Please join Yeosijae as we build a brighter future for Korea. Create your account to participate various events organized by Yeosijae.

- Insights

- |

- Future Industries

- Sustainability

Ranked 20th on the Global Startup Ecosystem Rankings - Why Seoul is trailing behind Shanghai, Tokyo, and Singapore

Corporate giants need to collaborate with startups to create jobs

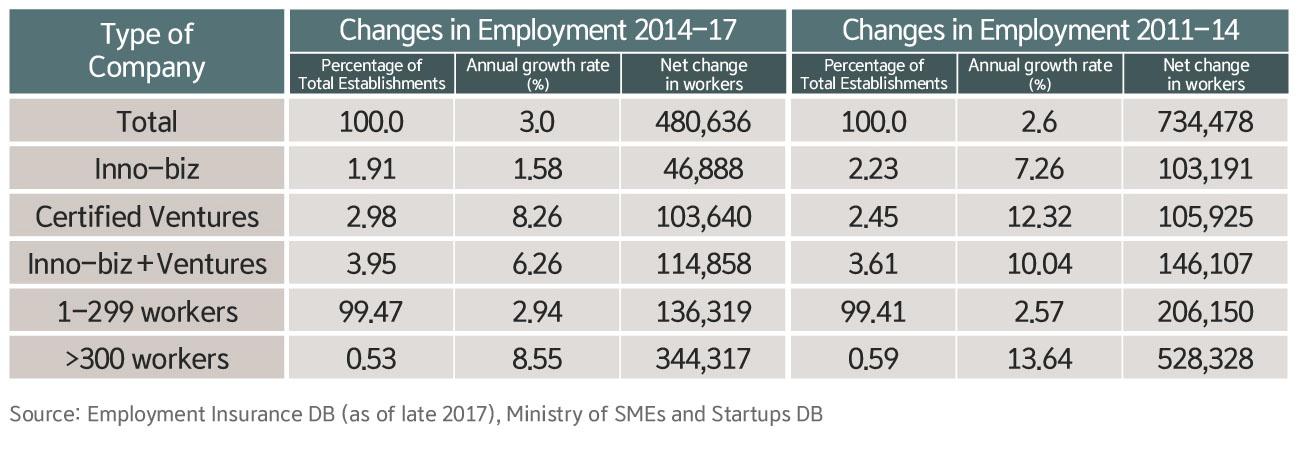

Large-scale economic crises always threaten the neediest people. As expected, the global pandemic and subsequent economic downturn have taken a toll on the number of jobs [Table 1], especially for the neediest population [Table 2]. Over the second quarter of this year, the number of employed persons declined, year-over-year, in the range of 350,000 to 470,000. It is expected that emergency relief packages announced in the second quarter would turn around the job market conditions in the coming months.

More unpleasant news is looming ahead. The pandemic seems unlikely to fade away in the near future, and we are approaching a time where an “economy with a pandemic” is our reality. We need to go beyond stopgap measures, such as the emergency relief package, to make mid-to-long term efforts to protect and create jobs. The Digital and Green New Deals, ‘K-New Deals’, announced on July 14th, aim to create jobs and bolster economic growth in the long-term perspective. They seek to create 890,000 jobs through the investment of 160 trillion won over the next three years.

The ‘K-New Deals’ are not a ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution to the current job crisis that cast a shadow over all sectors of the economy. They cannot fill all the gaps in employment. Not everyone will fully benefit from these programs, for some lack the capacity to leverage the opportunities provided by the initiatives. What breathes life and soul into public programs are companies that create jobs on the field—particularly startups in new industries. For new initiatives to promptly take effect on job creation, we must also devise policies to vitalize the employers, especially the startups.

The Digital New Deal is a type of initiative

that has been used in the past

In this context, it is worth exploring the implications of policies used in previous economic crises to create jobs. While the current situation is an entirely different matter compared to the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis and the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, similar trends are emerging in employment today— massive unemployment and reduced wages, particularly for the vulnerable population.

At least two common strategies can be drawn from our experiences of handling employment crises in the past: (1) large-scaled investment/job creation packages (a New Deal strategy) and (2) the vitalization of startups. Generally, in times of a crisis, governments endeavor to develop policies that will build and strengthen the social safety nets. However, these measures focus on protecting workers from job losses, and it would be difficult to consider them as policies to stimulate job growth. Against this background, South Korea took a different approach by building on the lessons from the past and applying the two aforementioned strategies in the Digital·Green New Deals.

History has a number of examples where countries focused on startups to deliver more jobs. This was the case for South Korea during the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis and the US and EU in the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. In 1998, the Korean government rolled out venture invigoration initiatives and policy funds to support the programs. Assigned with the mission to lead South Korea out of the financial crisis, the Kim Dae-Jung administration actively implemented the ‘Act on Special Measures for the Promotion of Venture Businesses’, passed in October 1997 during the Kim Yong-San administration, to vitalize the economy and create jobs.

After the 2008 crisis, the US and EU sough to catch two birds with one stone by focusing on startup vitalization to generate employment opportunities and stimulate economic recovery. The announcements of comprehensive strategies to promote startups began with the US in 2011, followed by the United Kingdom and EU. In January 2011, President Obama revealed the ‘Startup America Initiative’. The UK was next with the ‘Startup Britain Initiative’ in March, and in April, the EU Commission announced the ‘Startup EU’ to elevate the strategy to a continental level.

For traditional industries,

there is no going back to the pre-pandemic era

Economic trends since the 2008 crisis are expected to be more pronounced in the post-COVID-19 economy. Digital transformation and non-contact businesses will be the key drivers shaping the new economic landscape in the Post-COVID economy. The growing influence of artificial intelligence (AI)-based digital industries will make less room for brick-and-mortar traditional industries, reducing their employment.

Many, if not all, traditional industries may not return to business as usual even after the pandemic. This implies that it would be difficult to expect positive results from employment policies centered on these sectors.

Moreover, the digital economy raises a new set of concerns about employment. The rise of the platform economy and its monopolistic nature threatens to undermine job quality. In other words, the emergence of the ‘gig economy’ presents the risk of creating a surge of ‘gig workers’. While it is a fact that the digital economy generates new employment opportunities, we must take into account its potential to create unstable, temporary jobs as we develop our policies on employment.

The changing paradigm of the post-coronavirus economy appears to limit the effectiveness of macroeconomic policies, such as quantitative easing, in creating sustainable jobs. Quantitative easing policies can mitigate a shock in the labor market. What it cannot achieve, however, is the creation of sustainable jobs in an environment where labor is shifting toward the digital economy.

What is needed to develop

a Labor-friendly platform industry?

To offset the negative impact of the platform economy, we must promote the development of the platform industry on top of the efforts to nurture different digital industries that create sustainable jobs. Alternatives are emerging to reduce the degree of monopoly in platform industries while directing progress toward labor-friendly platforms. Platform firms established on socio-economic models are a case in point. 1) Such platforms will demand socioeconomic initiatives instead of macroeconomic policies to take root and grow. Certainly, platform industries are not the only component of the digital economy. Various methods can be developed and used in the digital sector to promote this industry that creates quality jobs. We are only constrained by the boundaries of our imaginations, rather than the innate limitation of the sector.

Promoting startups with an entrepreneurial spirit is

the key to surmounting the challenges of the employment crisis

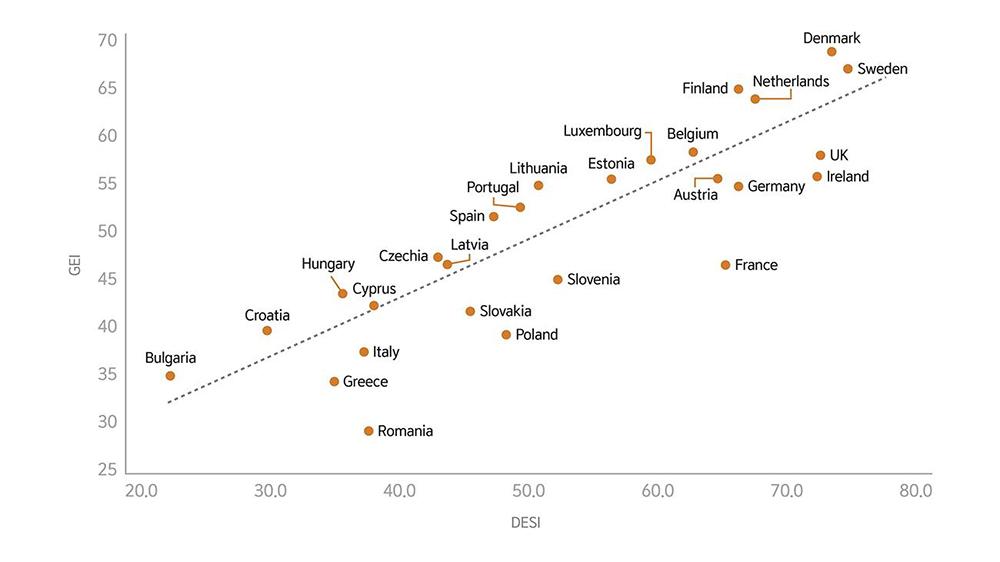

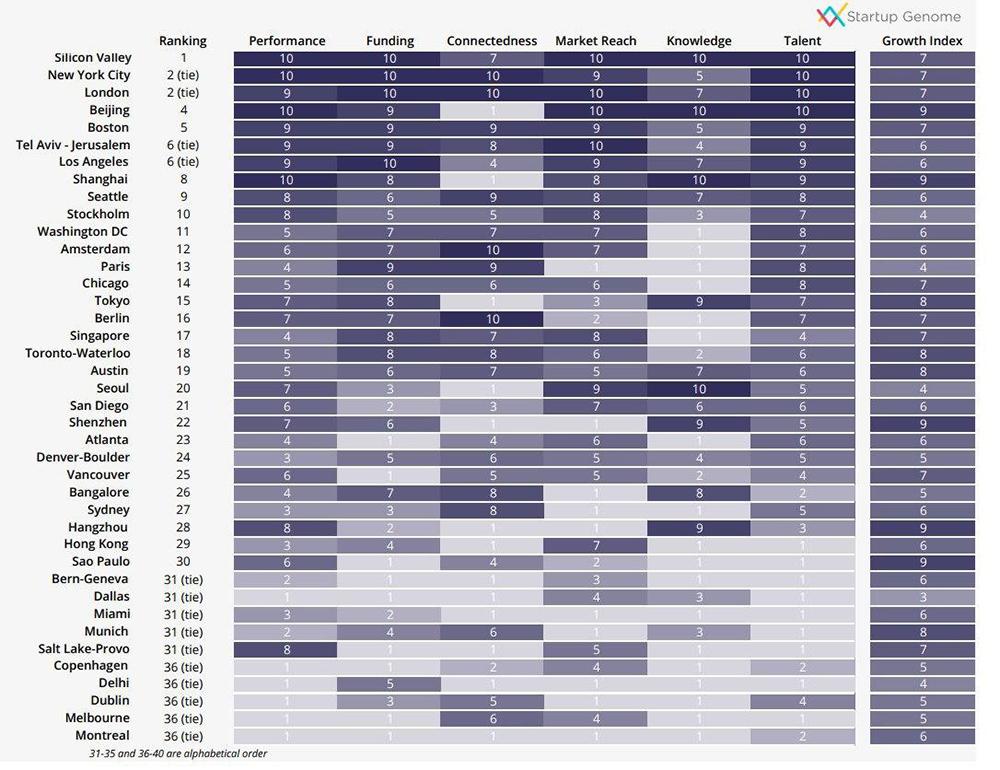

How do we fill the gaps in employment created by the declining role of the traditional sector, while mitigating the potential adverse effects of platform industries? Many answers could be presented, but I believe the fundamental solution is to promote the startups of the digital economy. The digital economy provides an enabling environment, where the importance of technologies and ideas outweigh capital. These characteristics provide an ideal environment to foster an entrepreneurial spirit. Vigorous entrepreneurial movement accelerates innovation [Figure 1], generates a new growth momentum, and provides the foundation for job creation [Figure 2]. Those with higher positions on the entrepreneurship index tend to have higher positions on the innovation index. This is why I believe that a new growth engine and a solution to the employment crisis can be found amongst startups armed with entrepreneurial spirits.

Then one could ask now if efforts to promote startups have a significant effect on job creation and if they could fulfill the traditional economy’s role in employment. The examples of South Korea and other advanced nations that are benefitting from startup-targeted strategies indicate positive responses to these questions.

For example, in South Korea, innovative businesses far exceeded the small and medium-sized companies (SMEs) and large corporations in job gains and youth employment. They have been the driving force of job growth for the overall SME employment, accounting for 70-80% of total job gains in SMEs between 2011 and 2017. Venture businesses, in particular, recorded gains that are on the same level as large corporations, unlike inno-biz (innovation+business) firms, and had a significant impact on the overall numbers.

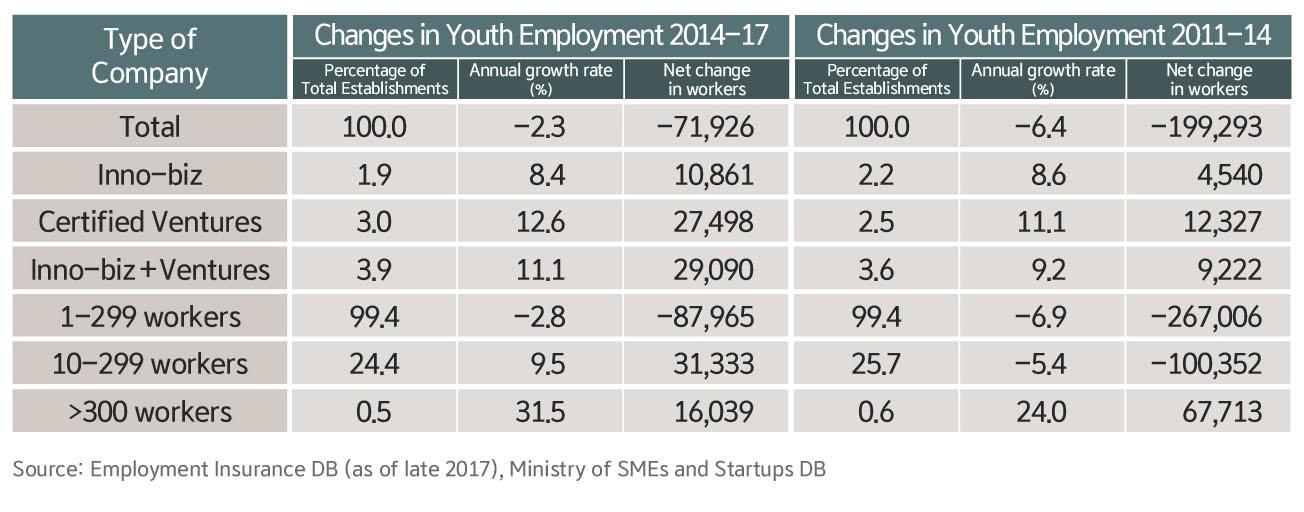

Innovative companies, together with large corporations, protect youth employment. Between 2011 and 2017, the total number of youth employed by SMEs decreased by 350,000. Contrastingly, innovative businesses hired additional 38,312 employees [Table 4], reaching almost half (or 45%) of employment gains by large corporations (added 83,752 jobs for the youth during the same period).

South Korean ventures employ more workers

than the four corporate giants

According to the 2019 Survey of Korea Venture Firms 4), South Korea had 36,065 venture businesses as of late 2018, recording a growth of 878 firms compared to the previous year. New venture investments are projected to exceed 4 trillion won this year. The combined sales of venture firms are 192 trillion won, second to only Samsung (267 trillion won) in the domestic economy. Considering the SK Group’s sales (roughly 183 trillion won), it could be said that venture businesses together form a company that is the size of the SK Group. 5)

Venture firms, with 715,000 workers, employ more people than the combined workforce of the four financial giants in Korea (668,000 workers). The average number of workers in venture businesses also increased to reach a level of 19.8 employees per company and recorded a growth of 5.3% compared to 2017. This shows that, as demonstrated before, the employment capacity of innovative companies is at the level of large corporations. Thus, doubling the number of such firms could increase the number of jobs by two-folds, generating an employment effect comparable to the establishment of four new giant companies.

Similar circumstances can be found in other advanced nations. High ranking countries in the ‘Global Startup Ecosystem Report’, including the U.S., the UK, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Finland, are finding results that testify to not only the employment effects of startups but also their significant contributions to economic growth.

(Source: Startup Genome. June 2020. ‘The Global Startup Ecosystem Report 2020’ (GSER 2020))

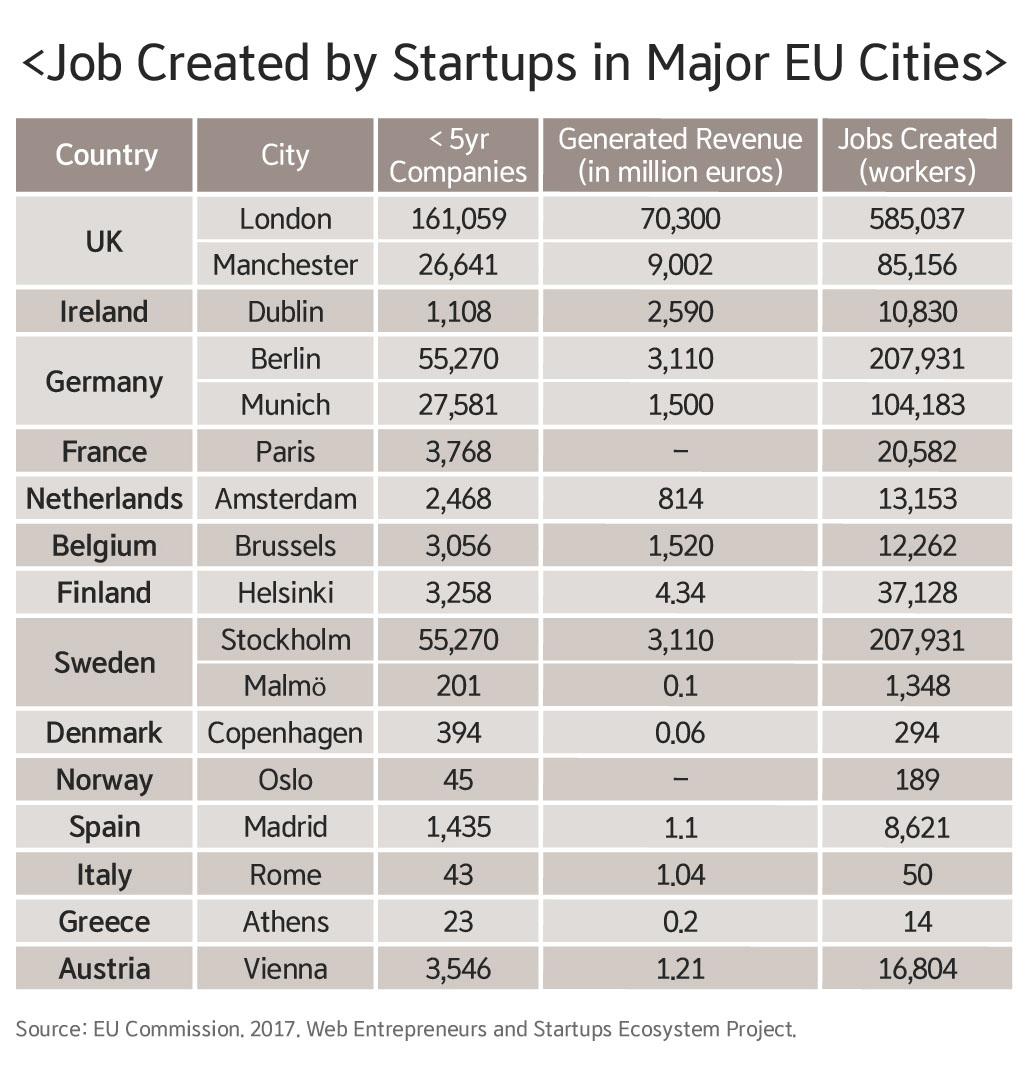

According to the data from the EU Commission, an estimated 290,000 EU startups (with less than five years of business activity) generated an employment effect worth 87 billion euros by employing roughly 1.1 million workers. European countries with the highest gains in jobs between 2006 and 2015 were Finland, Sweden, UK, and the Netherlands, and increases amongst these countries outstripped the EU average by over eight-fold [Table 6] 6). Robust efforts from the Commission to promote startups have created 250,000 new startup jobs annually, and Europe now seeks to generate 9.5% of its GDP from startup activities. (EYIF. European Startup Act, Vision 2020)

The employment generation effect of startups is closely related to the activity levels of each startup ecosystem. Countries with a high level of activities produce a larger number of jobs than others. The United Kingdom, for example, stands out above the rest in the absolute numbers of employment growth, and it is worth highlighting that the UK was able to create 700,000 new jobs in just three cities [Table 6].

Extraordinary times call for extraordinary measures

Missed opportunities are equivalent to failures

Through our experiences in South Korea and by examining the advanced nations of the EU, it is evident that nurturing startups is the most effective method to overcome the employment crisis of the digital economy in the post-coronavirus era.

Europe’s experience demonstrates the importance of efforts to promote the startup ecosystem. In contrast, despite our history of successful venture policies, South Korea’s venture ecosystem still has shortcomings that hamper the development of a virtuous cycle in the startup economy. Seoul ranks only 20th in the Global Startup Ecosystem Rankings [Table 5] and trail behind other Asian cities, including Shanghai, Tokyo, and Singapore. These assessments are quite disappointing, considering our potential in the digital economy, and the primary causes that contributed to this underwhelming performance have been found in the lack of robust early-stage venture investments and an active investment recovery market in South Korea.

With the announcement of the Korean New Deal, the government has begun efforts for policy improvements to promote the venture ecosystem. Various policy solutions will be explored in this process; however, I believe that the most effective solutions to the two shortcomings (the lack of early-stage investments and an active investment recovery market) are actions to promote corporate venture capital (CVC) from the early stages and the establishment of venture capital investment banks. Large firms with more assets and management resources should be able to fund venture companies and provide management and marketing expertise. These two issues have been long-standing challenges of our venture sector, and they must be resolved. 8)

Certainly, there is a chance that the perennial controversies over the separation of industrial and financial capital could arise. However, new policies always spark debates, incurring resistance from vested interests, which would only drag out the matter. Extraordinary times call for extraordinary measures. Time is of the essence, and we have to bear in mind that missed opportunities are failures in a different form.

1) A Platform Cooperative, or a Platform Coop, is a digital platform established based on the principle of ‘cooperativism’, and represents a new model of collaboration for the digital age. The sharing economy, a prime example of the platform economy, provided a capitalist business model that utilized digital platforms to ensure profit for the few. It generated platform workers in a labor market that does not recognize workers’ basic rights. Platform Coop emerged as an alternative business model to address the downsides of the corporate model of the sharing economy while retaining access to the technologies of the platform economy. Kim Eun-Gyeong. Jan. 2020. ‘Platform Coop, the Starting Line of the Fair Economy’. Gyeonggi Research Institute.

2, 3) Yoon Yoon-Gyu, Bang Hyeong-Jun, Nho Yong-Jin. ‘Innovative SMEs and Job Creation for Youth’ KLI Employment & Labor Brief No. 87 (2019-02)

4) Ministry of SMEs and Startups and Korea Venture Business Association. Dec. 2019. ‘2019 Survey of Korea Venture Firms’.

5) Largest companies in Korea by sales (as of May 2019, in wons): Samsung (267 trillion), SK Group (183 trillion), LG Group (126 trillion), and Posco (68 trillion).

6, 7) Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency. 2018. ‘European startup ecosystem and cooperation’. Global Market Report 18-029.

8) Chun Byoung-Jo. 6 Jan. 2020. ‘We must establish venture-specialized investment banks’. Yeosijae weekly insights.

This text was originally published on Yeosijae’s Korean homepage on July 24th, 2020.

< Copyright holder © TAEJAE FUTURE CONSENSUS INSTITUTE, Not available for redistribution >