What choices should humanity make at the crossroads of prosperity and decline? Taejae Future Consensus Institute spoke with Professor Ian Goldin, founding director of the Oxford Martin School, a multidisciplinary institute focused on solving global problems, and former vice president of the World Bank, to discuss the right choices for humanity’s future. Professor Goldin is a leading authority on globalization. Even before the pandemic, he warned that the world could be vulnerable to pandemics and other dangers, analyzing the risks of our hyperconnected world. In his latest book, Age of the City, he emphasizes the need to build healthy urban networks for sustainable prosperity.

Our Society is More than ‘Connected’; It’s ‘Entangled’

Q. You are in Korea for the World Knowledge Forum, and the title of your talk is ‘From Connectivity to Entanglement’. Why did you choose the word ‘entanglement’?

A. Globalization has interwoven people, goods, and information in ways once unimaginable. It’s no exaggeration to say that everyone on the planet is connected. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown that no one can escape this connection anymore. In fact, many of our modern problems are an example of this. The economic crisis of 2008 was one of them, and so is the climate crisis.

This is where the term “entanglement” comes from. When you are connected, you can choose to disconnect Entanglement, however, is a stronger word, implying that we are all deeply intertwined in a global knot from which no one can untangle alone. While our hyperconnected society has brought great innovation and prosperity to humanity, it has also increased systemic risk. This phenomenon is a defining characteristic of our era.

We Need a ‘Your Problem is My Problem’ Community

Q. In your recent book, Age of the City, you make the interesting observation that the development of civilization requires a new belief system along with technological innovation. Modern society is witnessing dazzling advances in digital technology. What new belief system do we need to add to this to move forward as a civilization?

A. The word “entanglement” as we just discussed implies mutual responsibilities. In our entangled world, individual actions and policy changes ripple globally.

Margaret Thatcher famously said, “There is no such thing as society. There are only individual men and women and families.” I disagree. Individual men and women are only as prosperous as the societies they belong to. Humans are social animals with a fundamental need for connection, a species that empathizes with the feelings of others. Our collective prosperity depends on the solidarity we build.

The belief system that has guided the development of our civilization over the past few decades is capital. Individuals, companies, and nations alike have been driven by a strict logic of capital, which has also fueled technological progress. But despite recent technological breakthroughs, deepening inequality in many parts of the world suggests that this is not sustainable, nor is it desirable for capital alone to determine the direction of technological progress. To effectively respond to another pandemic, another economic crisis, or an impending climate disaster, we need to understand the implications of entanglement and cultivate a sense of community.

Q. You point to the city as a place that can foster a sense of community and address the many crises facing humanity. Why are you focusing on cities in particular? Given the deep inequalities that exist among and within cities, what is the reason to believe that cities could, in fact, fulfill this role?

A. For very practical reasons. More than half of the world’s population already lives in cities, and that number will only increase in the future. Especially in places like Europe and Korea, where the proportion of people living alone is increasing, we need to think about ways to foster communities that could complement the absence of traditional families. The ‘15-minute city’ could be one way. Cities could also play an essential role in solving global challenges. Diverse cities are the perfect place for technological and social innovation.

Future of Cities for Human Flourishing:

15-Minute City and More

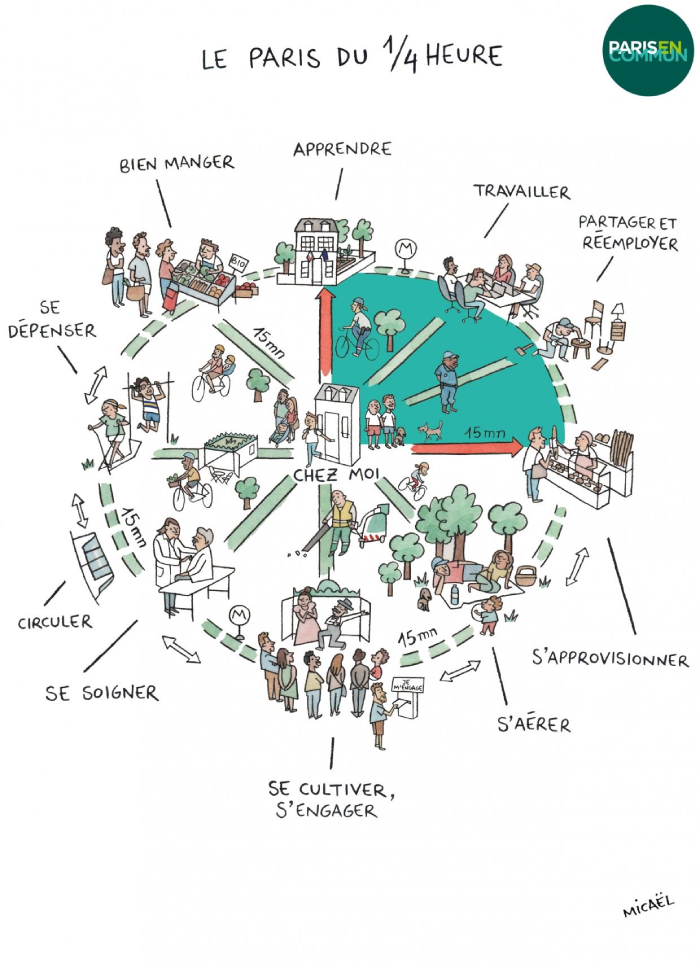

(Source: Paris en Commun)

| The “15-Minute City” is a concept first proposed by the Franco-Colombian urbanist Carlos Moreno during the 2016 Paris Agreement. The idea is to provide citizens with access to the basic functions of life within a radius of 15 minutes by foot, bike, or public transportation. It has been proposed to create intersections where people can interact with each other everywhere, whether it’s living, working, or leisurely space, and to make the city’s infrastructure available for multiple purposes. |

Q. It’s interesting to hear that 15-minute cities could be a way to strengthen the sense of solidarity within society. Does this mean that cities should be reorganized around small towns? Can the concept be applied to large cities like Seoul, London, or New York?

A. A 15-minute city isn’t limited to small towns; it’s about designing neighborhoods where essential services are accessible within a short walk or ride. There is no limit to the size of the city. Large cities like Paris already exemplify this model. Creating hubs where diverse groups live, work, and interact fosters community and reduces carbon emissions. In terms of combating the climate crisis, large cities with good public transportation have much lower carbon emissions per capita than rural areas.

As the global economy has shifted to a knowledge-based economy, the importance of place has changed. It’s less about geography and more about creating spaces where people want to live. If governments prioritize the 15-minute urban design and ensure that every neighborhood has enough spaces for citizens to meet and interact, quality of life and satisfaction will increase, and a sense of solidarity will grow. When you know the faces of your neighbors through frequent interactions in restaurants, on walks, at youth centers, etc., a sense of community is naturally created. You begin to feel that your actions directly affect the area you live in, a fitting attitude in the age of entanglement.

As I mentioned earlier, humans are social animals, so face-to-face experiences have a huge impact on our sense of community. In a similar vein, I’m in favor of blended work arrangements rather than 100% remote work. Newcomers to the workforce need an apprenticeship period to learn the culture of the organization from their peers, which is difficult to achieve when all interactions occur online.

However, there is a prerequisite for 15-minute cities to have the effect I just described: diversity. It’s not beneficial to be divided into zones specialized for certain industries, as some cities are today. If there’s an AI company, there should be a gym next to it as well as a restaurant. It doesn’t make sense if all the residents in that neighborhood are AI company employees while the employees working at the nearby restaurant face a two-hour commute. A 15-minute city should be a 15-minute city for everyone, not just for a specific group of people.

Q. The center of civilization has shifted from cities to empires to modern nation-states. In recent years, the nation-state system has been criticized for its failings; advocates of the charter city movement argue that we should give cities their own governance system as an alternative. What is your opinion on this matter?

A. The current model of multilateral cooperation through the nation-state system or international institutions is not working. The context in which they were invented is markedly different from the context of the 21st century. In many ways, it is true that cities need to show greater leadership in the current frustrating situation. Cooperation between city governments is lighter and easier than cooperation between nations. Especially in times of deteriorating international relations, city networks can effectively address pressing global challenges like pandemics and the climate crisis.

That’s not to say that cities will replace the nation-state system. For one thing, there’s the issue of revenue distribution. This is also why I disagree with the charter city movement. If every city becomes a charter city, it would be returning to a zero-sum game of the ancient city-states. The gap between rich and poor cities will widen; inequalities and competitions will increase. If the national government appropriately distributes tax revenues to each city, we can move toward shared prosperity. What may seem like a short-term disadvantage to citizens of wealthier cities will, in the long run, boost the economy of the country as a whole. In other words, it’s not about bringing the units of civilization back to the cities, but about using the network of cities to fill the gaps in the nation-state system. Councils like the Cities Climate Leadership Group, which was created to respond to the climate crisis, or the Cities Alliance to End Poverty are good examples to this.

Megacities will need to be more proactive in claiming political influence. They need to increase the amount of tax revenue available to city governments, and clarify the division of roles with the central government, which is responsible for defense, universal welfare, and justice.

The Oxford Martin School:

Interdisciplinary Effort to Generate Solutions to Global Problems

(right) The Martin School’s mission to “finding solutions to the world’s most urgent problems.”

| Professor Ian Goldin is the founding director of the Oxford Martin School. With the mission statement of “Finding solutions to the world’s most urgent problems,” the Oxford Martin School was founded in 2005 after James Martin made the largest benefaction to Oxford University in its 900-year history. It is the parent organization of some of the world’s leading research institutes, including the Future of Humanity Institute. We asked Goldin about the role of traditional knowledge institutes in the rapidly changing knowledge ecosystem with the rise of AI. |

Q. The rapid development of artificial intelligence is changing the landscape of traditional knowledge institutions such as universities and think tanks. The Martin School stands out from the crowd. What sets the Martin School apart from other organizations? As the founding director of the Martin School, what do you think is the meaning of a knowledge institution in the modern era?

A. The Martin School is a unique place. It shares the long and storied tradition of Oxford University, but James Martin, our generous benefactor, was a brilliant businessman. While university research institutions are usually characterized by the publication of journals and papers, Martin demanded practical solutions from the start.

As you get more advanced and specialized in your field, you often get stuck in it. If you just skim through the top journals right now, you’ll find that they’re full of jargon that’s hard to understand unless you’re an expert in the field. Real-world problems don’t neatly fit into a single field. Take cancer diagnosis and treatment. Think about how many doctors from different specialties meet for a single patient.

At the Martin School, we have four clear criteria: scale, excellence, impact, and additionality. To start a project, the problem must be of a global scale. The participants must be among the top global academics in the world at addressing the issue at hand, and they must demonstrate how the research will lead to the solution. Lastly, it must be clear how being part of the Oxford Martin School will make the work possible and what it will contribute to the School community. Funding is only available for a minimum of two years and a maximum of 10 years. The idea is to give people enough time to do their research, but to keep the organization flexible and agile. Today, we have more than 30 projects running simultaneously.

A knowledge-producing organization in the digital age shouldn’t be a silo of experts. They need to actively connect with the real world and help find solutions to global problems in a complex, entangled society. Maintaining relevance is key.

The rise of generative AI poses a significant risk of an increase in meaningless information and even disinformation. Think tanks, which are at the forefront of information, need to be particularly proactive in their role of acquiring and discerning quality information.

Despite the Bad, There Are Reasons for Optimism

Q. Today, humanity has achieved unprecedented levels of development. But at the same time, there is a lot of grim news about climate disasters, pandemics, and wars, and there are predictions that the current generation will be the first generation to be less prosperous than previous generations. Do you have any advice or wisdom to share with the youth of the day?

A. It is clear that we are in difficult times. I deeply empathize with the anxiety and despair that young people feel.

The only advice I can give is to take a step back and think about it. Look at the shadows of reality as they are, but don’t overlook the clear progress that is being made. We need to analyze the issues at hand and do what we can.

It is a cumulative process, like drips filling a bathtub. The future doesn’t change because of one or two people but every small effort contributes to a larger transformation. When we understand the shared responsibilities we each have in our entangled world and act our part, suddenly you’ll find the bathtub has a lot more water in it than before. There lie the reasons for optimism.

< Copyright holder © TAEJAE FUTURE CONSENSUS INSTITUTE, Not available for redistribution >