Please join Yeosijae as we build a brighter future for Korea. Create your account to participate various events organized by Yeosijae.

- Insights

- |

- Sustainability

- Future City/Future Housing

[Post-COVID-19 Era / Cities ①] Income Inequality: What makes Swaziland and New York the same

Changing the Course of Our Cities

Since its inception, the Future Consensus Institute (Yeosijae) has focused on “the crisis of urban civilization”, studying different trends, backgrounds, and possible solutions to the crisis. In the past, discussions were primarily focused on the sustainability crisis of large cities and the loss of small towns. An independent session on these issues was even held at the 2019 BOAO Forum for Asia. However, the outbreak of COVID-19 has elevated these issues to the global center stage. We would like to share our findings in four parts, with titles as follows:

- Metropolis in Crisis

- Rediscovering “Local”

- On the Grounds of “Local”

- The Future of Cities: Decentralization

Wuhan, Milano, New York, London,

Daegu and Tokyo

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has reached out far and wide, affecting cities alike, including Wuhan, Milano, New York, London, and closer to home, Daegu in South Korea and Tokyo in Japan. Changes in urban areas brought on by COVID-19 have decorated the headlines of newspapers both domestically and internationally, illustrated in the examples of “COVID-19 Strikes Megalopolis, Urban Civilization in Crisis (Apr. 17. Pressian)” and “Cities after coronavirus: how COVID-19 could radically alter urban life (Mar. 26. Guardian)”. This demonstrates why the United Nations selected sustainable cities as one of the main 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2016.

The world is facing an existential threat from the sustainability crisis. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimates that the climate impacts will displace 410 million people by 2025 in just Asia alone. Once the global temperature rise reaches 2 degrees Celsius compared to the pre-industrialization era, or the CO2 concentration of 450 parts per million, we will have reached the point of no return on the road to destruction. At the current rate of CO2 gains, humanity has just about 12 years remaining until we reach the tipping point. Still, no actions are being taken.

(Source: Yonhap News / Reuters)

91% of OECD’s 275 Cities

At-Risk of Exposure to Fine Particles

Cities account for 71% of energy-related emissions, a major contributor to CO2 emissions. Less than 1% of 13,000 cities across 189 nations (or just one hundred metropolises) release 18% of the global greenhouse gas emissions. The primary source of air pollution is urban transportation, with air pollution causing 7 million deaths just in 2018 alone. 91% of the 275 cities in OECD countries are at risk of exposure to particulate matter (exceeding the WHO guideline on annual average PM 2.5 concentration of 10μg/m³), with growing cities in emerging countries faring much worse. Delhi (India) recorded PM10 levels 10 times the WHO annual mean guideline of 20μg/m³, followed by Cairo (Egypt) and Dhaka (Bangladesh) with 7 times, and Beijing (China) and Mumbai and Calcutta (India) with 5 times the standard (2018 WHO data).

New York’s 1% Hauls in More than

Forty Times the Average Income of the Bottom 99%

Climate and air pollution are not the only problems of our cities. City dwellers are also faced with unsustainable social conditions. Inequality in metropolitan areas of advanced states rival those in countries deemed to be the most unequal. New York, where the income of the top 1 percent outstrips the bottom 99 percent by 40 folds, has a Gini coefficient of 0.504, similar to the levels of Swaziland. L.A. (0.496) hovers just below Sri Lanka (0.490), whereas Boston (0.469) is slightly above Rwanda (0.468). In London, the top 10 percent possess 295 times the wealth of the lower 10 percent. Seoul (0.336 as of 2017, the Seoul Institute) placed above Mongol (0.327) and Albania (0.332) (World Bank data). In comparison with small-sized cities and rural areas, the relative poverty rate in metropolitan areas was significantly higher with greater increases. The number of people in poverty in the largest cities of the U.S. has increased by twofold between 1970 and 2015, from 15 million people to almost 30 million. However, the rates in rural areas have remained static, maintaining the same level of 8 million people since the 1970s.

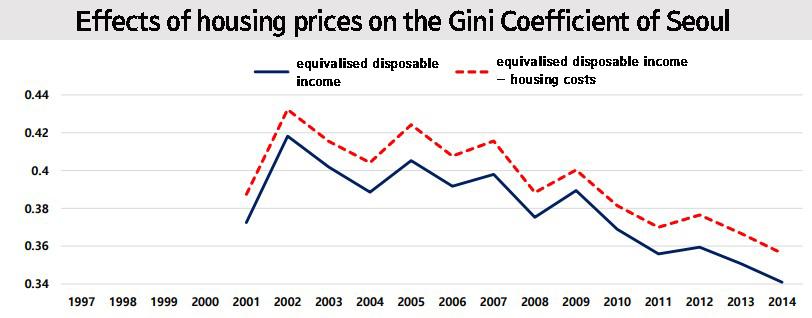

Higher living expenses, namely the cost of living, are the main sources of income inequality. According to the Seoul Institute, income inequality in Seoul increased from 2008, despite increases in the overall wage and salary income. This is because the burden of housing cost is heaviest for low-income households. When housing costs were deducted from the disposable income of households in Seoul, the gap grew even wider.

Having to Work Fingers to the Bone

To Pay Off Mortgage Loans

The same trend can be observed in other metropolises throughout the world, with housing expenditures ranging from 30 percent (Boston) to 120 percent (Beijing) of net income. Housing costs in Beijing have been driven up by people flooding into the capital due to worsening economic conditions in nearby regions, while much of the land has been allocated to the state and state-owned businesses. As a result, many people, with exceptions to high-income households, are being driven out to the outskirts of the city. The best performing cities and provinces of China, specifically Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Zhejiang, were amongst the lowest in the happiness index due to spikes in housing prices. In 2010, when the Chinese economy was rapidly expanding, the first happiness index in China for the middle class, the “White Book of Happiness of Middle-Class Families”, was released. Many households surveyed in the report felt unhappy about the increasing pressure of mortgage loans and having to work longer hours to make ends meet. The price of homes in Silicon Valley is four times the national average, explaining why the net inflow of people has shrunk from 19,511 in 2012 to 308 in 2017.

Metropolitans also suffer from the loss of time due to congestion. For commuters polled by Ford Germany, commuting to work was more stressful than a dentist appointment. Inequalities and stresses in urban environments have turned depression into the world’s largest health problem (contributing 15 percent of the total burden of disease, WHO 2016). With one out of ten people suffering from depression committing suicide, large cities are threatening not only nature but the lives of humans as well.

As a result, people have become eager to ditch their lives in cities. In fact, a growing number of people are fleeing from the cities. According to a survey conducted in 2011 by the job posting site JOBKOREA, almost 8 out of 10 workers living in cities (or 78.4 percent of respondents) have considered “moving out of cities”. Rural rebound has steadily increased since it was first surveyed in 2013, reaching 500,000 turnarounds in 2017. Hundreds of workers are now leaving cities in the U.S. daily, including those from New York (277), LA (201), and Chicago (161) in 2018.

Unsustainable Large Cities

Vanishing Small/Medium-Sized Cities

However, the living conditions of rural areas and small towns are also on the decline. Overshadowed by the growth of metropolises, other regions have seen their risks of poverty and unemployment increase, while the lack of access to infrastructure has gotten worse. Poverty rates in rural U.S. are 1.5 times higher while there are 8%p fewer job gains and 35%p fewer broadband infrastructure compared to the urban U.S. These figures show that small cities have almost stopped functioning as a growth engine for the American economy. In the early 90s, 125 counties combined generated half of the job gains in the U.S., whereas in 2010, just 20 counties – counties with major cities such as New York and San Francisco – generated half the growth.

Megacities to Increase

From 28 in 2014 to 43 in 2030

Half of local districts and counties in Japan will disappear by 2040 (Masuda Report 2014), whereas a third of the 228 local municipalities in South Korea will vanish in the next 30 years (Korea Employment Information Service 2017). In China, 80 of the small and medium-sized cities have experienced a sharp decline in population between 2007 and 2016. Even Europe, a relatively well-balanced region, is suffering from the same problem. In the case of Germany, the population has been on the decline for 59 of the 107 urban districts due to a high concentration of young people in big cities.

Despite the adverse effects, cities throughout the world are still expanding. Urbanization, which was estimated to be around 55 percent in 2019, is projected to reach 60 percent by 2030 and the number of megacities (cities with a population over ten million) will rise from 33 in 2018 to 43 in 2030 (UN 2018). In other words, the sustainability crisis that looms over the human and natural world will worsen, with less and less time remaining to take preemptive measures against an ecological breakdown.

COVID-19: A Wake-Up Call and the Last Warning from Nature

For the Humankind to Mend Its Ways

COVID-19 could potentially be a wake-up call and the last warning from nature for humans to address the problems of our megacities. Immediately after cities came to a halt due to the coronavirus, pollution was cleared from the skies and animals reclaimed their lands. The virus had achieved what the Paris Agreement could not do. The old joke that nature will strike back to protect Earth from humans seems to be as valid as ever, and this will hardly be the last of the attacks.

From the Plague of Athens in the 5th century BC to the Black Death in the Middle Ages and the cholera outbreak in 19th century London, epidemics have always laid bare the contradictions of our cities and prompted innovation. The current pandemic could also be a golden opportunity to address the unsustainable environments of cities today.

Going Against the Principle of Cities

With Social Distancing

The global pandemic offers a clear, simple message—to stop living in clusters. Advanced water and sewage systems and scientific disease control frameworks that have been fortified over the course of centuries were breached by the novel coronavirus. Social distancing is currently our only means of pushing back against COVID-19. Some cities have flattered themselves for their responses to the crisis, but their remarks overlook the fact that their success was on the account of distancing – which ironically, goes against the “tight-knit” nature of megacities. These cities, as they boast their successes, may just be on their last legs—moments away from falling apart. Once distancing measures ease, the number of new cases could surge again.

Bringing the Fourth Industrial Revolution

Into Our Lives

COVID-19 presents the world with a challenge to disperse the concentrated population, or in other words, to decentralize our cities. Whether it is in the form of multi-centered cities, a complete dismantlement of urban areas, or the establishment of a new network with smaller cities, the urban environment needs to be fundamentally reshaped. Cities today are a result of the Industrial Revolution that took place in the 19th century. Centralization and economies of scale were the core values of the Industrial Revolution, and the same values have created the sustainability crisis that we are facing today. The concentration of population has caused air pollution and stress from traffic congestion and created inequality by driving up housing prices. The Fourth Industrial Revolution (or the Digital Transformation), on the other hand, is grounded on the principles of decentralization, emphasizing quality over quantity. Innovation in cities will be driven by this principle, and for South Korea to maintain the global leadership that it has gained from its response to COVID-19, it will have to take the initiative in innovating the urban environment. Though COVID-19 may be the biggest threat faced by humanity, it could be the perfect chance for South Korea to establish a firm leadership in the global community.

ⅰ Biggest U.S. cities losing hundreds of workers every day, and even more should be fleeing. CNBC. 2019.10.16.

ⅱ The World’s Cities in 2018. UN Data Booklet. (April 6, 2022, Last search date)

This text was originally published on Yeosijae’s Korean homepage on May 24th, 2020.

< Copyright holder © TAEJAE FUTURE CONSENSUS INSTITUTE, Not available for redistribution >