Please join Yeosijae as we build a brighter future for Korea. Create your account to participate various events organized by Yeosijae.

- Insights

- |

- Future Industries

- Next-Generation Values

Humanomics: A New Measure of Growth

Moving beyond GDP towards a more comprehensive measure… Focusing on individual growth and development

Hidden Perils of South Korea’s Remarkable Growth:

An Epidemic of Suicide and Anxiety

“Gold spoons,” “dirt spoons,” “i-saeng-mang (a Korean acronym for ‘This life is doomed.’).” These new terms with a cynical take on the world are starting to become everyday language in South Korea, depicting the anxieties and frustrations festering within our society.

cf. Spoon class theory

“Gold spoons” and “dirt spoons” come from the spoon class theory, which refers to the classification of individuals based on the assets and income level of their parents. People’s lives and their successes are, consequently, believed to be dictated by the wealth of their parents.

Having achieved both economic growth and democratization at the same time, South Korea is regarded as a relative success story. However, many South Koreans today are asking, “Why am I so unhappy even though we are prosperous as a nation?” and “why do I feel like I am falling behind when everyone on my social media feed or TV seems to be happy?”

Anxiety has always been regarded as a personal issue. The idea of “every-man-for-himself” has been the overriding mentality of our society for a long time. We may not have had the luxury to reflect on our anxieties due to the series of economic crises, accidents and incidents, pandemics, and societal changes that required our immediate attention. And over the years, with no governmental and social support, the number of people feeling isolated has gradually increased, and the drawbacks of the “every-man-for-himself” mentality have started to manifest in more ways than just “feelings.”

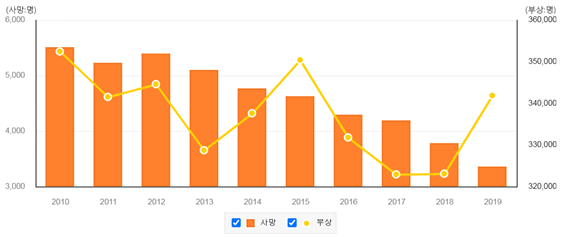

South Korea’s soaring suicide rate—one of the highest in the world— is a case in point. After a brief period of decline, suicide in South Korea is on the rise again. [Figure 1] Traffic fatalities, on the other hand, are on a steady decline. [Figure 2] Why do these trends look so different? Controlling traffic injuries and deaths involves changing people’s actions, not their perception; thus, regulation and enforcement (e.g., sobriety checkpoints) and investment (e.g., improving road infrastructure) can deliver results, to some extent. Suicides, on the other hand, deals more with the human mind, making it difficult to not only predict but also to prevent with the solutions mentioned above due to the multitude of influencing factors. If suicides result from extreme anxiety (due to the feelings of intense sadness, hopelessness, and anger), then it is a problem that cannot be addressed unless we tackle it at its roots by examining the factors that induce anxiety.

Anxiety in South Korea:

Risks factors for anxiety and their structural interrelations

To fully understand the issue at hand, we need to examine South Korean society’s anxiety from a systematic perspective. In particular, we need to understand the factors behind our concerns.

Sociology research reveals many new facts for our consideration. One important implication of the prevalence of anxiety among the general population is that it comes from not only factors related to personal issues and experiences but also politics, the economy, and society. Jae-Yeol Lee and Jin-Sung Jung (2010) have highlighted the systematic relations between anxiety and various risk factors within our social system.

risk politics. Seoul: Seoul National University Publishing Culture Center Kweon-Jung Cho. (2014) ‘Is Seoul Safe’

Diagnosing anxiety in society and its social treatments, Seoul Institute. Recited from p. 10)

Empirical research also reveals that anxiety is related to various social risk factors. The Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA) has presented a big data analysis on the factors associated with anxiety and their structural interrelations.1)

[Table 1] lists the keywords that have most frequently appeared with anxiety in news articles published in 2007, 2015, and 2018. As Jae-Yeol Lee and Jin-Sung Jung have pointed out in their research, big data analysis shows that anxiety is linked to a myriad of factors ranging from politics to economy and society.

Big data analysis revealed

Increasing prevalence of political and policy-related keywords

If we examine the results from 2018, anxiety was typically associated with terms related to politics, economy, and society. Economic keywords that made the list were as commonly expected: finance, real estate, stock prices, policy, and investment. Interestingly, the terms “president” and “government” appeared on news articles with a relatively high frequency. Moreover, it is worth noting that terms related to politics and policies were increasingly associated with anxiety in recent years.

and 2018. (Source: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. 2019. ‘Social Anxiety and Social

Security in South Korea’ – A Qualitative Study on Social Anxiety. p.114)

Anxiety and macro-systemic factors:

Anxiety levels are heavily affected by factors such as real estate and stock markets

The big data analysis sheds light on few factors to consider regarding social risk factors. First, while anxiety is a personal experience, its influencing factors are closely associated with macro-systemic factors. Surprisingly, personal anxiety struggles are closely connected to not only the areas of politics and society but also to the economy, financial market, and government policy. This means that it is becoming more common for socio-economic changes and policy shifts to create new personal anxieties or an anticipatory sense of one. Increased public interest in real estate (homeownership dream), the stock market (wealth management), interest rates (opportunities of loans), and other factors, in particular, suggest that these variables are the biggest areas of concern for the general public.

Rising expectations of government and

the increasing significance of political and policy-related keywords

Second, political and policy-related keywords have appeared on news articles with anxiety on many occasions and are appearing more frequently in recent years. There are two ways to interpret this growing trend. One, as KIHASA points out, is that it shows that the public has high expectations of the government to lessen their anxiety. People are more interested in political and policy-related keywords because their expectations are high. On the other hand, it could also mean that political, economic, and social systems have failed to relieve the public’s anxiety. In other words, people are more anxious because the system is not working.

So how do these risk factors relate to one another? A network analysis of the keywords could be used to understand their interrelations. Though the research does not reveal a clear-cut cause-effect relationship, it identifies the core members of the network and the intensity of the relationship between them.

‘Social Anxiety and Social Security in South Korea’ – A Qualitative Study on Social Anxiety. p.129. Modified and recited.)

[Figure 5] is a network analysis of the keywords presented by KIHASA.

Key components of the Keyword Network Analysis:

Market, President, Government, Finance, and Interest Rates

Keywords most commonly associated with anxiety in the media were: the market, president, government, finance, and interest rates. Surrounding the term “president” were the terms government, housing, stock prices, interest rates, and finance, which shared close connections with “employment opportunities” and “minimum wage.” The diagram shows that the causes of personal anxiety (or employment and income) are closely related to macro-systemic factors of economic condition and economic policy. Though we cannot draw a conclusive cause-effect relationship from the analysis, it still is an indication of our subjective understanding of the strong association between anxiety caused by employment or income and macro-policy factors (the implementation, modification, and changes of policies).

Much like the word frequency analysis, the network analysis helps us deepen our understanding of anxiety. Some parts of the diagram defy expectations. To think that the word “president” would be the most influential member of the network! Even for a president-centered country like South Korea, it would be difficult to foresee that the word “president” could be at the heart of our anxieties.

The results also indicate that South Koreans are sensitive to macroeconomic changes. The diagram shows that Koreans are keen on finance, interest rates, stock prices, real estate, and other macroeconomic issues—even considering that the study examines only news articles, as it had been with the term “president.”

Mounting Anxiety:

Anxiety casts a shadow over even the relatively affluent households

Anxiety is commonly associated with poverty. People would certainly be anxious when food and other basic necessities of life are scarce and there is little hope for the future. However, the poor are not the only ones suffering. Those that are more financially stable share the same sense of uneasiness. In the conclusion of their study, KIHASA wrote, “The levels of life satisfaction, happiness, and optimism are unrelated to the levels of social anxiety. In South Korea, there are many that feel anxious, despite their high levels of economic security and happiness.” They presented the results of surveys on “permanent employees,” who are considered to have a relatively stable life compared to others, and their anxiety levels as evidence.2)

“I may be a permanent employee, but there are no guarantees that I will not be laid off in the future…. I have to study for certification exams to prepare myself for a new job just in case I have to switch jobs, but the rigid, old workplace culture keeps me in the office for almost 12 hours every day. My commute hours are long, so there is no time for me to study. And with my superiors giving out warnings that I could be fired at will even if I am a permanent employee, I feel anxious.”

“I work in the future technology sector—a sector in which South Korea is yet to establish a firm foothold. Things are bound to change in the future, and I have no option of lifetime employment, so I have some concerns about how I will take care of myself and my family in the future. I am very much interested in real estate investments, but housing prices are soaring, and I do not know how things will change in the future, so I am anxious all the time. …. It upsets me that I cannot change things for the better—that I can only accept things as they happen.”

“After moving to Seoul and getting a permanent job, I thought I should live like others—that I conform to social norms and work at one place for a long time to build my career. And that got me comparing myself with my friends, who achieve traditional milestones at certain points of their life, and it triggers my anxieties.”

Changes After the Asian Financial Crisis:

The rise of the “every man for himself” mentality

KIHASA pointed out that anxiety in South Korea is handled on a personal level and that social support and assistance are minimal. Anxiety, in other words, is considered to be an individual experience that should be addressed personally. The lack of systematic support for anxiety, inversely, becomes a risk factor that exacerbates the issue. KIHASA believed that the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis was what paved the way for the “every-man-for-himself” mentality to become the bedrock of our society.

The Post-COVID-19 era: A time of change that brings with it

the threat of increased social anxiety

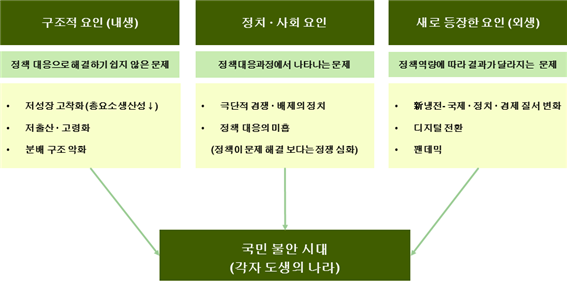

Various factors that could further increase our anxiety are emerging today. [Figure 6] lists them under three separate categories: structural, political, and new.

(From left) Structural issues: sustained low growth (total factor productivity↓),

low fertility/population aging, flawed wealth distribution system

Sociopolitical issues: cut-throat competition/politics of exclusion, policy shortfalls

(the tendency of policies to exacerbate the political divide instead of reducing problems)

New issues: the New Cold War/changes in the international, political,

and economic order, digital transformation, the pandemic

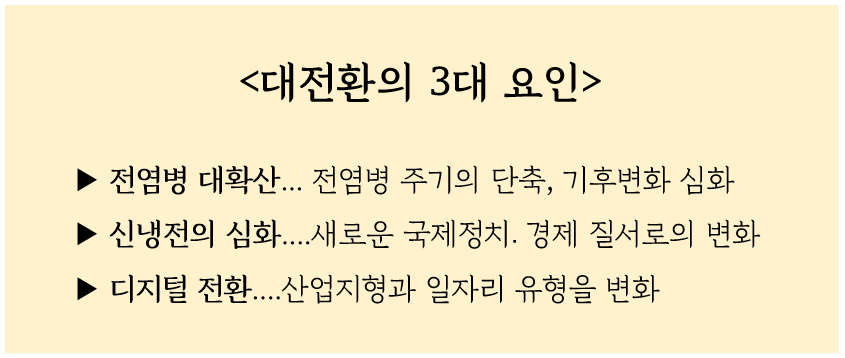

Complex risk factors that could shape people’s lives and countries’ fates have started to appear as well, signaling that the age of Great Transformation is upon us.

1. The COVID-19 pandemic: shortened intervals between pandemics, exacerbated climate crisis

2. Intensified New Cold War: a transition into a new political and economic order

3. Digital transformation: changing industry landscapes and jobs

The three drivers of the Great Transformation present not only significant risks for our economy but many opportunities as well.3) If we successfully contain the pandemic and handle its subsequent downside risks, we could elevate our economy and our brand on the global stage. Digital transformation could also be a chance for South Korea to generate a new growth momentum. The positive synergy between the coronavirus crisis and the digital economy foreshadows the growth of the contactless/digital economy. These economic changes are occurring at a rapid pace, much beyond our expectations. If we prepare ourselves well and seize the opportunities before us, our successes will be more than enough to build a new foundation for economic growth.

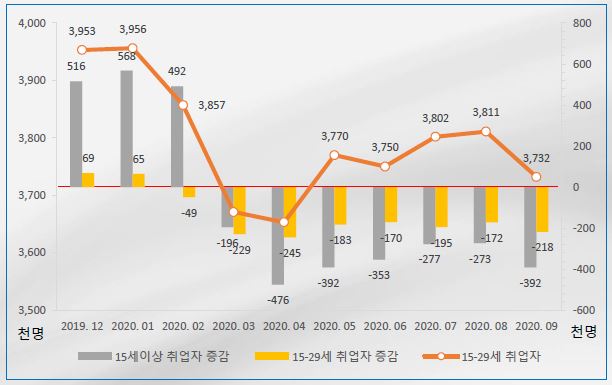

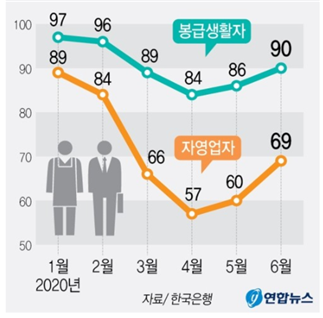

However, if we examine these changes from anxiety perspectives, these factors could also create disruptions in our lives, increase uncertainty, and exacerbate the anxiety issue. The economic slowdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic is trapping people in financial hardships. The fallout of the pandemic has and is hitting the jobs of the most vulnerable people first and the hardest. Youth employment has been particularly affected [Figure 7], and social distancing measures have directly impacted small businesses. [Figure 8]

(monthly; the grey bar represents the increases and decreases in youth employment

for 15 years old and above, yellow bar for 15-29 years, and the orange line

for the overall trend for 15-29-year-olds) (Source: Yoo-Bin Kim. 2020.12.8.

‘Pre- and post-COVID pandemic trends of youth employment and policy directions.’

Korea Labor Institute.)

between the self-employed (in orange)

and wage earners (in blue) in 2020

(Source: Yonhap news 2020.7.27)

Broad changes to come in the post-COVID era:

“Disruptions” will lead to increased feelings of anxiety on individual levels

Moreover, as the pace of change accelerates, the difference in the rate of change between individuals and society will increase and become more varied. If we consider the results of the studies mentioned above, it is not difficult to conclude that disruptions will affect our personal lives more dramatically in the days to come and that it will subsequently lead to more anxiety.

It has also become more likely for the relatively affluent population to experience more anxiety from rapid, broad-scale socio-economic changes. The post-COVID-19 era promises radical changes for traditional industries and jobs. With the exception of the people who already have the technological competencies and opportunities needed to adjust to the new landscape, everyone will be subject to anxiety.

Inherent structural problems (low growth, population aging, declining wealth distribution system)

will create more anxiety in South Korea

In addition to the new challenges, there are deeply entrenched structural issues to consider. They are: prolonged low growth (falling potential growth rate), low fertility and population aging, and a failing wealth distribution system. These are problems that cannot be addressed in the short term because they stem from structural shortcomings. Some of these factors, as the studies above show, are already causing anxiety in South Korea. As these issues interact with the new challenges of the post-COVID world, they will exacerbate the anxiety issue in South Korea.

There is more to consider on this account. The third category of factors consists of those that, in some ways, could increase our anxiety even further, and it deals with our capacity to respond to the other risks mentioned above (new and structural). Our third challenge comes from our politics and policies.

Policies are the embodiments of our ‘values’;

Creating policies that are in tune with the times

Our policies are the embodiments of our values. They are more than just matters of academic discipline or theories — they uphold certain values depending on our political direction. Policies, therefore, contain more than just logical consistency. From a policymaking perspective, theories are tools to bring our values to life, and politics is the process of developing such policies—the process of discovering the best ways to serve people’s interests (or their value). The productivity of politics, therefore, depends on how policies effectively capture our values.

Does South Korea’s politics fulfill this role? I doubt that people would see it in such a positive light. Instead, it would be more appropriate to say that people believe politics is becoming less and less of the “negotiation process” to build timely policies. Rather than solving our problems, our policies are increasingly becoming the “seeds” of political disputes that undermine the process. The frequency and the density of political keywords in the diagrams above could be interpreted as indications of this skepticism. After all, it would be difficult to hold a country’s politics in high regard when it overlooks the needs of its people.

Social Anxiety:

Our new “zeitgeist”

With the research that has revealed that anxiety is a social phenomenon caused by various structural and social issues (ranging from politics to economics and policies), it is easy to see that changes in the post-COVID era could induce further anxiety in society. Moreover, new challenges and structural and policymaking shortcomings could generate a synergy that could further exacerbate the situation.

The fact that anxiety is becoming a social phenomenon suggests that it is an issue that has to be addressed as a challenge of a new era. In other words, “people’s concerns for survival and growth” are becoming the “zeitgeist” or the “spirit of our times.” Since this is not a problem for individuals to tackle on their own, it would require a comprehensive governmental response in some form or another; thus, our national vision should also evolve to maximize government efforts.

Building a world where ‘people can live a full life’…

Focusing on individual growth and development

For our new vision, I would like to propose that we set our goals on building “a world where people can live a full life” or “a country that everyone wants to live in” to demonstrate our commitment to resolving the anxiety issue and promoting individual growth and development.

Creating “a world where people can live a full life” refers to a commitment to build a country and a society that not only dissolves personal anxiety but also supports personal growth and development, regardless of structural risks and uncertainty posed by socio-economic changes. Social intervention and support for personal growth and development are necessary because the breadth and speed of change and the qualitative and quantitative properties of risks are evolving beyond individuals’ control. After all, what could an individual do against the anxieties and risks posed by the COVID-19 crisis, economic recession, and digital transformation? The new vision will indicate a shift in our society and our country, away from the “every man for himself” mentality to a “common goal-oriented” one.

Building “a country that everyone wants to live in” means we will improve the quality of life in South Korea to make a country that is better to live in than others. With the rise of the contactless/online economy, borders are becoming less relevant. People today have more options to choose from than just “immigration” or “foreign investment” when selecting their desired countries. Through the digital world, individuals can now reside in one country and conduct their activities in another. If we adequately combine the traditional offline methods with the online ones, people will be able to choose their destination countries at a lower cost and in a shorter period.

Once it becomes easier for people to choose, social anxiety will start affecting countries’ long-term competitiveness. Considering that individuals have different capacities to choose where they live (those with higher income levels and digital competency have more options), countries with high anxiety levels will not be able to retain high-skilled individuals within their borders over the long haul. States performing better in dealing with the nation’s anxiety levels, on the other hand, will attract not only those residing within their physical borders but also those living beyond and across the world. In essence, a nation’s ability to manage social anxiety is closely related to its long-term competitiveness or “systematic competitiveness.”

The more South Korea is regarded as a favorable environment for personal growth, development, and children, the more competitive it will be as a nation. There is no doubt that a country that best attracts talent and capital holds an advantage in achieving quantitative and qualitative growth. Thus with this understanding, I offer the vision of “a country that everyone wants to live in” as our national vision.

The anxiety issue requires comprehensive policy responses

that go beyond the limited scope of “social policy”

The anxiety issue intersects with socio-structural risks in many ways. Its strong ties with macro-level factors such as politics, economy, and policymaking, particularly suggest that it is not a matter that should be dealt with within the limited scope of “social policy.”

Moreover, our shortcomings in addressing and delivering results for socio-structural risks that have evolved over the years imply that we need a radical change in our approach.

Furthermore, to develop a system that not only reduces anxiety in society but also actively supports individual growth and development, we need not only social policy but also comprehensive political and economic policy efforts. This suggests that we need to take a fresh and holistic perspective on government policies on anxiety.

Introducing a new economic philosophy:

Integrating economic and social policy

As stated, our economic policies should now extend beyond the limits of complementary measures that emphasize the welfare aspects of policies to promote an active integration of social and economic policies. This means setting “personal growth and development” as the priorities of economic policies. Consequently, our new economic philosophy should be “Humanomics.”

What does it mean when an economic philosophy focuses on the integration of economic and social policies? It means that we develop our policies by examining how economic, social, and political issues affect our lives (or the seven components of life—job, income, housing, health, safety, community, and value).

This reflects the findings of the research that we examined above. As the big data analysis shows, there is a strong connection between macro-level issues (of politics, economy, society, and policy) and individuals (or people’s jobs, income, housing, health, safety, community, and value.) Humanomics, our new philosophy, focuses on this relationship from the early stages of policy development, assesses its impact, and formulate solutions based on the results. Developing policy on employment, for instance, would involve an assessment of factors (such as the COVID-19 pandemic, U.S.-China relations, and climate change) on not only individual levels but also on holistic, comprehensive levels (such as job creation or innovation and employment protection or inclusion).

The idea behind Humanomics is not something new. Policies, in some aspects, have always been developed in this manner. However, Humanomics is different from other philosophies in that it explicitly outlines these aspects and presents them as standards for policy decisions.

Economic policies can use or combine a different set of policy tools even for the same goal. And depending on the approach they take, the level of resources invested will vary. If Humanomics establish individuals’ life as the standard for policy formulation and decision making, it will give rise to a new set of policy tools and investments. In this regard, an economic philosophy will not just be a “political motto” but a determinant of policy content and implementation.

Humanomics:

An embodiment of our desires for the new era

There are no assurances for long-term growth for any country that is incapable of meeting the people’s needs. South Korea is one of the few “success stories” that has managed to develop its economy and democratized its political system. But overall, and with some exceptions, our success has not facilitated growth, development, and happiness for individuals. People, who had worked tirelessly in the hopes of a better tomorrow back when the survival of the nation was at stake, have been left to fend for themselves upon retirement. Though our economy has doubled in size over the years, little has changed about the people’s circumstances. Workers that have been thrust into the society at this time of great national crisis live in fear of reduced job opportunities. Worried about their future, they have turned to civil service exams and other activities to pad their CVs, further isolating themselves from others.

No society with an epidemic of anxiety that spans across generations and social classes can promote healthy, sustainable long-term growth and development. With a system that repeatedly makes empty promises of tomorrow when more people are concerned about their todays, South Korea could be headed for a tragic catastrophe.

It is time for us to start caring about people’s anxieties — the time for the government and society to take an interest in people’s quality of life. “A World for the People” vision marked the beginning of this transition. Now, we must work to build a “world where people can live a full life.” I believe this is our zeitgeist – the need to care for people’s lives. Humanomics is an economic philosophy that identifies personal growth and development as the top priorities of politics and economic policies; thereby, it is the embodiment of our zeitgeist.

[References]

1) Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. 2019. ‘Social Anxiety and Social Security in South Korea’ – A Qualitative Study on Social Anxiety.)

2) Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. 2019. ‘Social Anxiety and Social Security in South Korea’ – A Qualitative Study on Social Anxiety.) p. 163-7

3) Byoung-Jo Chun. 2020.8. ‘World economy rankings will look completely different in the post-COVID-19 era’. Yeosijae Insight.

|

Byoung-Jo Chun graduated from the Department of Economics at Seoul National University and received his Ph.D. in Economics from the University of Iowa. He was an economic advisor, an economist at the Asian Development Bank (ADB), and the President of KB Securities. He currently is a Distinguished Fellow at the Future Consensus Institute (Yeosijae). |

< Copyright holder © TAEJAE FUTURE CONSENSUS INSTITUTE, Not available for redistribution >