Please join Yeosijae as we build a brighter future for Korea. Create your account to participate various events organized by Yeosijae.

- Insights

- |

- Future City/Future Housing

[Post-COVID-19 Era / Cities ②] Rediscovering “Local”

Is “Local” an Alternative?

Since our inception, the Future Consensus Institute (Yeosijae) has focused on “the urban civilization crisis” to study different trends, backgrounds, and possible solutions to the crisis. Discussions in the past were primarily focused on the sustainability crisis of large cities and the loss of small towns. With the outbreak of COVID-19 taking issue to the global center stage, we would like to share our findings in four parts.

- Metropolis in Crisis

- Rediscovering “Local”

- On the Grounds of “Local”

- The Future of Cities: Decentralization

District Office Homepages and Online Mom Groups

The COVID-19 crisis has shifted our attention back to our homes, daily lives, streets, and neighborhoods. Out of those changes, the most significant change for the Korean society was the “rediscovery of local neighborhoods”, stemming from our efforts to control the coronavirus. People turned to district office homepages and online mom groups, as they sought out information on their respective neighborhoods. Emergency alert messages sent by local administrations, instead of the central government, highlighted the importance of conducting containment measures on local levels.

Spending More

And Traveling Around Home

Social distancing has significantly changed our world. Restrictions on movement and large gatherings have confined people to their neighborhoods, bringing local stores, streets, and businesses back into the spotlight. In fact, off-line consumption decreased overall, while “Home-Around” spending (or the money spent around home) increased when COVID-19 was running rampant in April. A growing number of tourists are choosing to stay closer to their accommodations to enjoy the local culture, instead of venturing out to different areas.

Then will “local” become an essential part of our life? Before COVID-19, the word “local” had two meanings in Korea. One which referred to “local” favorites, used by tourists to look for restaurant recommendations.

The other meant “alternative space”, referring to the stores in the alleys and streets of our neighborhoods, where local business owners and consumers meet. For these people, the word “local” would signify an independent alternative space that is free from the existing cultural norms. With COVID-19, “local” neighborhoods have started to hold new significance in the spheres of our life.

An Item on the Post-COVID-19 Agenda:

Job Creation

Restructuring our cities around our sphere of life in the Post-COVID-19 era will require us to address the economics of a “neighborhood” economy. Local neighborhoods will have to offer a sufficient number of jobs for their residents for them to hold significance in our life sphere. Policies for a “neighborhood” economy should also differ from those of an industrial society. Different regions, in an industrial society, had to compete against each other to attract national industries to their area. However, COVID-19 demands that we create a virtuous cycle of growth that boosts local industries and economies, thus leading to a shift to a “neighborhood” economy. While national industries will continue to exist in the post-COVID-19 era, local industries will exert greater influence on our economy compared to the past.

In fact, this is not the first occasion that the concept of a “neighborhood or compact” city has been raised. Industrial cities suffering from population decline have often concentrated commercial and residential facilities in downtown areas to leverage resident-friendly city projects to improve the urban environment and the welfare for the elderly. Global metropolises have breathed vitality into local areas to improve the quality of life for their residents. Paris is a case in point, with its recent announcement of a 15-minute city plan that will reshape the city to allow residents access to essential infrastructures within 15 minutes from home. In this context, how should South Korea build its “neighborhood” cities in the post-COVID-19 era?

City A versus B

A Tale of Two Cities

One hint to the answer can be found in the tale of two cities that began in South Korea in the 2000s. The tale speaks of two models of cities: “modern” and “post-modern”. The former portrays a typical city that is ‘office-, corporate-, and automobile-centric’, where city planning focuses on ‘redevelopment’. Its rival, in contrast, is a ‘resident- and pedestrian-friendly’ city that focuses on ‘urban regeneration’. Whichever model that enables a more systematic and effective city planning will come out on top as the winner and decide the future of South Korean cities.

Fundamentally, the lifestyles of residents will determine the winner. Currently, South Korea is divided into two halves, one that prefers newly built cities and the other that favors existing cities. This would mean that the former would be in line with “modern model”, whereas the latter would be closer to the “post-modern model”. The Korean government has actively promoted urban regeneration since 2010, which has created a conflict between the two sides. Reconstruction project unions, representing the modern side, are colliding with their counterparts in the post-modern side, composed of building owners and owners of small businesses. The main issue, however, comes from the government’s lack of communication with its residents in determining the preferred model for their city. Doing so has led cities to apply both models at the same time in the same area, creating unnecessary chaos as a result.

For the sake of convenience, modern cities will hereinafter be referred to as ‘City A’ (or Type A) and post-modern cities as ‘City B’ (or Type B). In simple terms, Type A cities are home to tall buildings and large corporations, whereas Type B cities are lined up with relatively shorter buildings and smaller businesses. To put this into context, the cities of Yeouido and Gangnam resemble Type A cities, while Hongdae and Itaewon draw closer to Type B. In terms of urban planning, City A would be associated with urban redevelopment, and City B with urban regeneration. In this context, implementing a city regeneration project would signal a shift towards City B.

The defining characteristics of City A would include an emphasis on advanced urban infrastructure and a business-centric environment that hosts many large buildings, business complexes, and corporations. Type A cities are likely to develop into smart cities or IDEA (Innovation, Design, Entrepreneurship, and Arts) cities. On the other hand, City B would be a cluster of villages, with many walkable streets and more small, old buildings compared to the number of new buildings. Creators and creative thinkers that work in our small stores and SMEs gather in such places. To sum up, Type B cities are essentially “lifestyle cities” as they emphasize lifestyles and are similar to what Richard Florida described as “creative cities”.

Cf. Richard Florida

An economist, trend analyst, writer, and speaker, who coined the term “creative city”.

He is a senior editor at the Atlantic and the co-founder of Citylab. His books, including “Who’s Your City”, have served as a guidepost for the global discourse among scholars.

The Millennials Prefer City B over City A

With new towns springing up like mushrooms throughout South Korea, City A may appear to be the direction the country is headed for. However, recent trends prove otherwise, with the Millennials especially preferring Type B cities over Type A, as these cities are more local-oriented and resident-friendly.

These characteristics of Type B cities have taken various forms in real life, with the most prominent change occurring in the local businesses. Local businesses (or ‘neighborhood businesses’) emerged after the 2000s and has since dominated the off-line market. When the Millennials swarmed the streets of Gangbuk, even the media began to ask questions about why the Millennials “are heading to our streets and alleys”.

Changing Lifestyles:

From Status and Competition to Character and Diversity

The shift towards local neighborhoods is only a part of a bigger trend in our lifestyles. People are moving from materialistic lifestyles that emphasize status, survival, competition, and diligence to post-materialistic lifestyles, that are more concerned about individual character, diversity, quality of life, and social responsibility. Post-materialists are more likely to prefer Type B cities, considering that these cities incorporate history, culture, and urban life.

The local orientation of the Millennials has also garnered attention. As Keiko Matsunaga points out in , the Millennials build their lifestyle around their neighborhoods. This becomes evident in their search for neighborhoods with a Starbucks within walking distance, a ‘hot place’ or a hot spot bustling with people, and places to shop in close distance.

Cf. Keiko Matsunaga

A professor at Osaka University, known for her published work titled ‘Local-oriented Era’ (2017). Her work captured the growing influence of “local” strategies, drawn from her research of small- and medium-sized cities throughout Japan and the world. Her expertise lies in the field of regional industries.

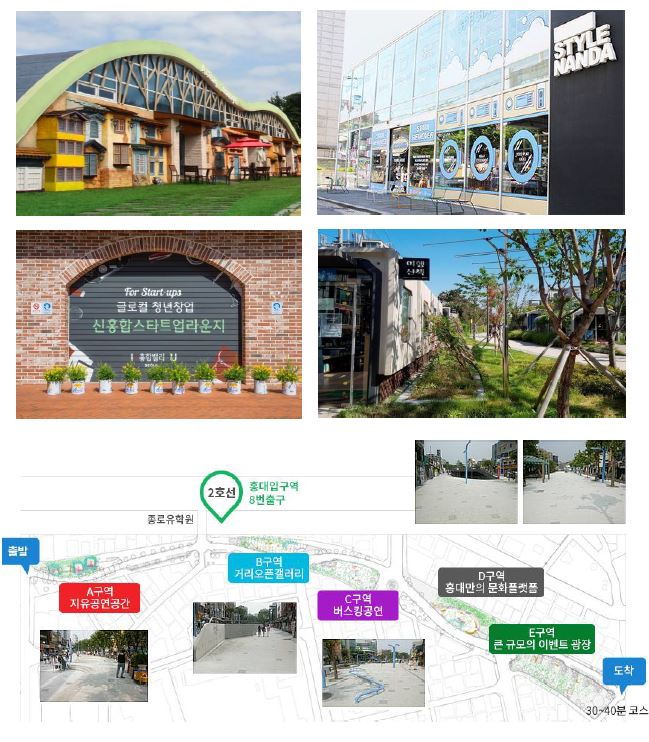

in Hongdae. (Source: Jong-Ryn Mo)

Local Business:

The New Growth Engine

The importance of local commercial districts has been widely recognized, and has prompted giants in logistics and construction to make their way into the neighborhoods. The question now is, how should small business owners cope with the introduction of large businesses and how should the government assist them?

Looking at the four trends—the rise of local businesses, the change in lifestyles, the emphasis on “local”, and the participation of large corporations— future urban planning is likely to favor the Type B model. Even in the terms of the economy, where Type A cities are considered to have the upper hand, Type B cities could create more opportunities, considering that local businesses will become the foundation of future industries. After all, cultural and creative industries—the engines of our future—are more likely to flourish in downtown areas. For that reason, accelerating the growth of future industries will require more cities to adopt the Type B model.

Change is already occurring in our alleys, with streets filling up with cultural and creative industry businesses. Galleries, photo studios, workshops, select shops, architecture and design studios, and other small businesses with high cultural value are growing into creative businesses like co-working spaces, multicultural complexes, social ventures, entertainment agencies, and urban regeneration startups. These alleys with local, cultural, and creative industries could become the new growth engine for South Korea.

Hongdae is an example of a city with an urban business ecosystem and a similar environment is emerging in Seongsu-dong as well. In the past, creative, cultural, and local industries were dealt with separately. However, the three industries will now have to come together, with local industries at the center. Talent will be the most important resource to support the growth of local businesses. On this note, I would like to refer to my proposals made in the to suggest that universities and training institutes for artisans are established to nurture more talent.

Danggeun Market’s Secondhand Service and

Gunsan’s Local Food Delivery Service;

Urban Amenities Attract Talent

Cities of different sizes will need to take on different approaches when it comes to applying the Type B model. A large metropolis will need to connect several B cities together, while small- and medium-sized cities would need to concentrate their resources in a downtown region. In other words, one will require a decentralized version of the B model, while the other would need a centralized version.

Building a successful Type B city will require an integration of walkability in its design. This does not simply mean building better sidewalks, but designing a city full of entertainment, character, and culture. Developing such cities will eventually create compact cities, where work, life, and leisure facilities are placed close to one another.

Likewise, integrating technology in Type B cities will also be important. Technologies of the 4th Industrial Revolution, including green tech, pedestrian-related technologies, regional innovation technologies, and technologies in small and medium-sized enterprises, are necessary components of Type B cities. Local creators, who have driven the growth of local businesses in Type B cities, are already actively leveraging digital social platforms (including the social media, online shopping malls, and crowdfunding services). Naver’s location-based services and “our neighborhood” service, Danggeun Market’s local secondhand trading service, and Gunsan’s local delivery service are some of the examples of location-based services and technologies that are needed to bring “neighborhood” cities to life.

Amid the global changes in lifestyles, South Korea will need to take charge and pave a way forward. “Neighborhood” cities were the megatrend of our age even before the spread of COVID-19, and the pandemic has only served to accelerate this on-going trend. Now, South Korea will have to rise to the challenge of attracting both domestic and foreign talent to their cities to lead the post-COVID-19 era.

This text was originally published on Yeosijae’s Korean homepage on May 28th, 2020.

< Copyright holder © TAEJAE FUTURE CONSENSUS INSTITUTE, Not available for redistribution >