Please join Yeosijae as we build a brighter future for Korea. Create your account to participate various events organized by Yeosijae.

- Insights

- |

- Next-Generation Values

“We must reserve a portion of the ‘200 million vaccines’ mentioned by Bill Gates for domestic use.”

“Korea’s success with the pandemic is a product of its ‘hurry, hurry’ culture – however, there are no guarantees for success in the next pandemic.”

Seminar by the Director of the Center for Vaccine Commercialization Technology Development, Baik-Lin Seong

Is South Korea’s model of pandemic responses successful? From how the world evaluates, the answer is yes—for now. Will we continue to be successful? It would be difficult not to have reservations about our future, considering many factors have contributed to our success with COVID-19. Where are we on vaccine development and vaccine sovereignty? Science is not political, but is it not also true that nationalism has considerable influence on the debate today?

The Future Consensus Institute (Yeosijae) invited the Director of the Center for Vaccine Commercialization Technology Development, Baik-Lin Seong, to hold a seminar on COVID-19 and South Korea. The center was established in April 2020 to respond to the COVID-19 crisis. Director Seong said, “Korea’s success with the pandemic is a product of its ‘hurry, hurry’ culture.” He warned, “We may be placed in a completely different position in the next pandemic.” He also advised against focusing solely on vaccine sovereignty and highlighted the need for a dual approach that involves international cooperation. He added that continued contributions to the world, comparable to South Korea’s global stature, are a prerequisite for the country to receive assistance from others.

[Summary of the Seminar]

The seminar and the debate that followed have been summarized below in a Q&A format. Ten participants from Yeosijae took part in the debate, including the Chair of Yeosijae’s International Advisory Board, Won-Soo Kim.

“Even in the event that a vaccine is developed,

safety and effectiveness remain an issue.”

Q. The COVID-19 vaccine race has begun in regions like the U.S., Europe, and China. How are these efforts panning out?

A. Currently, 118 vaccine development projects are underway, with 13 in clinical trials (WHO, as of May 15th, 2020). Fundamentally, vaccines are required two things – effectiveness and safety. In the case of vaccine for COVID-19, a third factor has been added to the equation: the speed of development. Though safety concerns have been overlooked due to the exigent circumstances of the crisis, the rapid development of vaccines is bound to raise safety concerns in the days to come. When vaccinations started for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), infection rate spiked as a result of antibody-dependent enhancement or ADE. The novel coronavirus shares many characteristics with the SARS virus (90%), rendering it impossible to rule out the possibility that ADE may occur again. Though concerns have been raised, solutions are yet to be presented. We still lack knowledge on many aspects of the issue.

had entered the third phase of clinical trials as of July 28th. (Source: Yonhap News Agency)

Q. Recent news has relayed the information that the COVID-19 vaccine developed by Oxford University and AstraZeneca has generated an immune response in all participants during the first clinical trials. What should we make of this news?

A. It is something to keep an eye on. The specific relationship between the antibodies of the potential vaccine and clinical efficacy is yet to be established. We should continue to monitor how this unfolds through the in- and post-trial phases.

Q. Dr. Anthony Fauci (Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases), who is leading American efforts to fight the coronavirus, said that he hopes for a vaccine by the end of 2020 or early 2021. Microsoft founder Bill Gates seems to share that optimistic view. What are your thoughts on this prediction?

A. Many scenarios are possible, depending on how we evaluate efficacy. For example, it is difficult to say that we will have a vaccine next year that can produce antibodies in seventy people out of a hundred vaccinated individuals. But if we are looking to develop immunity in twenty to thirty people, there are possibilities that a vaccine may be approved for its public benefits, despite its comparably lower efficacy—but that is still up in the air. Vaccine development is moving fast because there is a pressing need for the time being. However, problems will occur next year. Many discussion topics will emerge during the clinical phases. And for informational purposes, I would like to point out that there have been many cases where pathogens have gone unchallenged without any vaccines available for over a century.

“We are working to shorten the vaccine development process

from 10-15 years to 1-2 years.”

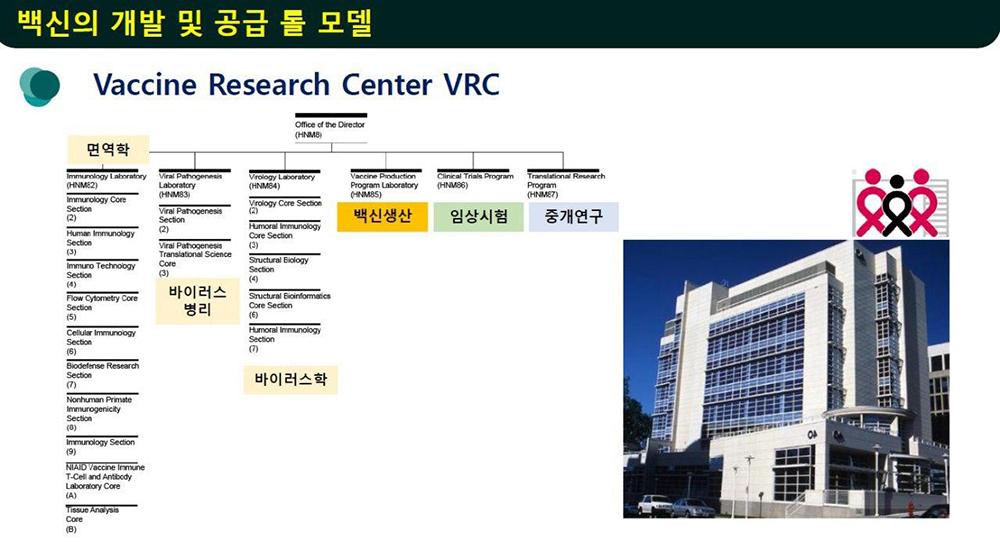

Q. Where is South Korea on COVID-19 vaccine development?

A. The news report from April that South Korea will invest 215.1 billion won over ten years in vaccine development is, in fact, unrelated to the COVID-19 vaccine. The government will be investing a separate sum of 48 billion won in supplementary budgets for the coronavirus vaccine. Vaccine development is currently underway in 10 institutions and companies in Korea, including SK Bioscience and Genexine. The urgent matter now is we shorten the development process from 10-15 years to 1-2 years. We are currently streamlining various processes and procedures to do this and are going beyond by building a basic technology support system. There are bottlenecks in vaccine development, and research studies are subject to a thorough review by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). Against this backdrop, the government is amending its legislation to enable rapid assessment of studies. It has already streamlined clinical trial review procedures and reduced the time required to commercialize the vaccine.

In June, two potential vaccines were approved for clinical trials in Korea. However, both of the candidates were nucleic acid (DNA) vaccines— a type of vaccine that is undermined by low efficiency and is yet to be commercialized for human use. Questions are certain to arise on DNA vaccines when it is potentially developed next year. More effective forms of vaccines are synthetic antigen vaccines. Developments for those vaccines are in progress at SK Bioscience, and clinical trials are projected to begin around September.

“Increased investment in the joint fund on Bill Gates’ part

requires additional investment from the Korean government.”

Q. In a letter to President Moon Jae-In, Gates wrote, “South Korea leads the vaccine development” and “if SK Bioscience succeeds in vaccine development, it would be capable of producing 200 million vaccines by next June.” He also expressed his intentions to increase investment in the Research Investment for Global Health Technology (RIGHT) Fund, which was established in partnership between the Korean government and the foundation. What is the significance of these messages?

A. SK Bioscience’s vaccine production capacity is on the level of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s standards on Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP). It will be manufacturing the vaccines developed by AstraZeneca. However, while the delivery of manufactured products may help the company produce a short-term profit, it will have a limited impact on South Korea’s fight against the COVID-19 crisis. We must avoid the situation where we are unable to have access to the 200 million vaccines produced annually. Consequently, the South Korean government should acquire the right to reserve a portion of the vaccines for domestic use. This is the basic idea behind advanced purchasing agreements or APA. With a government participating in a business deal, APAs have both public and private aspects. For that reason, vaccine developers are apt to act as deal mediators to facilitate a deal that will satisfy the national demand. At this point in time, I believe that there is a good chance for success.

The RIGHT fund is a separate issue. The Korean government and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation worked together to establish South Korea’s first international fund, committing 50% and 25% of the 50 billion funds, respectively. The message in the letter indicated Bill Gates’ desire to increase funding, and this would require additional investments from the Korean government and businesses. Many companies in Korea have already expressed their interest in joining the fund. It is now up to the South Korean government to decide the amount of increased funding. One proposal I would like to put forward is to tap into the vaccine and treatment funds from the supplementary budget to increase investments in the RIGHT fund. Doing so will add 180 billion won to the pool, creating a 230 billion won fund. The revamped fund would outstrip the size of the Global Health Innovative Technology Fund (GHIT), established by Japan a few years earlier. It has a total funding of 100 billion won with plans for additional investment in the future.

“Covid-19 vaccine may require two doses.”

Q. We hear a lot about universal vaccines.

A. The concept of universal vaccines originally emerged with the influenza virus. It has been discussed amongst vaccine developers for over a decade—in hopes to discover a “pivot” or an unchanging aspect of different versions of a virus that appears with the turn of a season. There are studies underway in Israel. However, the vaccine itself does not provide absolute protection against the flu virus. It is meant to provide supplementary immunization against viruses, to add to the other vaccines.

Q. Could that be applied to COVID-19?

A. I believe that we will eventually need more than one vaccine for COVID-19. Consequently, there is a potential for universal vaccines against the coronavirus.

“There is no chance of vaccine sovereignty without making contributions to the world.”

Q. Two global trends are emerging right now—vaccine nationalism and international cooperation. Is there an opportunity to achieve a balance between confrontation and cooperation?

A. That dilemma is what launched the Center for Vaccine Commercialization Technology Development. The government decided to respond to the calls for action, which have been made over the past decade. The vaccine market is small, accounting for only two percent of the total pharmaceutical market. In addition, clinical trials require a great sum of investment. Entry barriers to the market are very high, and vaccines—even when developed—are unprofitable as they eliminate the pathogen altogether. In our case, the market size becomes even more limited. Korean pharmaceutical companies lack the motivation to build a vaccine production capacity. This is why South Korea relies much on imports. In normal times, this would not cause any issues. However, once an outbreak of a virus occurs, demand skyrockets, and acquiring supplies becomes a challenge. In this context, Koreans have begun calling for efforts to secure vaccine sovereignty to protect itself. The nation’s vaccine self-sufficiency rate is at 40% at the moment, and the movement seeks to raise the levels to reach 80%. However, an international coalition on vaccines is imperative for South Korea to achieve vaccine sovereignty.

Q. Could you make further elaborations on that matter?

A. Korea’s response to COVID-19 was successful. We are not blowing our own horns when we say this, because other countries share this view. We have emerged as an advanced country. But that position entails corresponding responsibilities, and we must rise to meet those expectations. However, our mindset has not changed. Securing vaccine supplies would have been more convenient had South Korea made significant commitments to vaccine coalitions and supported the least developed countries. However, this is easier said than done. There is no return before an investment. As I have mentioned earlier, the vaccine market has a limited size and a low return-on-investment ratio, and this makes it impractical to work for complete vaccine sovereignty. Moreover, we will need cooperation and partnerships to achieve vaccine sovereignty. One might assume that government support and private-led development efforts would be sufficient to achieve our goals, but that is an overestimation of Korea’s abilities. What we need is a dual approach. I would like to emphasize once again that South Korea needs to consider making greater contributions to the world.

“Vaccine development is a game of patience for the public.”

Q. South Korea’s test kits have been instrumental in this crisis. Are there any possibilities of a trade between the test kits and the vaccine?

A. I do not think that would be possible as test kits are unsophisticated in comparison. I would argue that it could have been developed by a graduate-level researcher in an average lab. We simply emerged as the standard because we streamlined the early stages of development to promptly produce a COVID-19 test kit. Vaccines and test kits are two very different things.

Q. Then does that imply that South Korea could be in a completely different position when the next pandemic arrives?

A. There is a chance that we may not be in the lead. Accuracy and sensitivity are the two most important factors of test kits. However, we launched our kits immediately without taking the time to test the product. This was a case where Korea’s “hurry, hurry” culture led to success, though the rushed nature of the diagnostic tests initially delayed reviews from the U.S. FDA. The urgency of the situation placed constraints on the time for thorough assessments and permitted the use of the product. What I always argue for in government meetings is that, while speed mattered in the race for test kits, duration of immunity and effectiveness are the two essential factors of vaccines. We must not be disappointed by failures, and the government and the people should be patient as we wait for results. We should also take into account the distinctive features of the vaccine market and prepare for future outbreaks. The vaccine market is an area where the government must provide a market.

“The influenza virus has the potential to drive out the COVID-19 virus.”

Q. Some people predict that the COVID-19 virus will merge with the influenza virus in the winter.

A. Their basic structures are different, so I do not think that would be possible. However, I personally believe that the influenza virus will return to reclaim its throne as the most common virus and that there is a possibility that it could potentially drive away the novel coronavirus. Our immune system for the flu virus is able to cope with the coronavirus to an extent. In general, the public may think COVID-19 chased out the flu virus this spring. However, it is better to say that social distancing measures have slowed the spread of the influenza virus. We must not let our guards down on the threat of the flu virus.

“Tuberculosis kills over

2,000 people every year.”

I would like to add to the discussion the importance of tuberculosis. Every year over 2,000 Koreans—mostly young adults—die from tuberculosis. We have the highest TB death rate amongst the OECD countries, and this figure outstrips the number of COVID deaths by many multiples.

“We are in dire need of efficient governance.”

Q. What are your thoughts on your experience in working in a government agency?

A. We have streamlined the vaccine development process and are making full use of our financial and administrative resources. South Korea currently supports three vaccine candidates and has plans to expand this program. However, structural constraints of our government undermine efficiency, especially in cross-agency projects where much of our resources are used to facilitate cooperation. We are in dire need of efficient governance.

Q. Is there any progress on the government’s plans to establish a national virus research institute?

A. Kong-Joo Lee from Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST), who served as the President’s Science and Technology Advisor, took the lead in that issue. I believe that after several discussions, it was decided that the Ministry of Health and Welfare will be responsible for infectious diseases while the Ministry of Science and ICT will handle basic research of viruses. These departments will need to work together in the future. I believe that we should take this opportunity to define the roles of each agency before the institute is established.

|

About Baik-Lin Seong |

This text was originally published on Yeosijae’s Korean homepage on July 28th, 2020.

< Copyright holder © TAEJAE FUTURE CONSENSUS INSTITUTE, Not available for redistribution >