Please join Yeosijae as we build a brighter future for Korea. Create your account to participate various events organized by Yeosijae.

- Insights

- |

- Next-Generation Values

The end of labor unions… Reforming the labor law

Professor Ji-Soon Park discusses why South Korea’s labor laws are losing relevance in today’s world.

The dual shock of the digital industrial revolution and the COVID-19 pandemic has presented an unprecedented set of challenges for the world. While responses are currently focused on pandemic control and disaster relief measures, once the storm is over, we will soon discover that the ground has shifted beneath us—especially in the realm of labor. This will not only impact the employer-employee relationship and insurance but also challenge the social institutions around labor. In this context, the Future Consensus Institute (Yeosijae) invited Ji-Soon Park, a labor law expert and a professor at the Korea University Law School, to conduct a seminar on the Korean labor laws. During the session, Professor Park said, “working hours and working conditions are being redefined today,” and argued “South Korea will need to leverage this opportunity to make major reforms to its labor laws.”

[Summary of Presentation]

1. Why do we need to reform our labor laws?

Reforming the Outdated Labor Laws

One of the most significant unintended consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic is the acceleration of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, primarily through what is called “non-contact” industries. This, of course, has implications for the labor market, just as the previous Industrial Revolutions have done so in the past. The First Industrial Revolution automated labor work, established labor laws, and reduced work hours. The Second Industrial Revolution, on the other hand, ushered in what we call ‘Labor 2.0’, enabling mass production and mass employment while introducing labor unions and collective agreements. ‘Labor 3.0’ began after the 1970s with the Third Industrial Revolution, when the internet distribution began in the Western world. With the arrival of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, boundaries around workplace environments and working hours are changing, and the number of platform workers is increasing exponentially. However, our labor laws remain unchanged. They are still designed around conventional working conditions where workers come to work by 9, have lunch at 12, and leave by 6, and are compensated for any overtime worked on evenings, weekends or holidays. Such outdated laws are unfit for the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

While some startups are showing a strong performance, there are far more that are not faring well. Furthermore, when employers are unable to dismiss employees, a disastrous cycle of conflict emerges and is left unresolved, as employers are required to reinstate any employees that have been terminated unlawfully. This is why reforms should allow more room for employers to let go of their employees, through options such as financial compensations for laid-off employees. Needless to say, this will require legislators to set clear guidelines on fair dismissals.

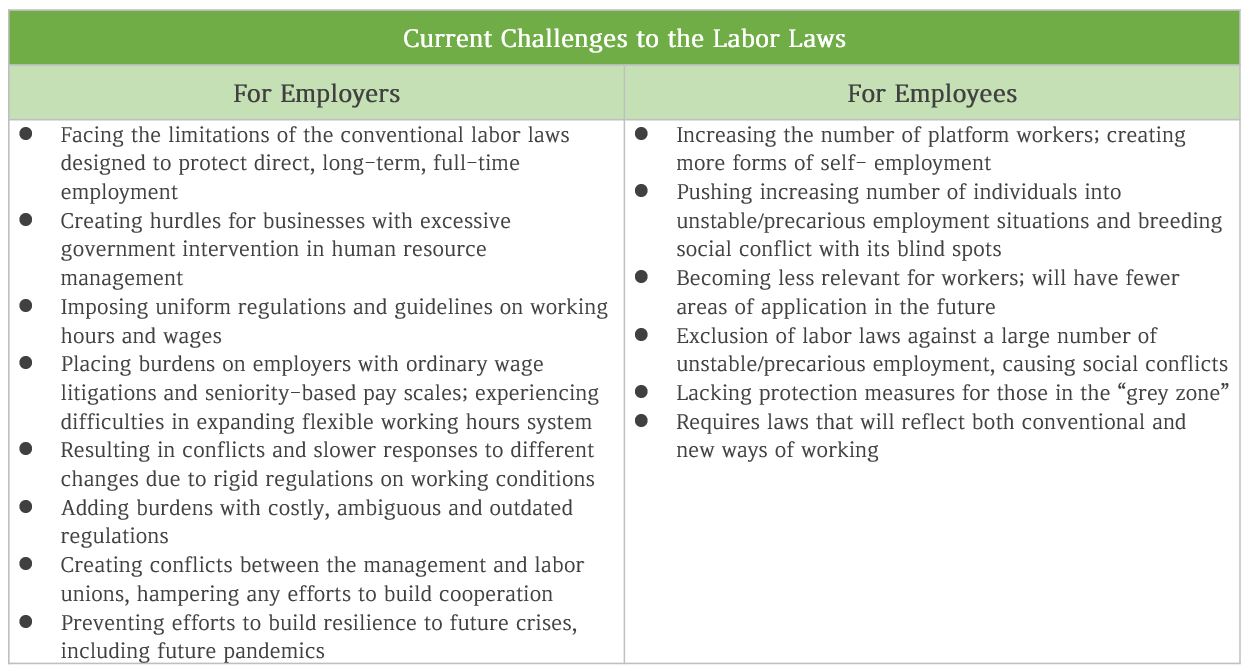

What Outdated Laws Mean for Employers and Employees

The Korean labor laws can be discussed in two perspectives—the employer’s and the employee’s.

For employers, the current law involves excessive government intervention particularly in human resources management. Employers in Korea are especially burdened with the government’s one-size-fits-all approach to wages and working time regulations. For example, litigations on ordinary wages are unique to South Korea and serve to benefit only the law firms by providing a market with a size of seven to eight trillion won per year. South Korea is also the only country out of the G20 countries to have maintained the seniority-based pay scale system, ever since Japan updated its laws in the 1960s. Flexible work arrangements are out of the question due to resistance from the unions. While the circumstances around work continue to change, labor laws prevent the management and labor unions from resolving conflicts on their own, pushing the two parties to settle their matters in court.

For employees, the labor law leaves blind spots for non-traditional employment workers. For example, platform workers are classified as self-employed individuals, leaving them vulnerable without any protection measures to fall back on. Though the law was originally built around blue-collared workers and traditional industries, manufacturing accounts for only 20% of employment today. With fewer areas of application, this outdated system will soon lose its place in the Korean legislative system and will have to be displayed in museums instead.

[How and What to Reform]

Reforms Will Have to…

As illustrated above, changes in the labor market have brought forth a “crisis” of labor law in South Korea. The question to ask now is, what reforms will the Korean government have to make to resolve this crisis? I believe that the government should strive to establish a multilayered system that can capture both the traditional and the new economy.

First, reforms should modernize the labor laws to reflect the new industrial environment. Ambiguous, impractical legislation will have to be changed, and the government will be required to propose innovative laws to replace outdated regulations on working conditions and hours. This will enable a flexible working hours system in particular, by expanding discretionary use of time through expanded rights on working time and the work-week cap system. Europe has been using a working time accounts system since the 1990s. Germany, for example, has a system called “trust-based working hours (Vertrauensarbeitszeit)”, which requires employers and employees to place mutual trust in each other to fulfill their required duties.

Cf. Working Time Accounts

Used to keep track of credits and debits of working hours of individual employees over a certain period of time, allowing flexible hours of work. For example, an employee can choose to work 2 hours in overtime on a certain day to rest in another day. This system was first introduced in Germany and is now used throughout Europe in various forms.

Expanding the Scope

Beyond the Dichotomous “All or Nothing” Approach

Second, reforms should create multilayered legislation that can take into account various forms of employment. Currently, South Korea uses a dichotomous ‘all-or-nothing’ approach in labor law; employees that fall within the boundaries of the law are entitled to rights and benefits as described in the Labor Standards Act, from employment to retirement, including the shared burden of pension insurance contributions with the employer. Others, however, will not receive any benefits or protections from the system. This clearly shows that there are limitations to the conventional one-size-fits-all approach.

Highly compensated employees that are paid over $100,000 per year are exempt from the Fair Labor Standard Act in the U.S., and employees working in the financial field with an annual compensation level of 10 million yen or more are not subject to statutory working hours in Japan. South Korea, on the other hand, requires overtime compensations for all employees, regardless of their wages. Taking this into account, reforms to the labor law should reduce overtime benefits and lend more strength to self-employed individuals and platform workers instead.

Discussions about expanding the labor laws to cover the grey zones of workers (e.g., self-employed individuals and platform workers) have begun in Europe and the U.S., and European countries, including Germany, UK, Italy, and Spain have already established legislative models for non-standard forms of employment. With a late start on reforms, South Korea must recognize the urgency in widening the range of exceptions to the labor law, and implement measures to diversify the system, including legislation to protect the self-employed without employees in a situation of economic dependence and frameworks that ensure fair contract conditions for platform workers.

Emergency relief funds to ride out the COVID-19 outbreak will top 100 trillion won with the first, second, and third supplementary budgets and others that will follow. These stimulus packages come at a price and will have to be collected in the future. This implies that reforming the labor law is no longer an option—it is a must.

From an Updated Version of the Factory Acts

To a New Law

Third, a discussion is needed to enact a Labor Contract Framework Act. In view of the fact that the current framework for employment in Korea (otherwise known as Labor Standards Act) is a modernized version of the Factory Acts from the nineteenth century, the government will have to draft new laws that encompass new ways of working. What this age demands now, is an innovative framework that shifts the responsibility of contract compliance to individuals by allowing them to use their discretion, instead of using government control, surveillance and penalties.

Empowering the Management and the Union

Fourth, new policies should establish collective labor relations to strengthen the autonomy of labor and management. Changes in industries and employment will inevitably weaken the role of unions in the future, and this creates the need to overhaul the labor-management relations to encourage more individual participation. In other words, the new system will have to increase employee representation on industrial and organization levels by using a dual structure approach that encourages industrial unions on one side and works council on the other.

Increasing Preparedness for National Crises

Lastly, new labor laws should be resilient to national emergencies like a pandemic. They should grant legislators the ability to make further reforms to assist economic recovery and facilitate labor-management agreements, including temporary deregulation, to ensure swift responses to crises. Other possible policies include emergency support measures for business and employment stability, temporary easing of regulations on working hours, and policy reforms to encourage remote work.

South Korea’s labor laws, for the past 60 years, have based their policies on the industrialization era context. However, structural changes in our society, economy, and environment—notably the digitization of labor—have transformed how we work. Moreover, with increasing uncertainty due to COVID-19, labor law reforms will become more important to mitigate the crisis’s effects.

2. Case Studies – Germany and the Netherlands

Germany and the COVID-19 Relief Act

Legislators will have to recognize that labor laws, along with information- and competition-related laws, are normative infrastructures for stakeholders and new corporate organizations to manage their reasonable profit in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. From this perspective, it is also imperative to devise new labor laws and consider drafting temporary measures to respond to the challenges posed by the novel coronavirus.

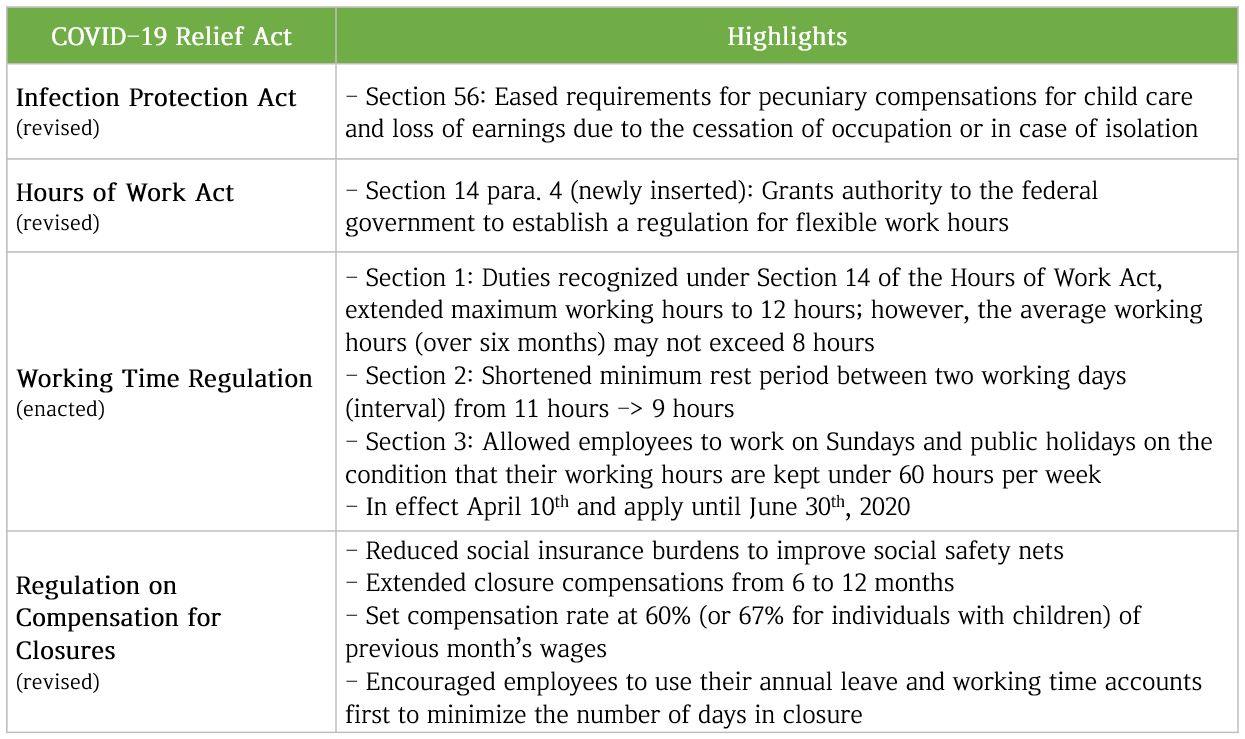

Currently, there are ongoing efforts throughout the world to bridge the gap between law and reality. Germany, in particular, is spearheading this initiative, approving a set of stimulus packages on March 27th to mitigate the effects of COVID-19. The major components of the coronavirus package are as follows:

The Netherlands and Remote Work

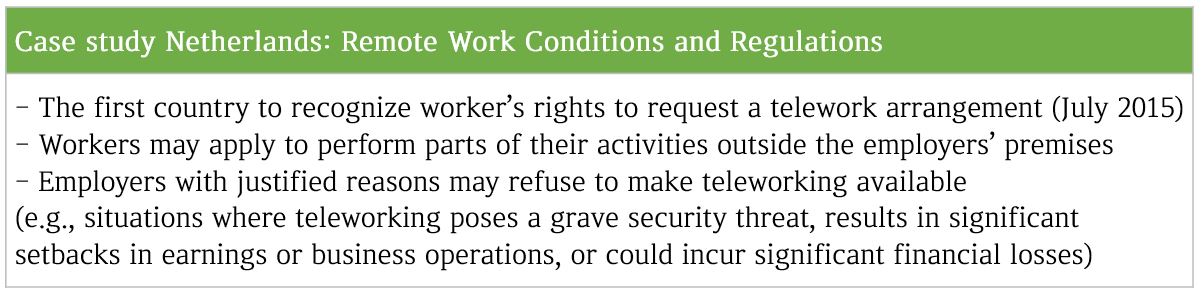

Germany is also drafting legislation on remote work, as it currently remains as an option for employers to consider with no legal entitlement for employees as of yet. The new law is scheduled to be rolled out by the second half of 2020 and aims to strengthen working-time autonomy for employees while protecting the employers’ rights to refuse on justifiable grounds. This legislation, using the 2015 Dutch law on teleworking as a reference, will serve both the employer’s and the employee’s needs by ensuring business profit while making considerations for workers.

3. Challenges Ahead

Moderates and Radicals of UBI

For the past 60 years, labor laws—with its three cores of government monitoring, control, and penalties— have served as the backbone of South Korea’s economic growth. However, this changed over time, with the emergence of social safety nets and labor unions for regular workers. The socio-economic landscape of work is changing, and discussing whether to amend or discard existing laws to adapt to these changes will only hamper progress by politicizing the debate. For this reason, South Korea will have to make a fresh start by devising a new set of laws. And though details are yet to be outlined, discussions have started amongst labor law experts to start the initiative.

Policy debates in the second half of this year will also feature the topics of universal basic income (UBI) and employment insurance for all citizens. Just until recently, advocates for basic income were perceived as radical reformists. However, with the pandemic, perceptions of UBI have completely changed, resulting in a spectrum of basic income variations. On one side are the UBI moderates that support cash allowances for all citizens, to avoid incurring additional costs for the welfare system. On the other side are the UBI radicals that support implementing UBI on top of the existing social welfare programs.

Needless to say, welfare policies should ensure a dignified life for all, and we have to continue to make progress by building on existing foundations for the future generation.

In this context, I would like to propose a hybrid model of UBI for South Korea. First and foremost, implementing radical versions of UBI will be met with stiff resistance from conservative individuals. It will take time to grow a consensus on the UBI system. Moreover, changing the welfare system is a costly procedure for the government. Consequently, it will be imperative that we take the time to collect the necessary data to set ourselves on the right path to success.

Eliminating the Blind Spots of Employment Insurance

Another topic worth mentioning is the employment insurance program. South Korea currently has 20 million wage-earners and 7 million self-employed individuals and freelancers. Out of the 27 million workforces, only 49 percent of workers (or roughly 13.5 million) are covered by the employment insurance, implying that half of the workforce is without jobseeker’s allowance, employment retention subsidies, and vocational training allowances. Furthermore, persons in special forms of employment, non-regular workers and part-timers are now in a blind spot of the employment insurance system. Crises, like the pandemic, serve to widen the gap in benefits, and for these reasons, the government has to eliminate the blind spots in the program.

Under the current policy that emphasizes “low pressure, low payout”, employers and employees are each required to make 0.8 percent contributions to the unemployment insurance. I believe that we have to transition into a “medium pressure, medium payout” system, not just for unemployment but also for pension and national health insurance schemes.

In conclusion, South Koreans will have to engage in a discussion on the overall labor and welfare systems to come to a social consensus. Labor laws, in particular, will have to be the core issue of the debate.

This text was originally published on Yeosijae’s Korean homepage on July 7th, 2020.

< Copyright holder © TAEJAE FUTURE CONSENSUS INSTITUTE, Not available for redistribution >