Please join Yeosijae as we build a brighter future for Korea. Create your account to participate various events organized by Yeosijae.

- Insights

- |

- Global Order and Cooperation

Facilitating an “Orderly Return to Normal”: Establishing a New Global Pandemic Response System

- Urgent action is needed to support vaccination programs in developing countries

- We need to establish an international fund to develop vaccines as global public goods

- South Korea and the US should spearhead the development of a new global pandemic response system

With vaccinations now underway,

The battle against COVID-19 is entering a new phase

The novel coronavirus that emerged in 2019 swept across the world at breakneck speed. The COVID-19 pandemic triggered unprecedented economic and social crises of a magnitude akin to war. Although more than 15 months have passed since the initial outbreak, no country has managed to escape its wrath.

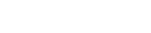

With vaccinations underway, the battle against COVID-19 is entering a new phase. Some countries now expect to reach herd immunity by the end of this year, assuming that vaccinations continue at their current pace.

(Source: Our World in Data, 2021. Accessed 22 March 2021.)

Some of the more successful countries are already preparing for a return to the world of free movement. Expecting to have vaccinations fully administered by mid-April, Israel is preparing to introduce a vaccine visa program that would certify COVID-19 immunity.

passport ‘Green Pass’

Countries left to ‘sink or swim’ on their own;

Our fragmented pandemic response will delay global recovery

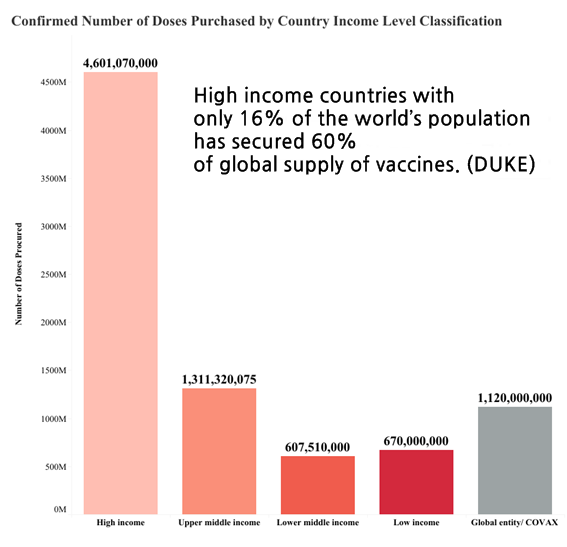

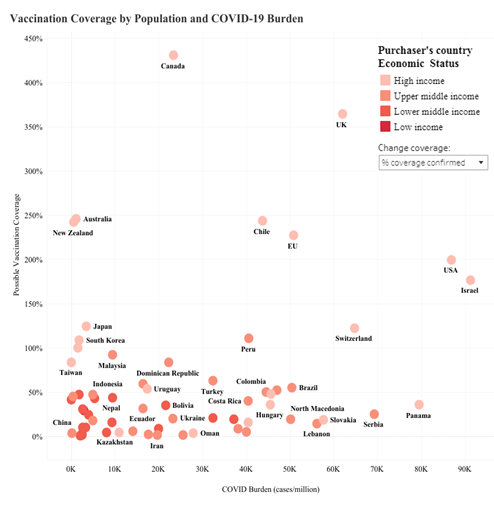

Are humans winning the war against COVID-19? Despite promising signs in a few successful countries, it is too early to be optimistic. There are drastic differences in the number of vaccines secured and administered across countries. Accordingly, it is highly unlikely that the existing gap in vaccine supplies will be filled in the near future. [Figure 3]

to secure COVID-19 vaccines

(Source: The Launch and Scale Speedometer, Duke Global Health Innovation Center

(last updated: 2021.03.08))

before 2023

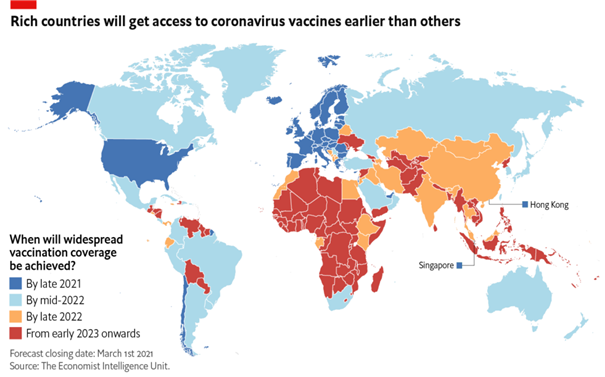

The Economist Intelligence Unit noted that more than 85 low income countries will experience vaccine delays and not have widespread vaccination coverage until 2023. [Figure 4] It is unfortunate that international efforts to tackle this issue are yet to be seen. International assistance and cooperation have been limited and fragmented up until now, as many countries are still engrossed with their own affairs. The plight of others, especially the developing world, is still beyond the concern of the international community.

‘Me first’ vaccine hoarding in wealthy countries;

Developed countries have secured more vaccines than they need

Vaccine nationalism is complicating the situation. In early March, the Italian government blocked the export of AstraZeneca vaccines to Australia. The EU had earlier introduced new regulations that block companies from shipping vaccines outside the region unless they have met their contractual commitments with the bloc.1) Italy was the first country to use this new rule. Reuters also reported on March 21 that the EU had rebuffed the UK’s calls to ship AstraZeneca COVID vaccines produced in a factory in the Netherlands, indicating that EU-made vaccines are for the EU.

(Source: France24, CNN) / EU rebuffs UK calls to ship COVID vaccines from Europe (Source: Reuters, AFP)

What is most alarming about this situation is the apparent imbalance in vaccine coverage between wealthy and low income countries. Some rich countries have already secured access to doses that could vaccinate their populations multiple times over, while middle-income and low- to middle-countries have not even obtained enough vaccines to immunize their entire populations. It should be noted, however, that this imbalance will only result in delaying our return to a world of free movement and trade.

(Source: The Launch and Scale Speedometer, Duke Global Health

Innovation Center (last updated: 2021.03.08))

International efforts are needed to facilitate

an “orderly return to normal”

What should be done to expedite an “orderly return to normal”? Many experts and administrators will discuss this question in depth. However, there are three key areas of focus for international cooperation. Collectively, we should:

(i) endeavor to ensure that vaccines are rolled out at roughly the same pace around the globe,

(ii) improve the efficiency of disease prevention and control measures as vaccines are rolled out; and,

(iii) identify ways to restore freedom of movement (address issues related to the issuance and certification of vaccine visas)

International efforts must address the financial need for vaccine procurement and public health infrastructure in developing countries.

The speed of vaccinations in a given country depends on its ability to secure (vaccine procurement capacity) and administer (healthcare system effectiveness) the shots. Access to vaccines comes from each country’s financial and diplomatic power. Furthermore, with vaccine nationalism more rampant than ever, the diplomatic capacity of nations has become just as important today as the ability to finance their purchases. Developing countries have neither the financial resources nor the diplomatic power to compete in the vaccine race.

Consequently, the international community needs to devise a policy framework to assist developing countries in procuring vaccines and upgrading their health infrastructure. Financing mechanisms should be devised to leverage multilateral financial institutions such as the World Bank, Asian Development Bank (ADB), and African Development Bank (AfDB), to bolster the financial capacity of developing countries to purchase vaccines.

International efforts are also required to ease the debt burden of developing countries. The World Bank reports that government debt among emerging markets and developing economies increased by nine percentage points of GDP in 2020, the largest surge since the late 1980s. Creditors should be encouraged to extend debt maturities, waive interest, or provide a debt standstill at least until the pandemic is over.

Healthcare infrastructure is another critical component in the deployment of vaccines. Vaccine distribution in developing countries will be challenging given the state of healthcare infrastructure. The international community needs to come up with measures to upgrade health infrastructure in developing countries to address the infrastructure gap and reduce the disparities in vaccination rates. In particular, it is important to improve the infrastructure that ensures safe storage, distribution, and administration of vaccines.

COVID mutations could limit the effectiveness of vaccines;

We must continue to curb the spread of COVID-19 as we move through the vaccination process

Continued efforts to contain the spread of COVID-19 infections is no less important in the vaccination process. There are currently encouraging signs, with COVID cases falling in countries that have been swift to roll out vaccine programs. The UK, one of the first countries to start COVID-19 vaccinations, recorded a drop in the number of new cases after 41 days of vaccinations, and the figure for the US was 28 days.2) The rate of infections tends to fall about a month into vaccinations. Israel, in particular, showed a 92% drop in severe cases of COVID-19 infections.3)

(7-day moving average)

(Source: Johns Hopkins University, as cited in an article from Dailypharm, 2021.02.05)

Not every country is following the UK’s trajectory, however. Despite ongoing vaccinations, we are yet to see a significant drop in the number of new global COVID cases. Moreover, the emergence of COVID variants has complicated the situation even further. Signs of a third wave of infections are emerging in countries lagging behind in vaccine rollouts, and this is largely due to the spread of variants. In France, the UK variant accounted for more than three-quarters of recent COVID infections.4) Italy, Germany, and Poland have also tightened coronavirus restrictions, recognizing that a third wave of COVID-19 is sweeping across the region.5)

Keeping COVID cases under control as vaccines are rolled out is essential to achieve the goals of vaccination. Vaccinations must outpace new infections. It is unclear whether the vaccines that we have now provide immunity against all variants. If infection rates outpace immunization due to delays in the process, it could raise the chance of more variants emerging and jeopardize the effectiveness of available vaccines.

For vaccine visas to work, we need to cooperate and

Establish globally recognized standards

The third question at hand is how to ease international travel restrictions. Some countries have decided to introduce vaccine visas. However, restoring free cross-border movement is not simply a matter for each government to decide on its own. Several challenges must first be addressed for vaccine visas to be implemented:

(i) mutual recognition of vaccines,

(ii) the credibility of vaccine visas, and

(iii) issuance and verification of vaccine visas

Recognition of vaccines pertains to the question of which vaccines are accepted into the program. As of today, March 22, a number of vaccines are available worldwide, mostly in developed countries. The US has approved three vaccines; Johnson & Johnson, Moderna, and Pfizer, while the UK has approved AstraZeneca and Pfizer. Israel, on the other hand, has approved Moderna and Pfizer, while Russia has approved EpiVacCorona and Sputnik V, and China has approved Sinopharm and Sinovac. The problem is that governments have authorized different vaccines due to uncertainty and differences in vaccine efficacy.

Reaching a consensus on vaccines may seem like an easy task, considering that vaccine development and production are limited to a small number of countries. However, this may not be the case in reality. International politics may complicate mutual recognition of vaccines. Already, there are some doubts about vaccines developed by certain countries. If this is the case, the world could become divided into ‘vaccine blocs’ in the future.

Ensuring the credibility of vaccine visas is another problem. With the widespread use of smart technologies, vaccine visas are likely to be app-based certificates. However, due to the differences in the level of IT security technology, vaccine certificates will come with various security risks that could undermine their credibility. The credibility of certificates could set countries apart, similarly dividing the world into ‘vaccine blocs.’

International coordination and cooperation are critical to ensure the effectiveness of programs, whether it be the distribution of vaccines or vaccine visas. A well-coordinated framework for international cooperation and oversight should be put in place to facilitate an orderly return to normal.

Infectious disease epidemics are occurring more frequently;

There is a pressing need for a permanent global response system

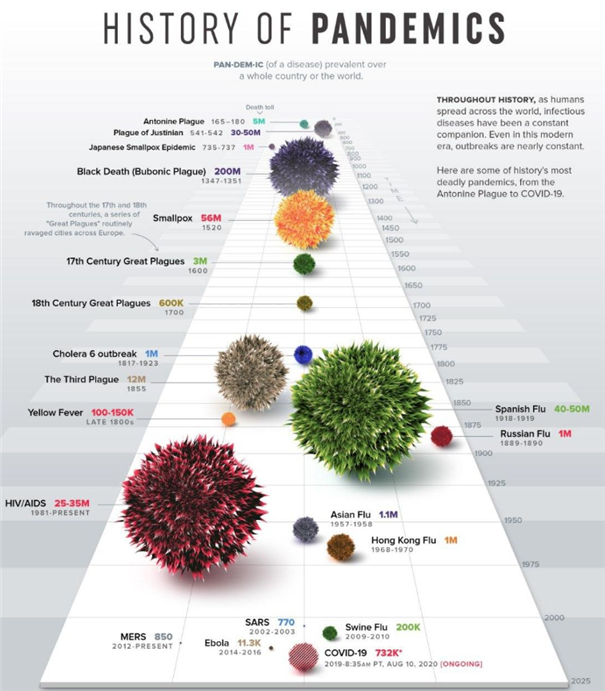

While we should prioritize efforts to establish a framework for international cooperation to facilitate an orderly return to normal, it is also imperative that we take steps to improve the global response framework for preventing future pandemics. Many experts point out that COVID-19 may not be the last pandemic. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), epidemics of infectious diseases have occurred more frequently since the turn of the millennium. Epidemics have increased significantly over the past decades, from 991 cases in the 1980s to 1,924 in the 90s, and 3,420 in the 2000s. This trend appears set to continue in the future, which means the interval between pandemics will become shorter and shorter. The next pandemic may be right around the corner. Considering that the current pandemic has already demonstrated a vicious capability to mutate multiple times over a relatively short period, we cannot simply overlook these concerns.

(Source: Visual Capitalist (2020.3.14))

With the devastation that COVID-19 has caused around the globe,

We have every reason to invest in and pursue international cooperation on pandemic prevention

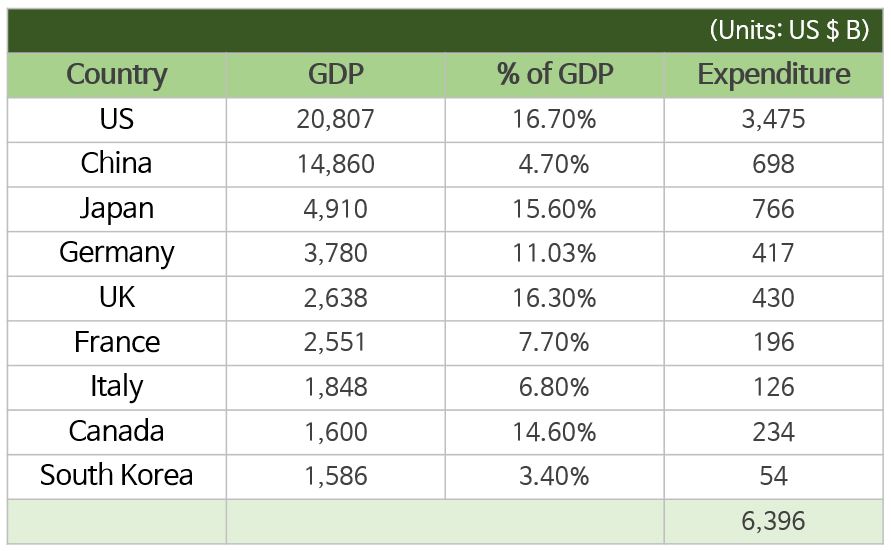

The economic and human costs of a global pandemic are far too great to pass it off as something that will pass with time. Take, for example, the economic costs. According to the World Bank, the global economy contracted by 4.3% in 2020, recording the biggest plunge since the end of World War II (a contraction of 9.8% was recorded in 1945). It is estimated that the COVID-19 pandemic has cost the global economy US$3.8 trillion. The aggregate cost of fiscal support in just nine countries, which has been extended to mitigate the economic impact of the pandemic, amounts to US$6.4 trillion. All in all, the pandemic has cost more than US$10.2 trillion.

The world needs a global response mechanism that has the power to enforce compliance,

Not one that relies on certain countries to take action

The current global pandemic response system needs to be improved in two ways. First, a new system needs to be put in place to enforce measures for early detection and prompt containment of infectious disease outbreaks that have the potential to become global pandemics. One big lesson from the coronavirus pandemic is that it is too risky to rely solely on the goodwill of countries to detect and control outbreaks in their early stages.

The new system must address moral hazards in future pandemics. It should be supported by an organization with the capacity to enforce its decisions. An international agreement involving all countries should be made to establish this system. We need to consider signing a Global Anti-Pandemic Action Agreement, or GAPA for short, and discuss how to create an international organization with enforceable powers that would enable continuous monitoring, early detection, and swift action under the agreement.

The international community needs to engage in multilateral efforts to support vaccine development

Second, the new system should be designed to promote global collaboration on vaccine development. As epidemics appear to be more frequent and have higher mutation rates, developing universal vaccines that are effective against all strains of viruses is the best option. As it so happens, the UK company Scancell and the University of Nottingham have announced plans to develop ‘variant-proof’ COVID-19 vaccines.6) UK biotech company ConserV Bioscience is also developing an mRNA-based universal COVID vaccine that it hopes to take to clinical trials by the end of the year. Similiarly, the American company VBI Vaccine is planning to conduct clinical trials sometime this year on its pan-coronavirus vaccine, which is designed to be effective against SARS, MERS, and COVID-19.7) If universal vaccines are technologically possible, then we must consider measures to develop, produce, and distribute them as global public goods.

Another thing to note is that the vaccine industry faces a unique type of market failure. Because pandemics occur infrequently, companies have little incentive to invest in vaccine development in normal times. This is why we rarely come across companies that spend trillions of dollars developing vaccines for which there is no pressing need.

The world needs an international vaccine development fund

How much are we willing to pay to prevent a global crisis? While vaccine experts may provide a better estimate of the cost of global vaccine research, we can answer this question by evaluating the risks involved. First, consider the aforementioned economic costs of the pandemic. In the most conservative estimates, COVID-19 is expected to cost almost $10 trillion (both directly and indirectly). This equates to around 11% of the world’s GDP, which was $87 trillion as of 2019. Accordingly, it should not be a waste to spend $1 trillion (or 10% of the damage) to prevent another pandemic of this scale.

Another benchmark is global military spending. The top 10 countries with the highest military expenditure in the world spend almost $1.3 trillion annually on defense. If that is the case, then why not spend $100 million (or roughly 10% of military expenditure) on vaccine development? Pandemics have emerged as one of the biggest non-traditional security challenges8) in today’s world. They pose a threat beyond the scope of traditional security that could cause serious disruption to human activities. Considering that pandemics are just as destructive as war, we should be able to reserve the same amount of money, or even $100 million, to prevent them from occurring.

(Source: Munhwa Ilbo. (2021.02.26))

Suppose that we come to an agreement to establish an organization to enforce the terms of that agreement. In that case, it would be necessary to establish an international fund for vaccine development (or GAPA Fund for Vaccines) with contributions mostly from wealthy countries around the world.

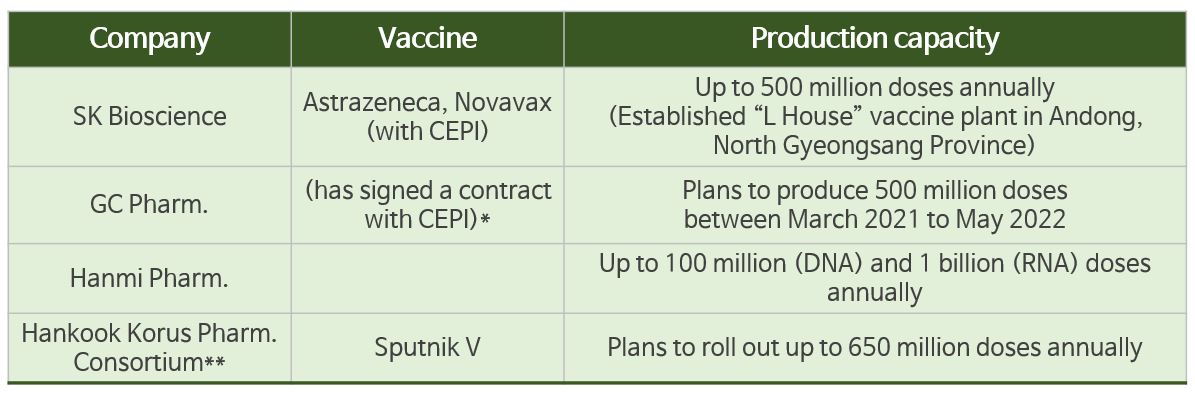

South Korea and US may play a leading role to improve the current system

Who will lead the discussions to improve the current system? The prime candidates will be those countries best equipped to set up the framework for vaccine development, distribution, and vaccination. As one of the leading biotech nations in the world, the US was among the first to develop and distribute a coronavirus vaccine. South Korea is another of the countries that has the capacity to mass-produce vaccines, alongside India, China, the UK, and Germany. South Korea is estimated to have the ability to produce more than three billion doses, given the current production capacity in place.

*CEPI contract: a CMO contract with the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) to produce COVID-19 vaccines.

The vaccines that GC Pharm. will produce are undetermined, but GC Pharm. plans to produce 500 million doses by May 2022.

**Hankook Korus Pharm. Consortium: a consortium that consists of Andong Animal Cell Culture Substantiation Center, Binex,

Boryung Biopharma, ISU ABXIS, Chong Kun Dang Bio, Quratis, and Humedix

Furthermore, South Korea is capable of producing all four types of vaccines in Phase III trials (viral vector, inactivated, nucleic acid (RNA, DNA), and protein-based vaccines).9) According to Dr. Jerome Kim, the Director-General of the International Vaccine Institute, another one of South Korea’s strong points is the ability to produce quality products at a low cost.10) South Korean pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies have been adopting smart factories even before the pandemic. Most importantly, South Korea has accumulated valuable experience and expertise in effectively containing pandemics, which could be utilized to develop a new response system against potential pandemics. From this perspective, South Korea and the US could be the right candidates to lead these discussions. Experts from South Korea and the US could work together in spearheading efforts to facilitate global cooperation for speeding up the orderly return to normal, and building a new international system to facilitate a coordinated response to future pandemics. The upcoming G7 and D10 meetings should serve as suitable occasions to begin discussing these matters.

1) https://www.bbc.com/korean/international-56290246

2) According to data from Johns Hopkins University cited in an article by Dailypharm, the number of confirmed cases in the UK peaked on January 9 and has since plummeted. The average number of confirmed cases in the US also increased from 646.2 per million at the start of vaccinations on December 15 to 753.3 cases on January 11, but has consistently declined ever since, falling to 413.9 cases on February 3. Canada, which rolled out its vaccine programs on the same date, saw an increase from 175.3 cases per million people on December 15 to 255.1 cases on January 9, but has also seen this figure subsequently drop, with 108.0 confirmed cases on February 3. (Dailypharm. 2021.02.05. http://www.dailypharm.com/Users/News/NewsView.html?ID=273251 )

3) BBC News Korea. 2021.2.2.

4) https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20210319006100081

5) https://www.segye.com/newsView/20210315514873

6) https://www.ytn.co.kr/_ln/0104_202102150726368586

7) https://www.chosun.com/economy/science/2021/02/25/QE2F5INPQRFAJLQCZ74OECZI4U/

8) Non-traditional security: Non-traditional security focuses on new security challenges that are typically non-military in nature, such as pandemics, natural disasters, and cybersecurity. Shin-Wha Lee characterized non-traditional security threats as (1) non-military, (2) transnational risks that (3) concern not only the well-being of states, but also other stakeholders. [Lee, Shin-Wha. Non-traditional Security and Regional Cooperation in Northeast Asia, Korean Political Science Review, 42(2).]

9) https://www.greenpostkorea.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=124266

10) https://www.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2020/08/20/2020082000295.html

< Copyright holder © TAEJAE FUTURE CONSENSUS INSTITUTE, Not available for redistribution >