Please join Yeosijae as we build a brighter future for Korea. Create your account to participate various events organized by Yeosijae.

- Insights

- |

- Digital Society

- Next-Generation Values

The Changing Landscape of Work: Reskilling and Upskilling the Workforce

- Inspiring employees to learn new skills (reskilling) and deepen existing ones (upskilling)

- Harnessing the power of artificial intelligence for continuous, personalized, lifelong learning

A woman sits at a kitchen table, puts on a virtual reality (VR) headset, and waves her hand in the air. Though there is no physical monitor nor a keyboard in sight, she works—on her virtual office space. She continues working, uninterrupted, as she moves to her attic then her bedroom with a VR headset. This was a scene from a clip showing Facebook’s “Infinite Office,” which was released last year. In recent interviews with media outlets, Mike Schroepfer, Facebook’s CTO who oversees the organization’s technologies, said, “working from home with two-dimensional screens like laptops can be difficult.” He predicted that we “will see virtual offices, which utilize VR technologies to enable a more natural communication, take off in the near future.”

Though we have just recently transitioned to telework with COVID-19 giving rise to remote work, people are already looking ahead to the world of virtual offices. By thrusting the world into a “contact-free” era and forcing people to be more open to technological change, the pandemic has significantly accelerated the changes of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Consequently, what seemed like a “distant future” has now become our reality “today.” In the face of shifting paradigms, even the world of work—or the way we work and the way employment is structured – is no exception to the changes brought on by the pandemic. Even the use of a virtual office is no longer confined to sci-fi movies. As Facebook’s CTO predicts, the world of work – from our workplaces to the way we work— will be profoundly different in the near future.

Will our future be as rosy as the video envisions? There are some clouds ahead for the future—the possibility of humans being left behind by rapid technological advancements—that we must not overlook, and this brings us to our question: Are individuals and businesses prepared for the future of work and the workplace?

World Economic Forum: The Future of Jobs Report 2018

“Skills needed for jobs are changing rapidly”

“The Future of Jobs Report 2018” is a report published by the World Economic Forum that examines from various angles the changes that the Fourth Industrial Revolution bring to the future of work and workplaces. The report, in particular, predicts changes for the 2018-2022 period for work and employment structure and offers recommendations on how individuals, businesses, and governments could respond and prepare for the changes ahead and foster future talent.

WEF’s report presents two scenarios for the future of work. The first is an optimistic scenario, where governments, businesses, and individuals have effectively responded to the changes and have come out on top with better jobs, increased productivity, and subsequently, a better quality of life. The other is a grim picture of the future—one where people that are not equipped with the necessary skills lose jobs to artificial intelligence, and polarization grows.

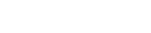

The report points to robots and automation as key variables affecting the future of work. [Figure 1] In 2018, 71% of total task hours across the industries covered by the report were performed by humans, whereas machines accounted for 29% of the work. But in 2022, 58% of the work is projected to be carried out by humans and 42% by machines. By 2025, machines will outstrip humans in contributions, with 52% of the work hours performed by machines compared to 48% by humans.

Another important variable is the dramatic shift in skills requirements brought on by digital transformation. The average skills stability, which refers to the proportion of core skills required to perform a job that will remain the same, is expected to be about 58% in 2022. This means that 42% of the skills needed to perform most jobs will change in 2022. In other words, many of the technologies and skills that are our bread and butter today will become obsolete in a mere one to two years. We are, in essence, living in an era where the rate of change is so fast that technologies become obsolete faster than they can be integrated into society.

Human workers are increasingly losing ground in South Korea,

where robots have been implemented on a wide scale

A study of CEOs from companies around the world conducted by the IBM Institute for Business Value (IBV) has found that as many as 120 million workers in the world’s largest 12 economies may need to be “retrained or reskilled” as a result of AI and automation, and estimated up to 60 million workers might be “reduced or redeployed” to other roles in the next three years.

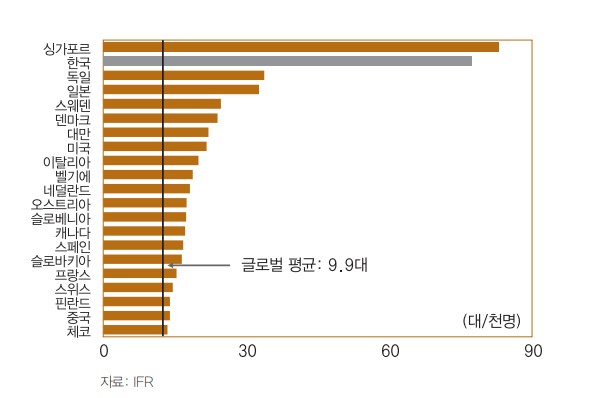

The trend of robots replacing humans in the workplace is even more pronounced in South Korea, a country with high robot density (or the number of robots per 10,000 workers). According to “The Impact of Industrial Automation on Employment” report (2021) published by the Bank of Korea, the number of industrial robots in use has sharply increased in South Korea since the 2008 global financial crisis. Moreover, the findings revealed that the increasing adoption of robots in business has, subsequently, reduced employment opportunities for traditional (or human) workers and has slowed real wage growth.

Between the 2000-2007 and 2010-2018 period, the number of robots sold in South Korea jumped over four times from 7,000 units to a yearly average of 30,000 units. The country had the second-highest robot density in the world in 2018, with a staggering 85.5 robots per 10,000 workers, compared to the global average of 9.9 units per 10,000 employees. The average annual growth rate of robot density has also accelerated since the global financial crisis, from an average increase of 1.26 units in the 2000-2007 period to 5.28 units in the 2010-2018 period, significantly higher than the growth rate of Japan (0.07->0.12) and the U.S. (0.9->0.93).

The report explained that this was possible because South Korea’s manufacturing sector is comprised of electric and electronics (32.2%), chemical (15.4%), transportation (11%), and machinery equipment (9.1%), which are industries with high volumes of relatively simple tasks that provide favorable conditions for automation.

Though robot adoption could positively affect productivity and cost-efficiency, for workers on the field, an accelerated pace of automation is not the most welcoming trend. According to a study of the relations between robot penetration (robots per 1,000 workers) and the growth in the number of workers and real-wage (using data from 2010-2018), employment and real-wage gains suffered losses of 0.11-0.12% and 0.27-0.29%, respectively, each time robot penetration levels increased.

The research, however, noted that it had considered only the impact of robots on employment in selected industries and that further research is needed to examine its positive effects, including its impact on productivity growth and on the creation of new industries. Moreover, it added, “Since robot distribution is expected to gain further steam as digital transformation accelerates in the post-COVID-19 world, it is necessary to promote the development of high-value-added industries and simultaneously, increase labor mobility across sectors as we move forward.”

Organizations are doubling-down on their efforts to attract the talent they need;

We need to expand beyond traditional hiring processes and training strategies

Though digital transformation is threatening the jobs of individuals, companies, ironically, are struggling to find the talent they need. The lack of available talent has been identified as one of the biggest risks facing organizations. In other words, today, there is a public outcry over the loss of jobs on one end and the lack of available talent on the other. What has brought on this paradoxical situation? The answer, is not because there is a “shortage of talent,” but because there is a shortage of “people who have the skills that companies need in the face of a new economic paradigm.”

As we have examined earlier with the WEF’s report, 42% of the core skills required to perform existing jobs are expected to change between 2018 and 2022. Companies are finding it increasingly difficult to acquire the talent they need. [Figure 3] The ManpowerGroup’s 2018 Talent Shortage Survey found that 45% of employers were struggling to find the skills they need and that it was higher for large organizations, with 67% reporting talent shortages in 2018.

The term “skills gap” is used to describe the difference between the skills that employers need and the skills that workers actually possess, and due to the rapid development of technology, this gap is widening fast. In an effort to reduce the gap, people have turned to “reskilling” and “upskilling” as a solution. “Reskilling” refers to the process of learning new skills for a new role, and “upskilling” refers to the process of learning new skills that enhance employee performance.

Reskilling and upskilling of the workforce has been an integral part of the business agenda for Fortune 500 companies over the last several years. Many businesses have committed to a goal of reskilling or upskilling more than half of their employees by 2025. There is a general consensus on the need for additional education. However, the strategies and the means to get there are yet to be agreed upon.

Companies, as a result, are still relying on new hires to fill the gaps instead of reskilling or upskilling their current workers. IBM Institute for Business Value’s global survey of human resources (HR) executives also showed that most executives still depend on the hiring process to mitigate the skills gap. It also revealed that they fear that it may not be enough to close the skills gap in the future if technological advancements continue at the rate of growth that we have now.

Employers point to the lack of cost-benefit analysis as one of the main reasons why they are struggling to formulate a strategy to retrain their workforce. Though the data remains insufficient, organizations have started to invest in case studies and empirical research on real-world applications of new strategies in recent years. As part of the growing trend, the WEF conducted a cost-benefit analysis of reskilling from both business and government perspectives with a big-data approach and discovered that roughly 25% of all workers expected to be displaced by technology could be reskilled into a new position with a positive cost-benefit balance for companies, while the same held true for 77% of workers from the government’s perspective. This indicates that if we tap into public-private partnerships as part of our reskilling strategy, we could better prepare ourselves for what is to come in the future of work.

Workers are eager to learn;

Employees, employers, and the government should work together to respond to the changes afoot

Another encouraging sign for reskilling and upskilling the workforce is that workers recognize the need to develop their skills and are eager to learn. In collaboration with the Boston Consulting Group (BCG), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) published “Automation, Skills and the Future of Work: What do Workers Think?” report in 2019, covering a survey that was conducted on 11,000 workers in 11 countries (the U.S., the U.K., Germany, France, Spain, Sweden, Japan, India, Indonesia, China, and Brazil). The survey excluded highly-educated workers to focus on understanding the perceptions of middle-skilled workers and less educated and lower-income workers on the future of work.

It found that workers that are older, poorer, and exposed to job volatility were more likely to have negative perceptions about how artificial intelligence and automation will affect the future of work. Furthermore, respondents from countries with higher levels of robot penetration were more concerned about the future of work than those from countries with lower levels of automation.

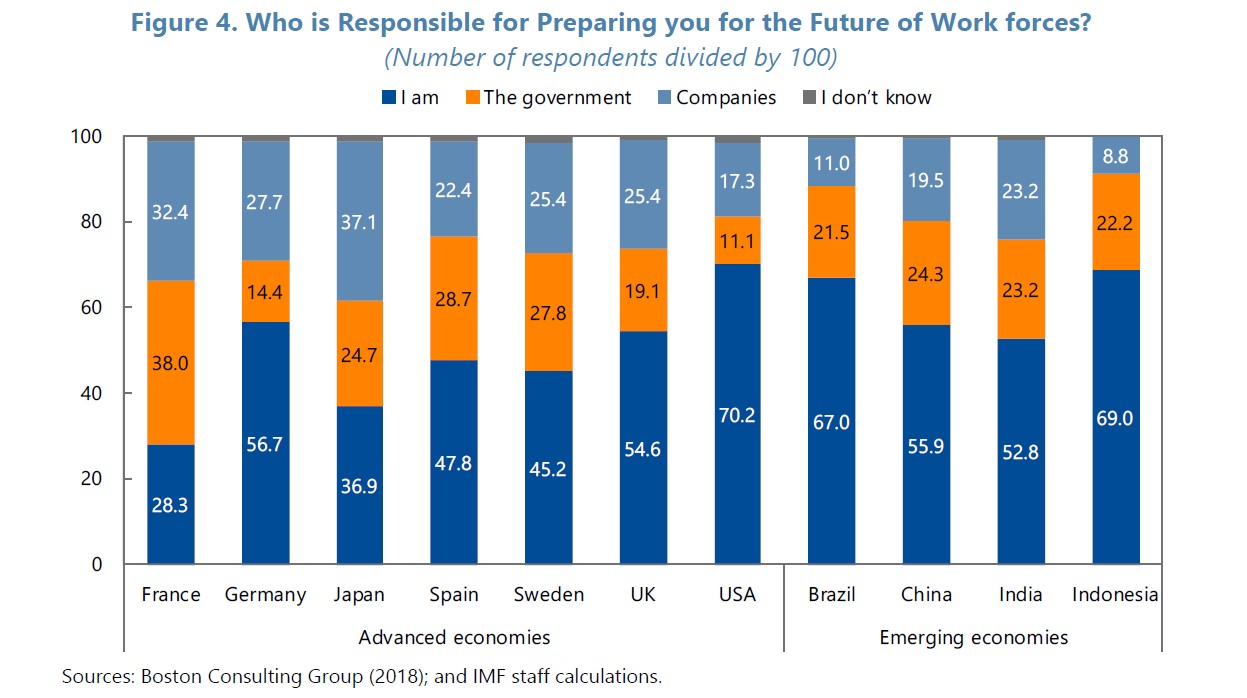

However, regardless of their perceptions, many workers considered themselves as first responsible to prepare for the future of work. [Figure 4] With the exception of the U.S., workers in advanced economies also believed that companies should play a leading role, and in countries like Spain and Sweden, respondents held governments responsible as well. However, workers with positive perceptions of the future of work were more likely to recognize the need for re-education and retraining to adapt to rapidly evolving skills demands.

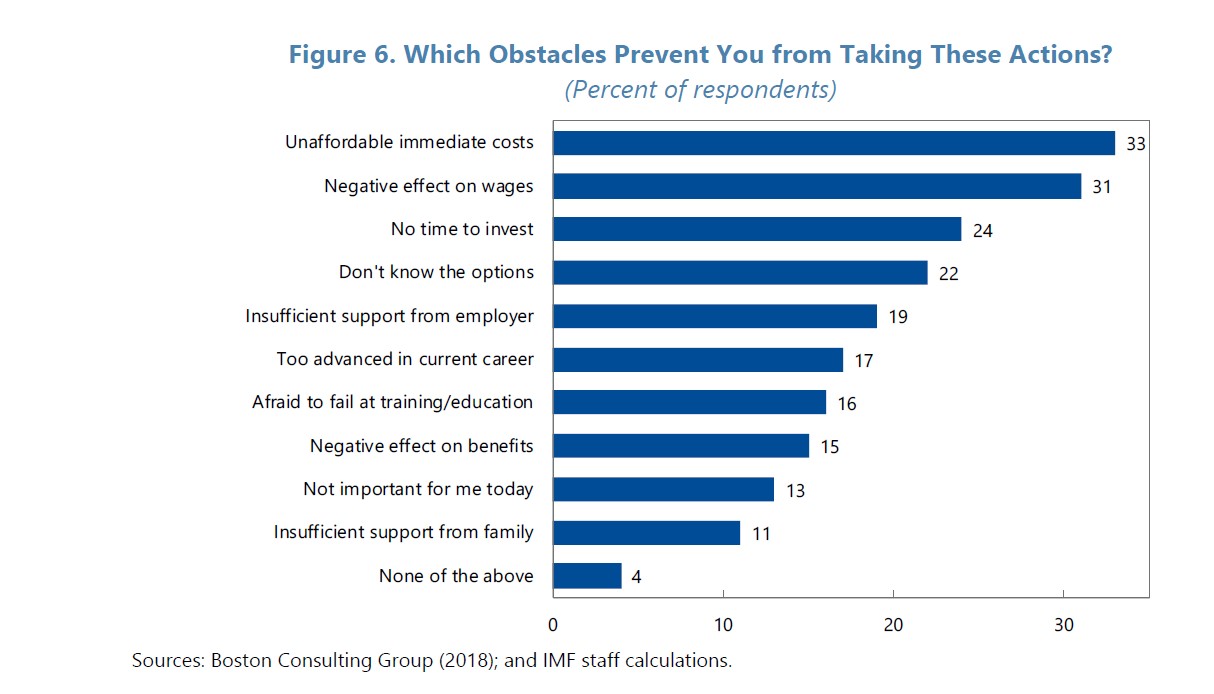

Financial constraints provided to be the biggest hurdle for workers seeking additional training. [Figure 5] Lack of time was also highlighted as an obstacle, suggesting that if the government and private sector provide financial support and invest in re-education programs, and if businesses provide various programs within their organizations for workforce development, we could substantially mitigate the impact of digital transformation on our jobs.

Harnessing the power of artificial intelligence for personalized education

What ultimately drives innovation are humans. To ensure future competitiveness, private sector organizations are investing in programs that teach workers how to develop new skills (reskilling) and perform better (upskilling). These programs teach skills that are not just limited to the employee’s scope of work, but those that also help them find a new job, communicate in the Fourth Industrial Revolution era, and build digital literacy.

For retraining programs to be effective, personalized education is a must. Providing education to employees in traditional terms meant bringing employees performing similar jobs into a room to listen to the same content. However, this is no longer an effective form of education. Just as people expect a personalized experience from search engines and online stores, people expect a personal experience that reflects their individual experiences, goals, and interests from education programs. Companies can no longer attain competitive edges in this rapidly changing environment through “en masse” training programs. Now, it is more imperative that businesses understand the market, identify what skills are in demand and what education is needed, and promptly provide training based on their understandings.

Artificial intelligence could be a useful tool for organizations to achieve this. Businesses, in fact, have already started adopting AI into their recruitment and employee evaluation processes. Likewise, artificial intelligence can be used to design education programs tailored to individual employees’ needs and career plans.

A case in point is KBC, a Belgian bank and insurance group. After encouraging all employees to participate in personalized learning programs, KBC developed a digital talent platform that provides information on recommended training programs that are aligned with the group’s growth strategy. In doing so, they created a “skills marketplace,” where essential skills for the company’s growth are “traded.” Moreover, they enabled workers to break the boundaries of traditional classroom education to take the reins and select their own training content. In addition, KBC implemented a “digital badge” program to certify workers’ acquisition of skills. These changes, in turn, increased productivity for the group and motivated employees to take advantage of the training programs.

Transparency can motivate staff and build support for retraining

For organizations to implement any training programs, it is imperative that they first build support for retraining among employees. To establish a shared understanding of the programs, employers will have to be transparent about the current circumstances and share their vision of what skills will become necessary in the future and what employees could expect from these programs.

In 2013, American telecommunications provider AT&T initiated massive retraining efforts after discovering that nearly half of its 250,000 employees lacked the skills to keep the company competitive. However, before they implemented the programs, AT&T actively engaged in discussions with its employees to communicate the importance of skills and provided program portfolios to facilitate the acquisition of new skills. Artificial intelligence played a role in this as well, providing employees with transparent, objective data of their skill sets and a better understanding of the market to allow individuals to take charge of their learning and choose courses that they need.

The IBM Institute for Business Value offers a roadmap for employers to address the skills gap and underscores the need for organizations to foster a culture of lifelong learning. “Gone are the days when any one company had all of the answers,” IBM says. “Gone, too, is the ability to solution the skills challenge without the partnerships of broader internal and external ecosystems.” To reduce the skills gap, IBM argues, companies must adopt innovative strategies and work with partners from internal and external ecosystems instead of limiting their efforts within their organizations.

Change is afoot for the world of work, and the paradigm of learning, or training, must change along with it.

[References]

1. Tae-Kyung Kim, Byung-Ho Lee. (2021) “The Impact of Industrial Automation on Employment”, [2021-1] Bank of Korea Periodicals, pp. 16-35.

2. Hyeon-Gon Kim. (2019). “Work and Education in an Era of Artificial Intelligence and Population Ageing”, Future 2030 Series vol1. Pp. 3. National Information Society Agency.

3. JoongAng Daily. “VR Office is almost here.”, 2021.1.31.

4. IMF. (2019) “Automation, Skills and the Future of Work: What do workers think?”, IMF Working Paper, December 2019.

5. LaPrade A. et al. (2019) “The enterprise guide to closing the skills gap”, IBM Institute for Business Value. September 2019. (accessed Feb.4.2021)

6. ManpowerGroup (2018) “2018 Talent Shortage Survey: Solving the Talent Shortage-Build, Buy, Borrow and Bridge”, ManpowerGroup. 2018

7. WEF. (2018). “The Future of the Jobs Report”, 2018.

- . (2019). “Towards a Reskilling Revolution: Industry-Led Action for the Future of Work”, January 2019.

- . (2020) “Closing the Skills Gap: Key Insights and Success Metrics”, November 2020.

This text was originally published on Yeosijae’s Korean homepage on February 9, 2021.

< Copyright holder © TAEJAE FUTURE CONSENSUS INSTITUTE, Not available for redistribution >