Please join Yeosijae as we build a brighter future for Korea. Create your account to participate various events organized by Yeosijae.

- Insights

- |

- Future Industries

[Discussion / North Korean Economy] What is the current state of the North Korean economy amid sanctions, COVID-19, and flooding?

- Facing the worst economic outlook amid the triple whammy of crises (sanctions, COVID-19, floods)

- North Korea admits its economic plans have failed; still, its economy is more self-sufficient than that of the “Arduous March” period

- Its success in localizing metals and chemical industries will decide whether the country can withstand the economic shocks

Workers’ Party, Chairman Kim Jong-Un acknowledged that his economic plans have

failed and pledged to unveil a new five-year economic blueprint. (Source: Yonhap News)

Through official announcements, the North Korean government acknowledged the policy shortcomings of the regime’s five-year plan to boost the economy through Juche (or self-reliance). This rare admission of failure to meet the economic vision laid out in 2016 by the supreme leader himself has raised eyebrows in the community, sparking debates on its interpretation.

One thing is certain about this unprecedented move. It indicates that the North Korean economy is in a dismal state. The triple whammy of crises—sustained sanctions, COVID-19, and flooding—and their fallouts have pushed the country into a tight corner. The international credit rating agency Fitch estimates an 8.5 percent contraction of annual GDP growth rate for the North this year. This would mark the country’s worst economic downturn since the 6 percent contraction in 1997, which occurred during the North Korean famine (otherwise known as “the Arduous March”).

On the other hand, some consider the frank admission of difficulties as a sign of confidence, to generate national solidarity and propel the country out of the crisis with a new vision. Chairman Kim plans to hold a Workers’ Party congress in January to unveil a new five-year economic development plan. In this context, what is the current state of the North Korea’s economy, and is it comparable to its conditions in the 1990s famine?

The Future Consensus Institute (Yeosijae) set out to assess the state of the North Korean economy by hosting a discussion forum joined by three experts on the North — Young-Hoon Lee (Senior Economist, SK Research Institute of SUPEX Management), Hae-Won Jang (Researcher, Hana Institute of Finance), and Ji-Young Choi (Research Fellow, North Korea Research Division, Korea Institute of National Unification (KINU)). Senior Economist Lee worked at the Bank of Korea (BOK) before becoming a Senior Researcher at KINU. Research Fellow Choi was also an Associate Research Fellow at the BOK. Researcher Jang studied finance and accounting in North Korea and worked as an accountant before studying the North Korean economy in South Korea. The discussion was chaired by Yeosijae Policy Fellow and former diplomatic correspondent for YTN Son-Taek Wang.

[Participants]

Young-Hoon Lee (Senior Economist, SK Research Institute of SUPEX Management)

Hae-Won Jang (Researcher, Hana Institute of Finance)

Ji-Young Choi (Research Fellow, North Korea Research Division, Korea Institute for National Unification)

Son-Taek Wang (Yeosijae Policy Fellow and former diplomatic correspondent for YTN) [Chair]

“North Korea was braced for the first shock of increased sanctions.”

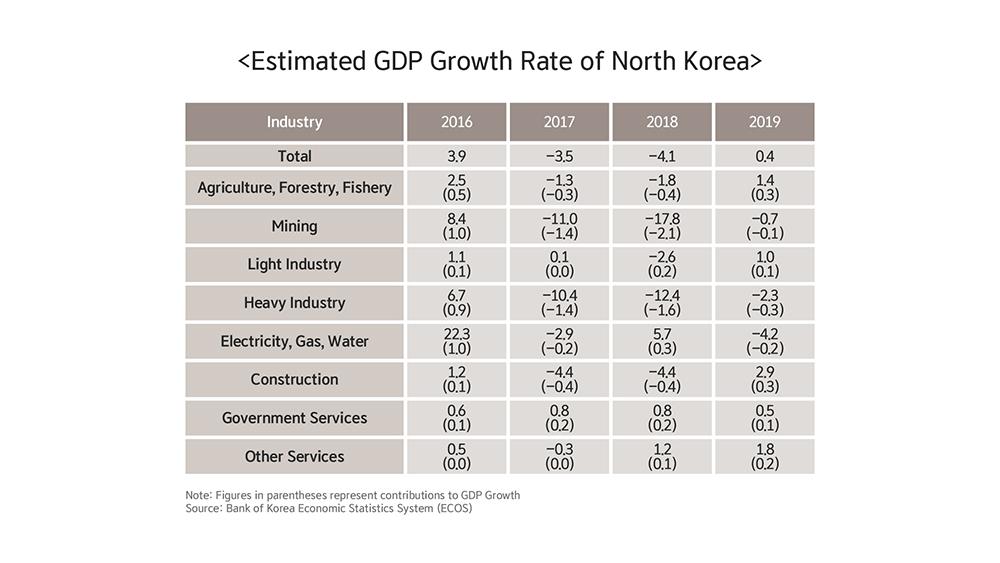

Analyzing the country’s economy using the China-North Korea trade volume and the Bank of Korea (BOK)’s estimates of North Korea’s gross domestic product (GDP), KINU Research Fellow Ji-Young Choi described the sanctions from 2016 as the “first economic shock wave”. China had accounted for over 90 percent of North Korea’s trade before the sanctions. However, bilateral trade volume plummeted after 2016, cutting North’s exports to China by almost 90 percent. The key export industries, the mining and heavy industry, were dealt with a heavy blow, and as a result, North Korea experienced negative growth in the consecutive years of 2017 and 2018. However, according to the BOK, the North was able to turn its economy around in 2019 by recording estimated GDP growth of 0.4 percent. Choi assessed that this was largely the result of growth in the agriculture and services industries, especially in the tourism sector. The regime made an all-out effort to boost agricultural production, so much that imports of fertilizers increased, not decreased, even after the sanctions were imposed. As a result, the country had what it claimed to be one of its “best harvests on record” in 2019. Even South Korea’s Rural Development Administration estimated slight increases in the North’s agricultural production, and it is considered that this helped drive growth in North Korea.

SK Research Institute Senior Economist Young-Hoon Lee stated that North Korea was able to expect the imposition of sanctions and make preparations against the first economic shock wave. The regime sought to mitigate the impacts of the shock by providing more autonomy on one side while increasing restrictions on the other, a style of economic policy that is often attributed to Kim Jong-Un. North Korea implemented the socialist system of responsible business management to provide autonomy for corporate management and added market dynamics to the economy by increasing competition between businesses and individuals through various consumer goods exhibitions. At the same time, the government clamped down on the flow of goods and capital to prevent disruptions in domestic capital flows in the event that the sanctions are kept in place for an extended period of time. Increased competition in the consumer goods market, in conjunction with active public investments in science and technology and talent development, shifted the regime’s policies toward localizing strategies that seek to improve the quality of outputs and increase productivity. Hana Institute of Finance Researcher Hae-Won Jang added that measures to expand financial functions, including the introduction of an independent accounting system for commercial banks and efforts to promote payment cards, have elevated the stature of banks in North Korea. North Koreans that were once unaware of locations of their near-by banks now stand in lines in banks.

Research Fellow Choi believed that the promotion of the tourism sector, one of the main driving forces of growth for North Korea in 2019, was another part of North Korea’s efforts to cope with the sanctions. The North began emphasizing cooperation with China in tourism after the sanctions were imposed. It is estimated that the country has raised over 100 million dollars of foreign currency annually by attracting 200,000 Chinese tourists in 2018 and 300,000 in 2019. Compared to the number of visitors from China before the sanctions, this is a four to six-fold increase in the number of Chinese guests. North Korea invested in tourism to offset the negative implications of sanctions on its trade deficit and to raise foreign currency. At one point, it was reported that North Korea plans to attract one million tourists, which would generate roughly 500 million dollars in foreign currency. The construction of the Wonsan-Kalma coastal tourist area, which was scheduled to be completed by April of this year, was also a part of the regime’s tourism investment initiative. However, the emergence of COVID-19 in January urged North Korea to close its borders. This derailed plans to expand the tourism sector. The completion of the Wonsan-Kalma coastal tourist area has been delayed, and a result, Chairman Kim attended the groundbreaking ceremony for Pyongyang General Hospital in March instead.

“COVID-19 was an unexpected shock that could not be prepared for in advance.”

Contrary to the sanctions, COVID-19 was an unexpected second economic blow for North Korea. Research Fellow Choi said while sanctions affected the country’s exports and public sector, COVID-19 has taken a toll on the imports of non-capital goods, which were originally unaffected by the sanctions, and consequently, the negative implications of the pandemic are spreading to the public sector. In other words, restrictions in exports may have dented the country’s foreign currency earnings, but reductions in imports have diminished the supply of goods, which in turn damaged the country’s finances.

Market prices and exchange rates, which had stabilized from the earlier shock of the sanctions, regained volatility in early 2020 when the country experienced extreme fluctuations in February and April. Research Fellow Choi said it is likely that the first swing in February was caused by market sentiment around border lockdowns rather than the actual decreases in supplies. This is based on the fact that the same trend occurred when sanctions were first imposed and that February is too early for the effects of border shutdowns in January to reduce the number of supplies. For the changes in April, she believed that policy changes were the main drivers of volatility. North Korea implemented various policies, including the issuance of public bonds, to collect foreign currency from the market, and has reportedly placed restrictions on imports of “unnecessary” or non-essential items in the spring of this year.

However, market prices and currency exchange rates began to stabilize in May, and they currently remained steady. Choi said she believes this is the result of food reserves and government controls. She said price volatility for a given year is determined primarily by the amount of harvest in the previous year. This is because the government reserves food from the harvest and regulate distribution in the following year to reduce price volatility and stabilize the market. She assessed that North Korea was able to stabilize the market prices in the first half of this year thanks to a bumper harvest from 2019 and tight controls on food distribution. This success also indicates that the North Korean economy remains in reasonable health, controllable by government measures. Senior Economist Lee also noted that COVID-19 had a limited impact on the country’s economy. He said while the pandemic has cut trade, signs of business closures and factory shutdowns are yet to be found in North Korea.

“Times are better now compared to the days of Arduous March.”

From sanctions to COVID-19 and flooding, a series of challenges have emerged for North Korea, and some have compared its current economic situation with the “Arduous March” period. The three participants agreed that the country is going through difficult times; however, they argued that its current form does not compare to the state of the country during the devastating famine. Research Fellow Choi explained that the grim conditions of the 1990s were due to a shortage of oil and a food crisis caused by a decreased supply of fertilizers. She pointed out that today, despite sanctions and reduced trade, supply chains for oil and fertilizer remain uninterrupted for North Korea. UN sanctions have not disrupted the supply of oil, since the cap was set at the pre-existing level of imports, and imports of fertilizers have increased instead. Consequently, she believed that a food crisis would not occur, contrary to the Famine in the 90s, as long as the supply chain for oil and fertilizer remain uninterrupted for North Korea.

Since the sanctions were imposed, North Korea has successfully localized the production of consumer goods, producing 80 percent of its total volume of grocery consumption domestically. Against this background, Choi believed that short-term disruptions to trade from border lockdowns would not have a significant impact on the North’s food supply chain.

Researcher Jang agreed that the current situation would not reach the levels of the Arduous March period considering the “marketization” efforts North Korea has made over 30 years to build self-sufficiency in the economy. Using the knowledge gained by both the government and the people over the years since the traumatic experience in the 90s, the North has maintained stable market prices amid the three crises. Jang explained that this is why North Koreans believe that the current situation is “better than the Arduous March” period, despite the ongoing economic crisis.

“The fate of North Korea’s economy will depend on

whether the country can localize the production of intermediate goods.”

However, problems will emerge if the current crisis is protracted. The three participants were skeptical about North Korea’s ability to withstand a long-term crisis with the two strategies that they used in the first half of this year. Lee said the North was able to implement wartime-level draconian controls because it faced a crisis that could not be prepared for in advance. However, he pointed out that if the bilateral trade with China does not resume for an extended period of time, it is highly likely that the country will suffer from increased economic uncertainty. North Korea has been strongly emphasizing intermediate goods after successful efforts to localize the production of consumer goods. In this context, Lee believed that the local production of these goods, especially metals and chemicals, will determine whether North Korea will be able to withstand economic sanctions for an extended period. Research Fellow Choi added that halted trade, reduced production activity, supply chain disruptions for fertilizers, and extensive damages from flooding would lead to a subsequent drop in production in 2020. Thus, she argued that there is a need for continued monitoring of the North Korean economy, as forecasts indicate increased economic uncertainty for the country in 2021.

Is there a way to facilitate cooperation between the two Koreas?

The participants also shared their thoughts about potential areas of cooperation between the two Koreas. Considering the most realistic options, Senior Economist Lee suggested bilateral cooperation in health and the environment. Research Fellow Choi said supposing that sanctions are lifted, agricultural modernization projects for cooperative farms would be the most pressing concern for North Korea. Her argument was that it would be difficult for North Korea to achieve economic growth without improvements in production levels since production output remains low despite producing 80 percent of the total volume of grocery consumption domestically. Lastly, Researcher Jang highlighted an initiative that was once pursued but dropped. She underscored people-to-people exchanges, especially for scholars and experts, noting that projects for this initiative can begin at any time if South Korea and North Korea are willing to do so, as this is an area that is not restricted by the sanctions.

This text was originally published on Yeosijae’s Korean homepage on August 27th, 2020.

< Copyright holder © TAEJAE FUTURE CONSENSUS INSTITUTE, Not available for redistribution >