Please join Yeosijae as we build a brighter future for Korea. Create your account to participate various events organized by Yeosijae.

- Insights

- |

- Global Order and Cooperation

Will South Korea become “the world’s factory” for advanced industries?

We need to move from ‘reshoring only’ to the ‘optimal relocation strategy’.

|

Byoung-Jo Chun graduated from the Department of Economics at Seoul National University and received his Ph.D. in economics at the University of Iowa. He was an economic advisor, an economist at the Asian Development Bank (ADB), and the president of KB Securities. He currently is a Distinguished Fellow at the Future Consensus Institute (Yeosijae). |

The smart factory operates on an automated management system,

from production to packaging and shipment. (Source: Hankyung Magazine)

Factories halt operations

due to the lack of parts

Ever since the pandemic began, there has been a growing interest in reshoring companies. The South Korean government has also named reshoring as one of the main pillars of post-Corona policies.

The emphasis on reshoring is a result of the changes in the international trade environment that had begun in the pre-pandemic era and have since taken more extreme forms. At the heart of the change, is the structure of international trade. Heavy reliance on China in global trade is considered to have increased the risks in the global supply chain.

As a nation that is heavily dependent on China, South Korea also had to bear the brunt of the shock, on top of the losses from the U.S.-China trade conflict. To make matters worse, the spread of COVID-19 halted not only trade but also production. Some manufacturers even had to put production on hold due to disruptions in the supply chain for simple, inexpensive parts.

Successful response to COVID-19 without lockdown,

Increased K-Brand value

COVID-19 has led to positive developments as well. For companies both home and abroad, South Korea’s success with the coronavirus demonstrated the nation’s potential as the alternative global manufacturing center. South Korean companies are once again discussing reshoring as a possible move. Production in South Korea resumed much earlier than other countries, as it controlled its coronavirus outbreak without a nationwide lockdown. Automotive production lines returned to normal as early as early February. Countries and companies that have been struck with a heavy blow by production shutdowns in China turned to South Korea as a possible production base. The ‘shutdown risk’ that has been exposed in the ‘world’s factory’, on top of the decline in the economic incentive to keep production in low-waged areas such as China and Southeast Asia, was enough to convince companies to seek out alternatives.

The coronavirus blame-game has led to an escalation of the U.S.-China trade war. The United States openly called out to its businesses to pull out of China, made exuberant promises of supportive policies,¹ and started mentioning other allies—including South Korea— as alternative sites of production.² This even led to the emergence of a rather rash optimism, that South Korea could become the “world’s factory for advanced industries”.³

¹ On Feb. 2020, the U.S. government announced a policy that will cover the total cost of relocation for reshoring businesses.

² On Apr. 29th, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo mentioned that “the U.S. government is working together with Australia, India, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea, and Vietnam to move the global economy forward.”

³ Professor Jean-Paul Rodrigue of Hofstra University, N.Y. Source: [Korea JoongAng Daily] “South Korea to become ‘the world’s factory for advanced products’.” Apr.20.2020.

Increased recognition of K-brand value has become another reason for Korean businesses to return home. Disease control has now been added to the list of services or goods associated with Korea, with even the Korean model of economy garnering attention as well. This trend is significant in that it plays an important role in where companies choose to manufacture their goods. If products “Made in Korea” are more profitable than products made in other countries, companies might find that the benefits of manufacturing in South Korea outweigh the potential losses that may occur in production costs. Products are often said to be judged not by their price tags, but the values they hold. For South Korean companies that have struggled to expand into different markets despite having an array of quality products, the recognition of K-brand value will certainly be excellent news.

located in Pyeongtaek, Gyeonggi Province (Source: LG Electronics)

Is it time to charge Korean Premium?

Don’t count your chickens before they’ve hatched

However, it is too soon to be counting our chickens. The decision to reshore production cannot be made without a sufficient number of reasons. Relocating production is by no means simple, and the fate of the company could hang on the decision. In fact, there are a host of considerations that companies take into account in determining the optimal location for production.

Smart technologies are

increasing the number of reshoring cases

in U.S. & Germany

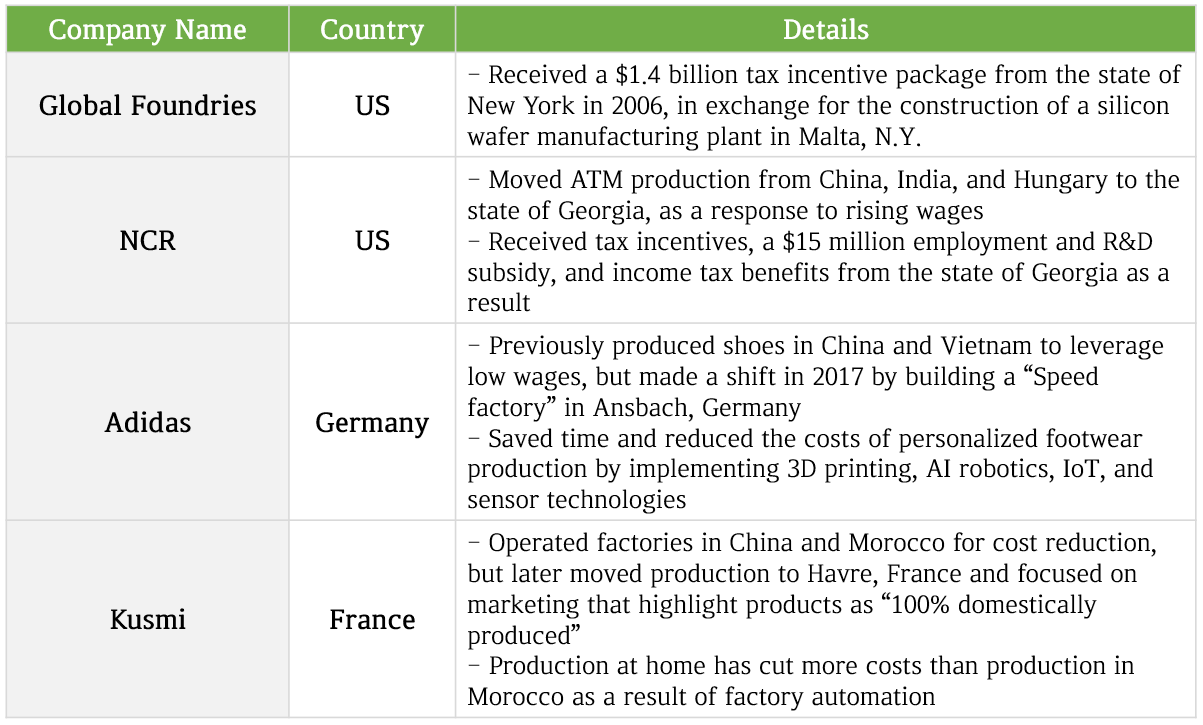

New factors have emerged in the discussion for reshoring: the technologies of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and the penetration of these technologies. Smart manufacturing (or smart factories) are enabling companies to dramatically increase productivity and cut down on production costs by leveraging intelligent information technology (IIT). The implementation of smart manufacturing could accelerate reshoring once the benefits of smart manufacturing outweigh the benefits of overseas production (i.e. low wages, market access, etc.)

In the U.S. and Germany, an increasing number of companies are choosing to reshore their production [Figure 3]. While rising wages in developing states certainly have had an impact, the implementation of smart manufacturing technologies is considered to be the main driver of reshoring. Consequently, smart manufacturing technologies have become an important factor in developing policies, as they increase the chances of reshoring.

Korea:

15 Years of Reshoring Policies

with little to show

Reshoring policies are, in fact, not entirely new in South Korea. Reshoring policies were first introduced in government programs in 2006, as part of the “Comprehensive Plan for the Improvement of the Business Environment”⁴ presented by the Ministry of Finance and Economy. The plan described a comprehensive program of deregulation, which included a ‘U-turn policy’ to support returning companies. Rather than providing direct support for returning companies, the policy intended on improving the overall regulatory environment to facilitate corporate investment and encourage Korean companies to make a U-turn. Reshoring policies have been expanded over the course of years by previous administrations⁵, but the results were disappointing.⁶

⁴ The Ministry of Finance and Economy. Sep. 2006. Refer to the press release on the “Comprehensive Plan for the Improvement of the Business Environment”. The plan outlined incentives designed to attract investment in the era of a new international division of labor and to lure companies back to Korea.

⁵ Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Energy. Nov. 29. 2018. “Comprehensive Plan for U-turn Companies”.

⁶ Since 2014, only 69 businesses have returned to Korea. By year: 20 (2014), 3 (2015), 12 (2016), 4 (2017), 9 (2018), and 5 (as of Apr. 2020).

The motivations in moving manufacturing offshore offers insights as to why only a few companies are choosing to return to South Korea. Key drivers of production relocation for Korean companies were expanding business into foreign markets and boosting exports. Majority of Korean companies expanded into foreign markets by positioning themselves in nearby countries, or by ‘nearshoring’ business.⁷ On the other hand, low wages served as a motivation for only 7% of Korean companies, which implies a limited pool of companies that stands to benefit from reshoring policies.

⁷The Export-Import Bank of Korea looked into why companies invest abroad for the past 5 years, and the results were: expansion into foreign markets (71%), promoting exports (13%), and leveraging low wages (7%).

Low wages account for

only 7% of production relocation

Of course this should not suggest that reshoring is ineffective. Efforts to mitigate the risk of production shutdowns while making full use of the new environment that has been created on the backdrop of the U.S.-China trade conflict and COVID-19, was what sparked the discussion on reshoring. In other words, reshoring could mitigate the risk related to the re-concentration of manufacturing and uncertainties of the new trade environment (i.e. U.S.-China trade conflict, dwindling sentiment towards free trade) while seizing new positive opportunities that have appeared.

However, making use of opportunities and challenges will require a policy that goes beyond the limitations of reshoring, to take into consideration an array of production sites. A ‘reshoring only’ approach would only focus on bringing manufacturing back home, but an ideal approach would be a comprehensive approach that also incorporates “near-shoring”, from partial reshoring of factories to relocation of plants to a third country for optimal production relocation.

Optimal production relocation

should leverage FTAs

Taking the discourse of reshoring into the context of optimal relocation of production, there is a clear direction in which policies should take.

The first is risk management. Concentrating production in one region is becoming increasingly risky, therefore, a second method, where manufacturing is split between on- and off-shore sites, must be examined. There are various ways to streamline production, with shutting down offshore factories and making new investments in South Korea or a third country as an example. What maintains companies’ access to different markets while enabling production relocation is the Free Trade Agreement (FTA). Under an FTA, companies are given unhindered access to other markets (e.g. China)—though complications such as a lack of a supply chain for a component or an increase in logistic costs may arise. For example, the ASEAN-China FTA enables companies to make expansion investments in ASEAN nations and mitigate risk, while maintaining access to the Chinese market. Likewise, the Korea-China FTA allows companies to consider Korea as a possible production site. Consequently, ‘partial U-turns’ should also be incorporated in our policies, and making sure that these aspects are not overlooked will prove to be important.

Restructuring the trade network

around the U.S.

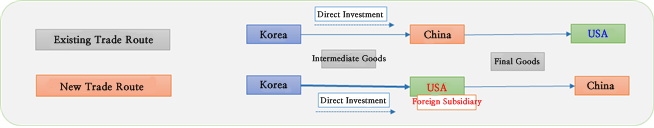

The second involves a strategy that takes advantage of risks and opportunities that emerged from the U.S.-China trade conflict. The trade diversion⁸ following the U.S.-China trade agreement foreshadows a drop in Korea’s exports to China. A way to respond to these changes is to partially or entirely move production to the U.S. In the past, South Korean businesses that have expanded to China imported intermediate goods from Korea to manufacture the finished goods and export them to the U.S. With the shift, Korean companies will have to expand to the U.S. by setting up a foreign subsidiary, import intermediate goods from South Korea, and produce China-bound products. This means that a new global trade network, centered around the U.S., will appear. Under the new trade network, South Korea will be able to maintain the exports of intermediate goods and increase overall profitability, once the trade network to China has been established. If future U.S.-China negotiation developments favor the U.S., it may even lead to an increase in exports of intermediate goods [Image]. Ultimately, the efforts to mitigate the risks of the U.S.-China trade conflict will lead to a partial or full-scale relocation of plants from China to the U.S.

⁸ China agreed to purchase $200 billion worth of goods from the U.S. as part of the U.S.-China “phase one” trade deal; South Korea’s exports are expected to decline as a result.

Encouraging strategic manufacturing to ensure

a minimum level of production for core, security-related essential products

The third and last is maintaining a minimum level of production capacity in South Korea. Lessons to take from the U.S.-China trade conflict and the threat of COVID-19 is that a minimum level of manufacturing has to be in place to mitigate risks for companies. This naturally applies to key industries and essential products, especially the materials, parts, and equipment sectors. Many advanced nations are now experiencing first-hand the detrimental effects of heavy reliance on China, with no national capacity to produce basic medical supplies and equipment to fall back on. Maintaining a level of production capacity, in other words, is not a matter of efficiency, but a matter of security. Companies insufficiently prepared in this regard are expected to build their domestic production capacity in the future. However, these investments are indistinguishable from conventional investments, making it difficult to benefit from reshoring initiatives. For this reason, the government has to come up with supportive measures that will assist strategic manufacturing.

Effective optimal relocation strategy

will create domestic jobs even as companies

head offshore

Another reason why there are strong advocates for reshoring initiatives is because of domestic job creation. The U.S. administration has been stressing the importance of reshoring on job creation, and the same argument can be found in South Korea. However, there is a discrepancy between expectations and reality. The relationship between job creation and reshoring – or even offshoring – has not been established. This means offshore production could potentially lead to more jobs, while onshore production –in contrast – could destroy jobs. Whether it be on- or off-shore production, production has to increase domestic investments to create jobs at home. In other words, the employment rate could increase even as companies take manufacturing offshore, if investments and exports of intermediary goods increase.

The optimal relocation strategy will prompt reshoring on one hand and nearshoring on the other. Optimization requires companies to manage their risks at adequate levels and utilize new opportunities that emerge. As a result, optimization will increase the brand value, and ultimately, expand investments and exports which in turn will create jobs. Of course how we relocate production will affect what types of jobs are created. For instance, reshoring is more likely to create jobs in the manufacturing sector, whereas nearshoring could create jobs in both the domestic intermediary goods industry and the related service industry (e.g. development, marketing, brand, etc.).

Large corporations will not find it difficult to optimize production relocation, as they already have started the process. The government’s role, in this case, is to respond to demands that may arise in the process. However, for some mid-sized firms, and the majority of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), optimization is a challenging task. For that reason, the government will have to concentrate its policies on supporting these businesses in line with the optimal relocation strategy.

This text was originally published on Yeosijae’s Korean homepage on May 19th, 2020.

< Copyright holder © TAEJAE FUTURE CONSENSUS INSTITUTE, Not available for redistribution >