Please join Yeosijae as we build a brighter future for Korea. Create your account to participate various events organized by Yeosijae.

- Insights

- |

- Global Order and Cooperation

- Future Industries

[Outlook 2021 ③ / CFR President Richard Haass] “It will be difficult for the U.S. to regain its global leadership... Power is in many more hands today.”

- 2021 will be the beginning of a slow, difficult, and incomplete recovery

- COVID-19 and renewing multilateralism should be our priorities

A fresh new year filled with uncertainties is upon us, and our world order still in shambles from COVID-19. Though the U.S. aspires to revive America’s leadership in the world, the capitol riot on January 6 has exposed America’s deepest divides. The Biden administration faces several pressing domestic policy challenges that must be addressed first to advance U.S. global leadership. Will Biden be able to demonstrate political leadership and lead divided America and the world? And what challenges will South Korea face in the future with Biden’s emphasis on allies and friends? The Future Consensus Institute (Yeosijae) sought out to understand the challenges faced by the Korean Peninsula and explore the future direction of South Korea through a series of interviews with Korean, American, Chinese, and Japanese scholars.

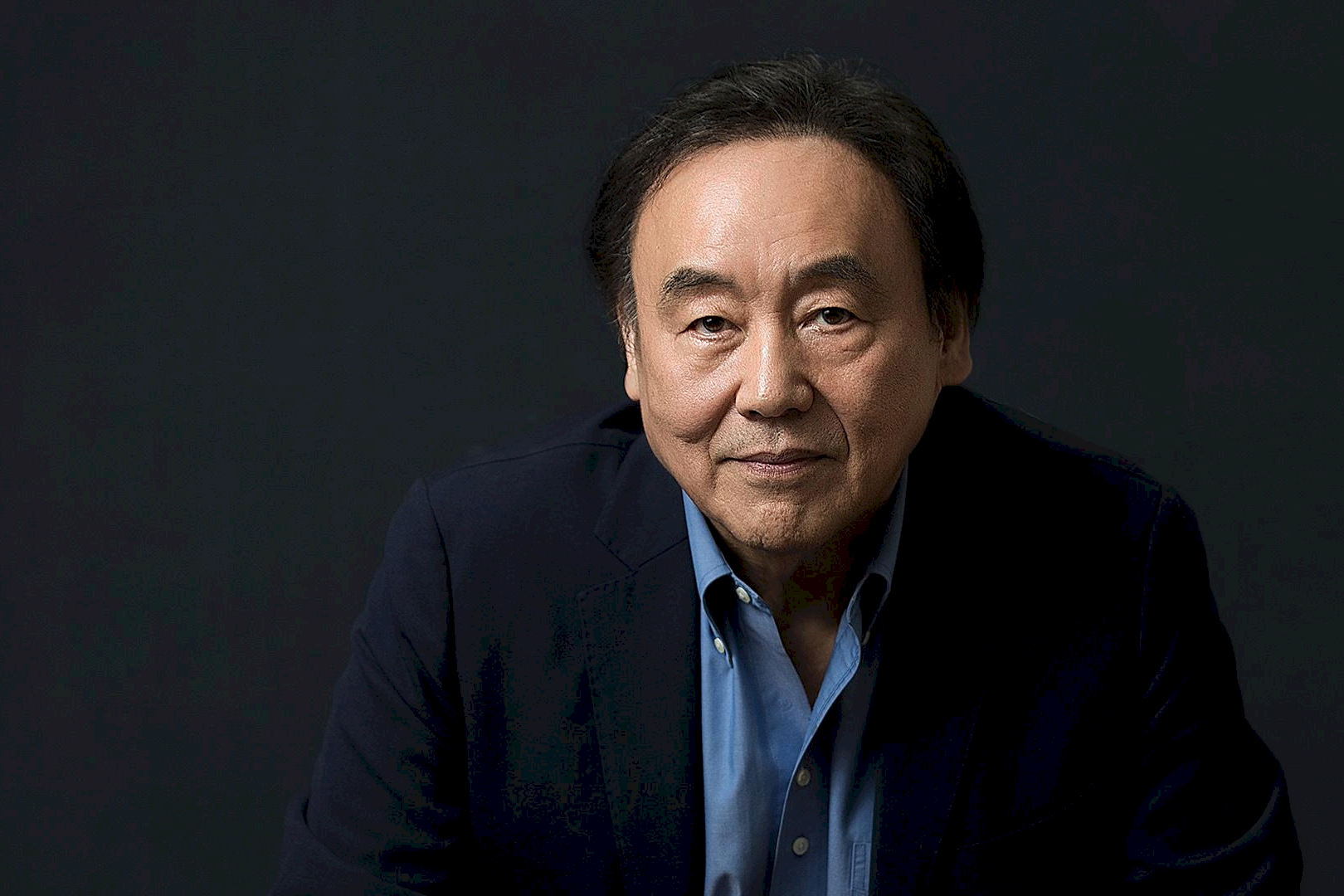

As the third part of our Outlook 2021 series, we spoke with the President of Council on Foreign Relations Richard Haass via videoconference. During the interview, Dr. Haass described 2021 as the beginning of a slow, difficult, and incomplete “recovery” and highlighted COVID-19 as Biden’s top priority in dealing with America’s biggest problems. Dr. Haass is a national security strategist with extensive government experience. He was a special assistant to President George H.W. Bush and senior director for Near East and South Asian affairs on the staff of the National Security Council. He became the President of CFR in 2003, and he has published many books on foreign policy strategies throughout his career. The interview was conducted by Yeosijae International Advisory Board Chair Won-Soo Kim.

Trump may be leaving, but Trumpism is not going away any time soon

The Capitol Riot shows the deep-seated anger in American society

Q. What will be the keyword for the U.S. and the world in 2021?

A. I think for the U.S. and the world, the central word for 2021 will likely be recovery. We will have our recovery from the pandemic, for the most part, and we will have an economic recovery. We will see improvement at least in those two ways in 2021.

But the recovery will be slow. It will be difficult, and it will be incomplete. In the U.S., hundreds and thousands of more people will die in 2021 from COVID-19. It will take a long time to get the economy back, and many jobs and businesses will never return. We have a long way to go.

Q. Biden will be sworn in on January 20, 2021. But looking at the January 6 Capitol Hill Riot, it looks like Trumpism is not going away any time soon. Growing frustration and dissatisfaction with America’s socio-economic system and the perceived inability of political establishments in handling the problems has given rise to the strong support for Trumpism. Taking this situation into account, what advice would you give to President Biden for his first year in office?

A. I think what the events at the capitol showed us is that we have some profound, deep-seated problems in American society. Mr. Trump—he stirs them up. He is an instigator. But he is also a reflection. He will leave the oval office, but he will not leave the political scene. He will have ways of having influence, and even if he were personally to leave the political scene, there are tons of millions of Americans who voted for him. There are tens and millions of Americans who believe that he won the election. As you have said, Trumpism continues to be a real problem for American society, and I do not think there is any simple or single solution there. I think what Mr. Trump represents, for many Americans, is a real grievance, a real anger that somehow, life is unfair and certain people have certain advantages that have been denied to them. And our political system, social media, cable television encourage radical voices. So when we deal with all these questions, 2021, at best, will be the beginning of a slow, long, difficult, uneven process of beginning to address the forces in American society that have led to a figure like Donald Trump having as much influence as he has had.

On the other hand, because of what just happened in the state of Georgia, Mr. Biden not only gets the White House but has Democratic majorities in both the Senate and the House of Representatives. And there are things he can do without getting congressional approval. He can get us back into the WHO or the Paris Climate talks if he wants to. He can reverse much of what Mr. Trump did through executive power. So I do not mean to suggest that there are not enormous difficulties ahead. There will be lots of political resistance because this is a divided country. But I still think there are some things Mr. Biden, as president, will be able to accomplish. He is never going to win over the 74 million people who supported Mr. Trump, but he can win over maybe 10 or 20 million of those. That would be potentially significant.

The U.S. will need to get its house back in order first

Before it talks about global leadership

Q. What are your thoughts about Biden’s efforts to revitalize multilateralism and restore America’s global leadership? Do you think it will be possible for Biden to make the U.S. a global leader again?

A. It will be extremely difficult. I think the instinct of the new administration will be multilateral—to consult with allies. But there are several problems. One is reputation. The image of the U.S. has been hurt in several ways. What happened on January 6, for example, understandably had an impact on how we are perceived. Our mishandling of COVID-19 has had a real impact as well. Many of the changes Mr. Trump introduced to foreign policy, even when those changes are reversed, will still have an impact because it suggests that American foreign policy is no longer consistent. If Mr. Biden changes things in the right direction, someone else could come along in four years and change things in the wrong direction. So I think it is going to be hard for the U.S. to regain its leadership for those reasons.

Second of all, Mr. Biden has the task of strengthening America’s economy and society. We need to have the resources, the political cohesion, and the willingness to act in the world. One of the problems he will face is that most Americans are going to say, “we have to focus at home.” Our domestic problems are so big we cannot do too much of that “foreign policy” sort of thing. Plus, the other challenge for American leadership has nothing to do with us. It has to do with China. It has to do with other countries. There are more competitors out there. This is not the world after the end of the Cold War, of 1945 and 1946, where the U.S. enjoyed tremendous advantages. This is a world where power is much more distributed. Power is in many more hands. So even if the U.S. gradually gets its house back in order, even if our economy and society recover, this is still a more difficult world to lead. That is just the reality. It is not about us. It is about the nature of the world and the third decade of the 21st Century. This is a more difficult time for anyone, including the U.S., to be an effective leader.

Domestic Policy Priority: COVID-19

Foreign Policy Priority: Multilateralism

Q. As you have said, the U.S. is facing many crises right now. So in your views, what issues should Biden prioritize in his first 100 days as President?

A. I think the single most important issue that needs to be a priority is dealing with COVID-19. We do not think of it as a national security issue, but it is a national security issue. It is central to our ability to get back to something normal because if we get the COVID situation gradually under control through vaccination, better testing, better therapeutic drugs, and more people wearing masks, the economy will improve. People will be able to get back to work, consumers will be able to shop, and kids will be able to go to school. I think that is the single most important initial priority.

Our most pressing priority in foreign policy is revitalizing our alliances. There is nothing in the world the U.S. can do better alone than it can do better with its allies, particularly in Asia and in Europe. So I would think multilateralism will be our priority in foreign policy. You asked me earlier what word I would use to describe 2021. If you asked me, “what is the word to describe Mr. Biden’s foreign policy in 2021?” I would have said multilateral. Multilateral implies we are involved in the world; that we are international. That we are not isolationists, but also that we are not unilateral. I think you will see the U.S. working with its partners and allies. Once we start to do that, it will give us a foundation to deal with China, Russia, North Korea, Iran, and all these other global challenges. We are much smarter if we do it with a basis of collective action.

The U.S. will choose to work with allies to put pressure on China to choose,

Instead of putting pressure on its allies to cut ties with China

Q. How do you see the future of U.S.-China relations? Bringing friends and allies closer to U.S. policy goals sounds like a good start for Biden, but it also raises the concern that it could put U.S. allies and friends in a difficult position amid intensifying U.S.-China rivalry.

A. One thing I will say is, it is going to be difficult. The U.S.-China relationship has deteriorated in recent years, and I do not see that changing any time soon. There will, therefore, be some areas of continuity between Mr. Trump and Mr. Biden. Less tweeting, but some continuity.

The American perception of China—Democrats and Republicans alike—has changed. Everybody is more skeptical of China, more critical, and more concerned about what China plans to do at home and abroad with its growing power. And there is a reason for that—it is called Xi Jinping. This is a very different China. This is much more repressive China at home. The hope that the government would reduce the state’s role in the economy is not happening. The state’s role in the economy is going to continue or even expand. China is building a much more capable military. Its diplomacy is often not diplomatic. So this is not Deng Xiao Ping’s China. This is a very different China. The people coming into senior jobs of the Biden administration understand that, and they share that view. So I think it is going to be a difficult period in U.S.-China relations.

That said, I do not think this administration will be as obsessed with bilateral trade agreements. I do not think the new Secretary of State will give speeches essentially calling for a regime change and end of the power of the Communist Party of China. I think you could see more criticism of human rights issues with the handling of Uyghurs and Hong Kong. I think you will see consistent concerns about Chinese pressure on the South China Sea or Taiwan and continued concerns about Chinese trade practices.

I do not think we are going to ask countries to choose. First of all, we are going to continue to trade with China. We are going to continue to talk with China. So if we are not going to shut down the relationship, we cannot ask anybody else to. That would be wrong, and it would be dumb. I do think you could face pressures on not sharing certain technologies with China, not allowing yourself to get dependent in certain ways with China.

Our relationship will continue to be a very complicated, very difficult relationship. But you will see more diplomacy between the U.S. and China. There will be less personal diplomacy and more intergovernmental diplomacy at senior levels.

But ultimately, China is going to have to decide what kind of a relationship it wants to have with the outside world. To what extent does China want to put pressure on its neighbors and force things, or to what extent is it willing to try to realize its aims in a manner that is acceptable and, potentially, even compromise some of those aims? That is up to China. So I think what we have to do is we have to make clear to China that certain type of actions will not be acceptable— that we will resist if China does certain kinds of things but that we are also open to a better relationship so long as it acts according to certain rules and certain restraints. Then, it is China’s choice to make. When you say, we should not force our allies to choose, what I think is, we should put pressure on China to choose instead. To choose what Chinese foreign policy is going to try to accomplish and how it is going to try to accomplish it. I think that is something we can try to influence.

“Foreign policy begins at home.”

Solving domestic issues will put real pressure on China

Q. Biden being a rule-based, value-based leader could present difficulties for the Chinese leadership. Dealing with Trump, who is more ad hoc, may have been easier for China compared to Biden and his principled, rule-based, value-based administration. How do you see the future of China?

A. I hope it does cause problems for the Chinese leadership. I want to force China to rethink some of its behaviors. That is what foreign policy is about. To me, foreign policy is about encouraging certain kinds of behavior and discouraging other kinds of behavior. So you will always have to think, what are your priorities, what tools do you have to bring.

So I think our goal, as in the U.S., South Korea, Japan, India, Australia, and other countries, should be to work together and try to come to an agreement on what Chinese behaviors do we want to discourage and what steps we have to take to discourage them. Then it is up to China to choose. I am a practical man. I think it is important that we have a good working relationship with China despite our differences. I am not naïve. I know we are going to have all sorts of differences. That is not the point. The question is, can we manage those differences in such a way that they do not spill over and lead to confrontation, in such a way that we can still cooperate on areas where our interests or aims overlap, say on North Korea or on the climate.

And if I add to this, I think if the U.S. does better, it will put real pressure on Xi Jinping and China. By not doing well on COVID, we made it easy on Xi Jinping. If we do better at dealing with our international challenges, then I think we show that a democratic capitalist system can perform in ways that top-heavy, communist systems like China’s cannot. But that is up to us. So I actually think, in some ways, the key to a better relationship with China begins here in the U.S. I once wrote a book years ago, about ten or eight years ago, called “Foreign Policy Begins at Home.” The foundation of a more successful foreign policy vis-à-vis China or with anyone else will be a strengthening of American society and our economy. I think Biden understands that. Understands that we cannot be effective in the world until we are more effective at home. So I think that will be a basic guiding principle of the administration of the 46th President.

The U.S. government should send a message to North Korea

Biden will relaunch “realistic diplomacy”

The U.S. and South Korea should be prepared to present a united front on the North Korea issue

Q. I want to ask a question about North Korea. The North Korea problem has been put on the backburner of the Biden administration due to a daunting number of domestic and international challenges. However, North Korea will not wait for the Biden administration to straighten things out, and it may just become the administration’s first foreign policy crisis. What will be your advice for the Biden administration on North Korea?

A. I think it could be one of the early foreign policy crises.

But first, we have a foreign policy decision to make about Russia, about extending the soon-to-expire nuclear arms control agreement – the so-called New START agreement. But the problem for the Biden administration is that we have to get the agreement extended, all the while we want to penalize Russia for the big hack they have done. So that is one challenge. The second one will be about what to do with Iran. Iran could actually be the first real big challenge of the new administration because Iran is increasingly moving beyond the limits of the 2015 nuclear agreement.

I would hope North Korea would be patient, but they may not be. What I would advocate is the new administration sending a message—a quiet message—to North Korea, telling them, “give us a little bit of time. Be patient.” In the U.S., the Federal Communications Commission mandates that every broadcast station has to announce what it is every so often. For example, they say, “it’s 12 o’clock, and welcome to NBC.” We call that station identification. And North Korea has its own idea of station identification. Every so often, it wants to make sure we have not forgotten who they are. “This is North Korea, and we do not think you are paying enough attention to us, so we are going to test missiles,” or something like that. I think it is quite possible (that North Korea could become one of Biden’s earliest foreign policy crises).

The new administration does not want a conflict with North Korea. But it does not want North Korea to keep going on its trajectory with more nuclear weapons and missiles. I think the new administration is a realist government. They are not going to be shouting denuclearization from the mountain tops. I think North Korea will remain a goal of U.S. policy, but a long-term goal. And I would bet that there will be some version of arms control with North Korea in the future, where American and North Korean diplomats try to work out some kind of arrangement. In exchange for that, North Korea could perhaps get some sanctions relief. Not all, but some. I think that is basically the path we will go down, with a degree of limits, a degree of monitoring, and sanctions relief. I think that is the most you could hope for.

It is important that the U.S. and South Korea tightly coordinate here—that we do not negotiate ourselves, but we present a united front. I think that is going to be the only realistic path. With COVID-19 and the global economic slowdown, North Korea might be open to something like this. The big question is whether Russia or China will cooperate, whether they will support or break sanctions. Regardless, my instinct would be to try to revive some type of diplomacy through the existing mechanisms of six countries or other multilateral diplomatic approaches.

I am also concerned about the conventional military situation on the Korean Peninsula. We cannot ignore the potential for terrible, damaging conflict on the Peninsula through non-nuclear means. So I think it is important that we find a way to address that as well. I do not know what the new administration is thinking on this, and it will probably take several months to develop, but at some point, you will see an attempt to relaunch what you might call “realistic diplomacy.”

Q. Cooperation of neighboring countries is also important in addressing the North Korea problem. Taking this into account, how do you see the future of South Korea-Japan relations? We often underestimate Japan, but it is an important player with leverage that can contribute to the negotiations with North Korea, so we cannot leave Japan out of the discussions on North Korea. The U.S. had always been a mediator between the two countries because we have a common threat and a common agenda to deal with, but recent developments have pushed South Korea-Japan relations to a new low. It seems like Biden could take some steps to restore South Korea-US-Japan relations in the early days of his presidency.

A. I agree. The developments in the last couple of days between South Korea and Japan are disturbing. It is really frustrating. As you have pointed out, the U.S. has been an intermediary between South Korea and Japan. But we have made a mistake by essentially no longer participating in this kind of diplomacy. But the people coming in, they believe in diplomacy. They believe in consultation, in alliances. They understand that we all lose if we do not coordinate and, in particular, if the relationship between South Korea and Japan deteriorates. So I would think there is a good chance what you are suggesting will be well-received.

Americans do not understand the world

We should teach Americans global literacy in our high schools and colleges

Q. The term “global literacy”¹⁾ stood out from your book “The World: A Brief Introduction.” In some ways, I think Biden is a person with high global literacy. But I also share the concern you raised about the apathy of American elites and the American public. How can we teach the young generation and the general public to be better informed and better educated about global affairs?

A: I want to first comment that Mr. Biden is extremely prepared for the job. He is probably the most prepared president on international issues since George H.W. Bush. I have known Mr. Biden since 1974, so he has been involved in these issues as long as I have. That means we are both getting old, but regardless, he is prepared for the job.

As you have pointed out, I am concerned about a lack of global understanding in the U.S., worry there is a lack of understanding about why the world matters. And I am worried that our lack of understanding feeds into isolationism, into people voting for presidents and ignoring their policy positions. When people voted this November, over a hundred fifty million Americans voted, but almost none of them voted based on the differences between Mr. Trump or Mr. Biden’s foreign policy, even though they were fundamentally different. And people do not understand why the world matters and how it affects our lives, even though 4,000 people are dying a day from a virus that began in China, even though climate change is affecting our weather, and even though terrorists trained in Afghanistan killed 3,000 people on 9.11.

So I would emphasize that we teach these ideas in our high schools and in our colleges. It is not enough that you go to Harvard or Stanford and take a course on the world or American politics and civics only if you want to take them. I want every high school students, I want every college students in America to understand their own country; because what January 6 tells us is, too many Americans do not understand their own democracy. Understand why it is special and what it takes to have a successful democracy. And clearly, too many Americans do not understand the world, how the world affects America, and how U.S. foreign policy affects the world. So what I would like to do is to try to change the curriculum in high schools and colleges to better prepare Americans to support and participate in American democracy and to be citizens that are supporting an intelligent foreign policy.

1) Global literacy is an understanding and the ability to express how the world is connected, what the current global issues are, and how they are changing. Richard Haass used this term in the introduction of his book, “The World: A Brief Introduction.”

This text was originally published on Yeosijae’s Korean homepage on January 19, 2021.

< Copyright holder © TAEJAE FUTURE CONSENSUS INSTITUTE, Not available for redistribution >