Please join Yeosijae as we build a brighter future for Korea. Create your account to participate various events organized by Yeosijae.

- Insights

- |

- Future City/Future Housing

- Sustainability

Improving South Korea’s approach to Urban Regeneration - Facilitating “private sector participation” in urban regeneration projects

South Korea’s approach to Urban Regeneration and its weaknesses

Propelled by rapid industrialization, urban regions in South Korea grew by leaps and bounds over the last decades. Large cities, in particular, became central hubs for innovation. However, rising expectations of its residents grew at a much faster speed than the physical growth of urban areas.

When new town development projects and urban reconstruction/redevelopment initiatives from the 1980s and ’90s reached their limits, “Urban Regeneration” emerged as an alternative public policy for cities. The new government initiative began with Lee Myung-Bak administration’s “New Town Project”, followed by Park Geun-Hye administration’s “Urban Regeneration Project”, and was expanded even further under the leadership of President Moon Jae-In. Though they began with the ambitious goal of creating a better urban environment, current circumstances indicate that there are several limitations and contradictions in regeneration schemes. These concerns have been raised by many experts, and various discussions are underway regarding urban regeneration. With presidential elections coming up in 2022, Yeosijae assessed that this was an issue of importance and invited experts to discuss this matter. We would like to share the insights we have gained from our discussions in parts. In this first text, Construction and Economy Research Institute of Korea Associate Research Fellow Tae-Hee Lee discusses how the current model of urban regeneration undermines sustainable development.

from the Japanese colonial era (Source: Tae-Hee Lee)

Right- Street lined with murals as part of Garibong-dong Urban Regeneration Project

(Source: Seoul Urban Regeneration Center)

A large majority of ‘New Town Projects’ were called off

during the Global Financial Crisis

After the Korean war, South Korea experienced a period of great economic development, which prompted rapid urbanization of its towns. At the time, Seoul, Busan, and cities alike lacked the necessary infrastructure to accommodate the sudden influx of new residents and faced shortages in housings, roads, schools, and other underpinning structures. Moreover, the government lacked the financial capacity to launch development projects to solve the housing crisis. Roads and buildings were constructed without careful planning, and the urban poor flocked to the slopes of mountains to build illegal dwellings.

As the economy grew and housing issues were resolved to an extent, people began to put greater emphasis on the quality of urban environment and housing. Residential areas that lacked basic infrastructure and had poor living conditions became slums. Moreover, aging infrastructure emerged as a problem for the urban population as the years went on. Amongst these deteriorating areas, zones with commercial value were developed through reconstruction/redevelopment projects that were funded by private investments.

The drive for redevelopment/reconstruction projects started and peaked in the early and mid-2000s when the government launched a “regeneration promotion project”, or what is known as the “New Town Project.” However, a large majority of these programs were called off due to the shock of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. And when the profit-seeking nature of redevelopment projects caused issues to surface, such as the involuntary displacement of people, people began to look for alternative approaches to urban development.

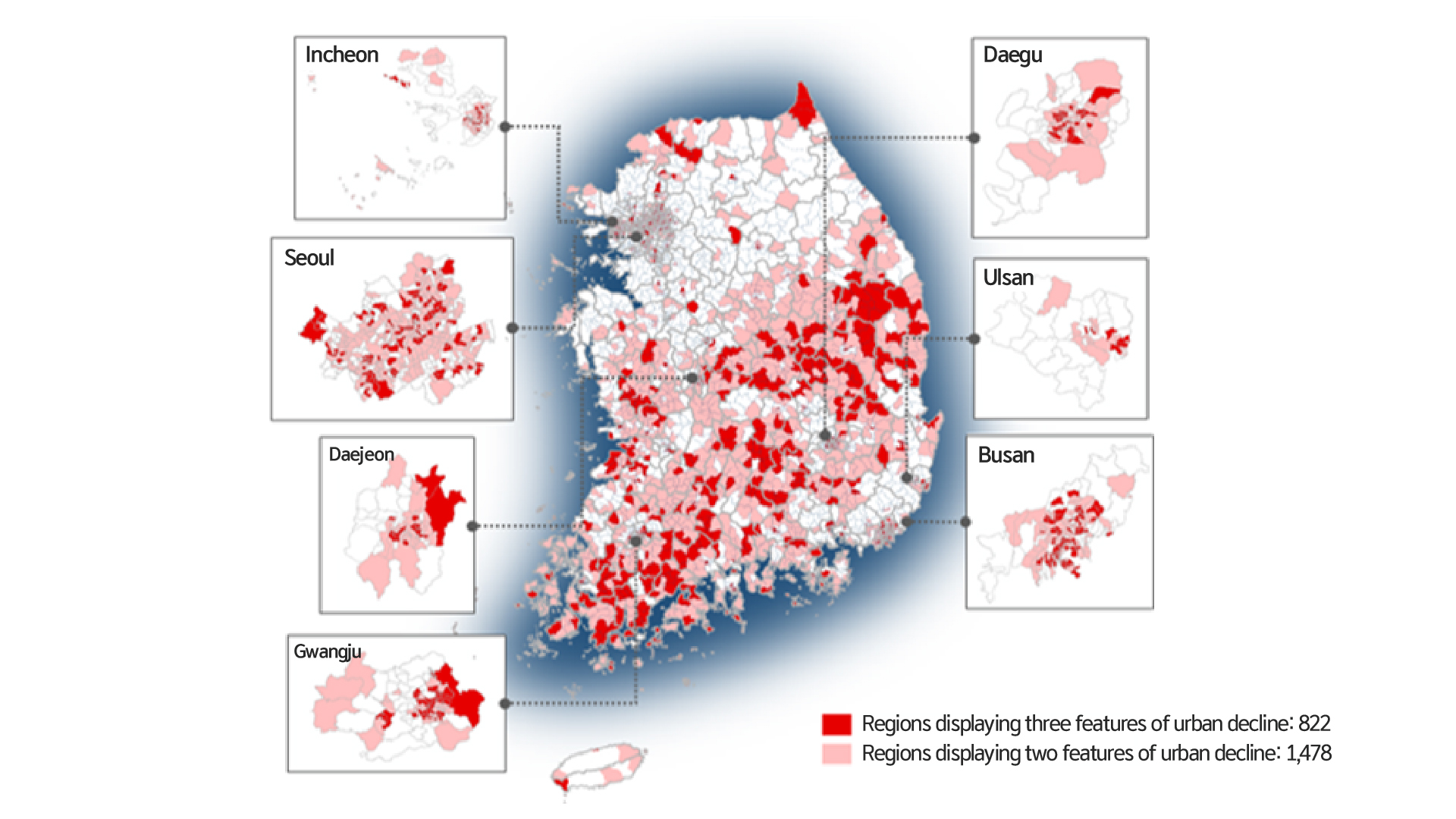

Over the years, many problems were exacerbated in urban areas, such as the rise of slum housing and aging infrastructure, as did national concerns of low fertility rates and the aging population. And despite continued policy efforts for balanced national development, population density around the capital city increased while the decline of local flagship industries began to pose a threat of “extinction” for other regions.

Launched by the Park administration,

Elevated to National Agenda by the Moon administration

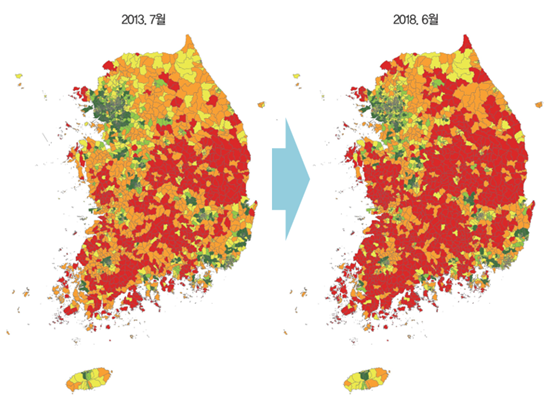

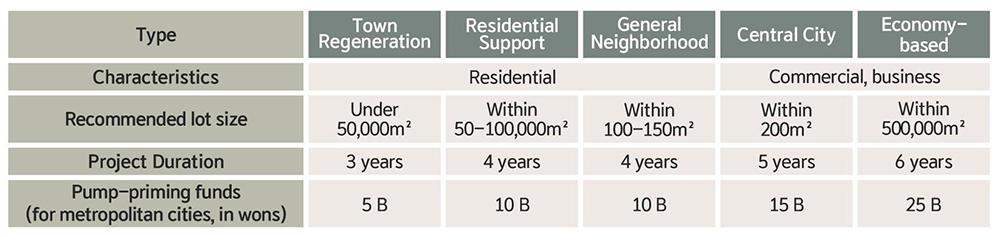

Against this backdrop, South Korea formally launched urban regeneration projects in 2013, after passing the 「Special Act on Promotion of and Support for Urban Regeneration」. These initiatives sought to revitalize cities that are experiencing depopulation, change of industrial structure, population aging, and other types of decline through selective administrative/financial support. The project size of urban regeneration programs varied from 50,000㎡ to 500,000㎡, and fundings ranged from 1 billion won to 50 billion won per each region.

While these numbers may seem significant, they are nowhere near the amount needed to change the fate of declining cities and to make drastic improvements to living conditions in under-developed regions. Road expansion, for example, could easily cost over 10 billion won in high priced areas due to costly land acquisition compensations. Consequently, policies have been developed not to vitalize cities solely through public funds, but for them to act as funds that “will prime the pump” for additional public and private investments.1) For this reason, public expenditure for urban regeneration projects are called “pump-priming funds.”

(Source: Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport)

Urban regeneration initiatives that began under the leadership of President Park was elevated to the national agenda by the Moon administration under the “Urban Regeneration New Deal.” The incumbent government and the ruling party defined this program as a “national urban innovation project” that seeks to improve “housing welfare, social cohesion, urban competitiveness, and job creation.” And in 2018, the government presented the “Urban Regeneration New Deal Roadmap” to outline its plans to select 100 regions every year to invest 10 trillion won worth of public funds annually. Starting with 68 development projects in 2017, the government invested in 99 regions in 2018 and 116 in 2019. Including 46 investments from the Park administration period, regeneration projects have been started or completed in a total of 329 areas since the program began. Moreover, 120 additional regions are set to receive investments in 2020.

Excessive government intervention in urban regeneration

However, several issues have been raised about urban regeneration projects, and they broadly fall into three categories: problems of process, contents, and outcome.

First, difficulties in the “process” stage stem from excessive government intervention in regeneration programs. The private sector (second sector) and the local community (third sector) has a limited role in renewal projects. Even regeneration activities for downtown areas, where the majority of commercial activities and administrative functions take place, have low private sector involvement, and the same circumstances can be observed in other metropolitan cities and large cities with a population of over 500,000.2) Projects for residential areas also receive similar criticisms for their disproportionate share of public entities and insufficient community engagement.3)

Another highly criticized aspect of urban regeneration is project content. Though regeneration policies aim to vitalize declining/under-developed regions and improve living conditions in residential areas, many development plans include irrelevant or inadequate programs. As a result, various facilities related to policy trends, such as “youth and startup”, are being built in regeneration sites throughout the country without careful examination of local needs, characteristics, and the ripple effect of projects. And despite increasing criticisms of youth malls, similar facilities are not only under construction throughout the country, but even in regions with a small share of youth in the total population. Consequently, many of these facilities are left almost abandoned by the time the projects reach their final stages.

There are many other examples of failed regeneration schemes throughout the country, including programs for murals, street renovations, socio-economic organizations, community-led projects, and shared community facilities, and this has fueled a growing skepticism on whether regeneration projects have made considerations for local characteristics, project effectiveness, and sustainability of development.

Not enough focus on key areas of urban regeneration:

Basic infrastructure, road environment, and industrial competitiveness

In addition, most projects focus on small-scale rehabilitation programs, while only a handful of projects prioritizes infrastructure development (e.g., roads, parks, public transport reforms, and renovation of old architecture) and spatial restructuring. Projects that address the root causes of urban decline—the decline in industry and the loss of jobs—are also scarce.

“Regeneration schemes only serve to paint walls.”

Reasons behind the criticisms

These issues in project implementation and content consequently gave rise to challenges in delivering results. Despite vast amounts of public funding (from 10 to 50 billion won), the effects of urban regeneration programs on industrial competitiveness, urban vitalization, and living conditions have been unconvincing. The narrow scope of the scheme limited the use of spatial restructuring, infrastructure development, and other projects that tackle the fundamental cause of the problem, and undermined the effects of regeneration programs on industrial competitiveness and job creation. It is for these reasons that the costly initiative is criticized as a “public project that only serves to paint walls” and is doubted for its capacity to “regenerate” cities. In fact, some of the regions that have just recently completed regeneration projects are starting movements to launch “public redevelopment” programs instead.4) I expect more cities will join this movement for redevelopment projects once they discover that the effects of regeneration schemes are disappointing.

Urban regeneration loses momentum

once public funds are exhausted

More importantly, trends across different regions indicate that state-led regeneration projects lose their traction once public funds are exhausted. In most cases, urban regeneration and communities around them run out of steam and disappear when government funds run out, as they were the only lifelines that supported them. Only a small number of projects are funded by private entities, and this has made it difficult for cities to maintain growth momentum and sustain employment after public projects are completed.

Addressing the issues of urban regeneration is a challenging task, as they stem from a myriad of factors. Multifaceted problems generally require multidimensional solutions. Nevertheless, there are rooms for improvement, and I would like to offer the following as critical areas of focus.

Returning to the basics of urban regeneration

through reforms and policy changes

The Urban Regeneration New Deal currently offers four incoherent goals of improving housing welfare, social cohesion, urban competitiveness, and job creation. On top of these fragmented goals, regeneration projects also contain initiatives to pursue green construction, innovation districts, smart cities, and other national agendas at the same time. This is because up until 2018, when the struggle to obtain government funding was at its height, project proposals received additional points in the selection process if they included programs for other national projects.5) Revision of proposed project activities becomes difficult once selected, and this constrained project execution to the boundaries of existing plans.

Of course, government agendas and the four goals of urban regeneration outlined above are important public policies. However, we must remember not to put the cart before the horse. There should be a different degree of importance between the goals of urban regeneration and other public agendas in our efforts against the shrinking urban economy, declining downtowns, and exasperating housing crisis. Investments for youth entrepreneurship zones, rental housings, and “eco-remodeling,” for instance, would hardly qualify as efficient use of budgets in cities with affordable rent for real estate space and an increasingly aging population.

Addressing the issue of urban decline is a challenging task that requires a tremendous amount of resources; however, the government’s budget for urban regeneration is very limited. Consequently, we must restructure our Urban Regeneration New Deal around urban competitiveness, downtown areas, living conditions, and other fundamental aspects of urban regeneration. Moreover, we need to make efficient use of available public resources to help solve problems in different regions.

Broadening the scope of Urban Regeneration

to consider growth for cities as a whole

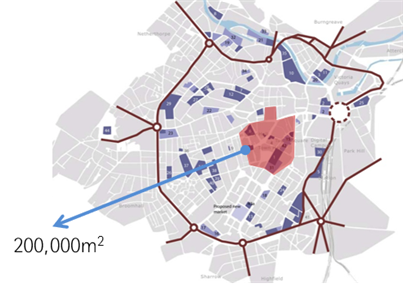

Two problems are evident in our current regeneration framework. First, the project implementation area (or the revitalization zone) is limited to just small sections of cities compared to their size and resident activity areas, while the government’s approach to budget spending and project participation is overly narrow. Even projects for downtown areas, which are relatively large in size, target a space that is only about a seventh of Nonhyeon 1-dong (a small district in Seoul). Programs that are critical to vitalize residential and commercial areas, such as accessibility and learning environment improvements, are inconceivable in such a confined space. Moreover, the narrow scope of the initiative raises questions on the integrity of the program, given that funds are provided only to arbitrarily selected areas of declining/under-developed cities. It should be noted, however, that regeneration zone designation is a temporary measure that loses its value once government programs are completed. Consequently, we must expand the spatial scope of urban regeneration projects to ensure that improvements are sustained and expanded beyond project completion over the medium and long term.

Second, our current approach to urban regeneration is very short-sighted, in that regeneration initiatives are detached from other urban policies. Many municipalities, even today, are promoting regeneration projects while maintaining their investment in programs that caused the decline of cities in the first place, including the development of new towns and mega shopping centers and the relocation of public offices and transportation facilities. Even cities experiencing a decline overall due to underperforming flagship industries show a lack of coordination between urban regeneration schemes and industrial/economic policies. This fragmented approach to urban regeneration stems from urban regeneration policies that often focus on specific regions of cities instead of capturing the city as a whole.

In other words, urban regeneration projects today are “missing the wood for the trees.” Consequently, we must expand the scope of regeneration programs and coordinate them with key urban policies (e.g., spatial, industrial, and transport) to enable consistent action in cities.

and South Korea’s Urban Regeneration New Deal project

(central city type, in red)

(Source: Sheffield City Centre Masterplan, modified by Tae-Hee Lee)

There is no sustainability

Without profitability

As illustrated above, the current urban regeneration policy incorporates plans for different national agendas (including programs for youth, entrepreneurship, rental housings, and the Green New Deal), and much of these goals have been carried over to project execution. Mutually beneficial agreements, special commercial districts, and other anti-gentrification policies have been highlighted to avoid adverse impacts on cities. Furthermore, the public value of projects has been given a priority in urban regeneration schemes, while profit-seeking activities have been discouraged by various stakeholders and even the media.6)

Empty shopping districts and deserted youth malls

As a result, private investment in urban regeneration has been limited, and most regions were left with only state projects to drive change in their region. Sustainable jobs were not created, and several public facilities (e.g., local museums and community facilities) had to close after government programs were completed due to a lack of funding. Special shopping districts and youth malls stand empty, and socio-economic organizations have ceased to operate. Consequently, their effect on creating economic value added has come into question.

Against this backdrop, I believe that we should stop giving priority to the public value of regeneration projects to pursue plans for improvements over the mid to long-term period. Moreover, we need to work to improve the perceptions of profit-driven projects and private investment in urban regeneration. Government-led regeneration programs are only temporary, and pump-priming funds are insufficient to solve various problems of each city. Private investment is necessary to expand the total funding pool and to create sustainable jobs that will last beyond project completion. Consequently, we must improve the perception of profitability in regeneration projects. Instead of sidelining private businesses in regeneration programs, we should consider them as our partners. Doing so will allow urban regeneration to break away from the current cycle of failure, where regeneration ends with the completion of state programs, and enable public funds to serve its role as “pump-priming funds” that can facilitate private participation and economic recovery.

“Rehabilitation” is not the only solution;

Adapting projects to meet local needs

Urban regeneration policies are currently implemented in two ways — rehabilitation and maintenance of structures. And because the demolition of buildings for new construction is regarded as a “bad development program,” projects to “repair” existing buildings can be found even in regions where reconstruction is unavoidable for 80% of the land area due to narrow roads and less than 0.1% of the land is covered by parks. Infrastructure development projects are rare, while home repairs, refurbishment of public areas (e.g., murals), and other improvements to existing physical environments are common in most areas.

However, it is doubtful that this approach would yield a “sustainable physical environment.” After all, if murals become an eyesore after regeneration projects are completed, the government would have to address this situation by developing more stopgap measures. And most importantly, questions remain on the impact of urban regeneration in improving the living condition of cities. There are reasons why it is considered a costly investment that “only creates murals.” ‘Fixing’ is not always the right answer. Urban regeneration and urban planning should fundamentally serve to create sustainable cities. However, because South Korea has undergone rapid urbanization without meticulous attention to the planning process, there are physical barriers that limit the effects of rehabilitation schemes on our cities.7)

The beautiful city of Paris was created from

19th-century urban redevelopment aspirations

In contrast, the complete dismantlement approach (or redevelopment) offers advantages of its own. Paris was able to transform itself into a city where both past and present coexist through redevelopment aspirations from the mid-19th century. How many people today remember Paris for its rotten stench, lack of access to sunlight, and its streets plagued with epidemics?

In that sense, renewal programs should be provided with the flexibility to use project models that are most appropriate for each region. For instance, cities that lack basic infrastructure, such as roads to accommodate fire trucks, could find it more favorable to implement redevelopment measures. We should not be portraying redevelopment and regeneration as binary oppositions like good and evil. Instead, we need to understand that redevelopment is a type of urban regeneration. Redevelopment itself is not “evil,” and we should work to expand its frameworks to enable a more comprehensive development. Ultimately, we must bear in mind that urban planning and urban regeneration should fundamentally strive to create a “sustainable city.”

1) Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport (2019) ‘National Urban Regeneration Basic Policy.’

2) Lee, Tae-Hee (2020) “Promoting private participation in urban regeneration projects: going beyond pump-priming” Construction & Economy Research Institute of Korea.

3) e.g.) Jeju economy (2020) “Asked for eco-friendly playgrounds, but… state project overlooks local needs.”

4) New daily biz (2020) “Changsin-dong shows interest in public redevelopment programs… the drive for redevelopment projects spark interest in Gangbuk district.”

5) Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport (2018) “Urban regeneration new deal project application guideline.”

6) Economy-based urban regeneration projects in Cheongju and Incheon faced the same controversies.

7) KBS (2018) “Regeneration versus Development versus Improvement… Mayoral candidates for Seoul and their solutions for housing challenges” May 28th, 2020.

This text was originally published on Yeosijae’s Korean homepage on September 8th, 2020.

< Copyright holder © TAEJAE FUTURE CONSENSUS INSTITUTE, Not available for redistribution >