Please join Yeosijae as we build a brighter future for Korea. Create your account to participate various events organized by Yeosijae.

- Insights

- |

- Future City/Future Housing

- Next-Generation Values

[Post-COVID-19 / Cities ③] “Localizing Business” On the grounds of “local”

CCEI Gangwon Director Jong-Ho Han discuss what cities mean for the Millennials.

Since our inception, the Future Consensus Institute (Yeosijae) has focused on “the crisis of urban civilization” by studying different trends, backgrounds, and possible solutions to the crisis. However, the COVID-19 outbreak has presented a new landscape with a new set of challenges. Taking this into account, we would like to share our findings in four parts. As the third text of the four-part series, we invited the Director of the Gangwon Creative Economy and Innovation Center, Jong-Ho Han, to Yeosijae to share his insights. His presentation has been summarized below.

1. Metropolis in Crisis

2. Rediscovering “Local”

3. On the Grounds of “Local”

4. The Future of Cities: Decentralization

PRESENTATION FROM JONG-HO HAN (CCEI GANGWON DIRECTOR)

I was yet to form any goals or missions for the organization when I started working as the director for the Gangwon Center for Creative Economy and Innovation six years ago. However, over the years in my work, I came to see the potential in “local rebranding” as an industrial strategy. I would like to take this opportunity today to share my experiences at the CCEI Gangwon so that you can understand how I arrived at that conclusion.

The Center for Creative Economy and Innovation

Established during the Park Geun-Hye administration, the Creative Economy and Innovation center was put in a precarious position (for obvious reasons) when President Moon Jae-In took office. However, Prime Minister Lee Nak-Yeon, perhaps due to his previous experience as the Governor of South Jeolla Province, defended the CCEI before a hearing by emphasizing its role in the local community. At the time, the South Jeolla Province CCEI worked with one of the few South Korean conglomerates with a healthy corporate culture, the GS Group, to make some remarkable achievements in the region that otherwise would have been difficult for government agencies to emulate. President Moon also backed CCEI when he referred to the center while mentioning that “the new government should keep things that are working, even if they are initiatives started by the previous administration.” Our position and reputation in South Korea have only grown since then. Though we were once a “startup incubator” during the Park administration, we are now focusing more on local businesses with efforts accompanied by investment projects. Though the slogan of the “Creative Industry” is long gone from government agendas, the Center for Creative Economy and Innovation still stands firm.

It is, in fact, worth noting that the “Creative Economy” was not developed by the Park administration. Instead, it was introduced by the Blair government in the late 90s, when people, facing capitalism’s tendency for the rate of profit to fall, began to argue that creative technologies should be considered a factor of production, similar to land, capital or labor. The Creative Industry gained traction again in 2004, when it was introduced in the economic and development agenda for Least Developed Countries by the United Nations, which in turn, influenced the Roh Moo-Hyun administration to push for “Innovation Cities.”

Starting from the Bottom of the Ladder

Getting ready to take up my position in 2015, I looked up Gangwon Province in search engines to see what would appear. The results, with some exaggerations, were mostly tourist spots and local cuisines. The Gangwon province accounts for a sixth of the landmass of South Korea, roughly about 18 times the size of the Jeju Island. However, 82% of its land is covered by forests, while the population is just over 1.56 million people. Gangwon also lags behind in startup indexes. Only one of the 300 South Korean venture capital investors and just two of the 300 businesses in the angel club list by the Ministry of SMEs and Startups are located in the province. This sadly leaves the honor of raising a toast in the New Year’s party with local economic leaders to the Director of Korea Federation of SMEs (KBIZ).

Changing the Paradigm

Yet when I finally arrived in Chuncheon, I discovered that a number of people were already making a living on localized business models. More appeared in 2015, when Professor Jong-Ryn Mo fueled a boom in local models by introducing the concepts of lifestyle-oriented cities and alleyway economics. And with COVID-19, I believe the world is once again reflecting on the shortfalls of its corporate-oriented cities.

In 2017, the New York Times selected Jeonpo Café Street as one of the “52 places to go”. Upon hearing the news, I asked one of my friends who lives in the region about the street. However, he replied that he thought it was a street with hardware stores, and had no knowledge that it had become a tourist spot. Even so, for the New York Times, it was a stretch of road worth highlighting. This example, I believe, goes to show that people are gradually moving away from traditional tourist spots to those with content that caters to the Millennial’s tastes.

The Rise of Local in Japan

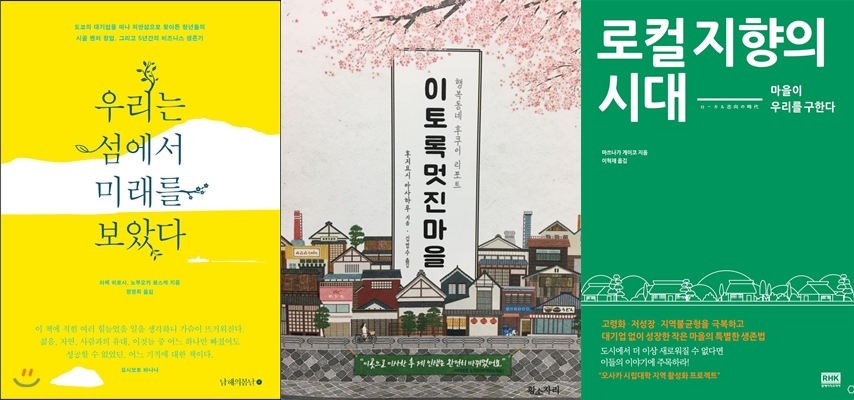

I want to highlight Japan for a moment. When the nation was devastated by the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, people began to look inwards, to their neighborhoods and streets. And they began to question the central government, asking what it has done to help them overcome the aftermath of the disaster. The local-oriented sentiment grew in 2014 when the Masuda Report warned that half of the cities in Japan are in danger of going extinct. This prompted the locals to take matters into their own hands, and I would like to briefly introduce three books that recount Japan’s experience of ‘going local’.

1. “We Saw the Future in Islands” (僕たちは島で, 未來を見ることにした)

This book tells a story of two young men, named Abe and Nobuoka, and their struggles to survive in the remote island of Ama. The two authors—one a former engineer of Toyota Motors and the other a web designer—describe their efforts to build an “island school” in the small island. The school they had built is now an essential part of training for new civil servants and large corporation employees. They say, “What we need on the island are people of action, not critics.” Through their book, the two authors provide a hint to a future that will eventually come to pass in metropolises like Tokyo.

2. “Fukui Model: The Future Begins in ‘Local’” (福井モデル 未來は地方から始まる)

Written by the former journalist for the weekly Shukan Bunshun and the current Deputy Editor of Forbes Japan, Masaharu Fujiyoshi, this book describes what made the Fukui prefecture the “best region to live in Japan” for the last ten years. The Fukui prefecture, a small prefecture with a population of 790,000, outshines even Tokyo in terms of income levels and students’ mathematical scores (by almost 10 points). In short, the author explains this phenomenon by concluding that “regions that experience a crisis first get a head start on development, which in turn creates opportunities.”

3. “A Glimpse of the Trends, Industry, and Economy of the Local-oriented Era” (ロ-カル志向の時代 動き方, 産業, 經濟を考えるヒント)

Through this text, Keiko Matsunaga and the Osaka University offer insights on local vitalization projects throughout Japan and the world. Examples highlighted in the book convey the message that local regions, instead of extinction, have a promising future ahead of them. It also urges stakeholders to take immediate action to harness the potential of local regions.

Taste Consumption

Gangwon was the last region in South Korea to enter the Industrial age. However, changing paradigms from the advent of industrialization brought new opportunities for Gangwon and ‘local’. One may ask, why do people flock to Seongsu-dong and Iksun-dong? Several answers, including the post-materialistic individualism amongst the Millennials and their lifestyles based on personal taste, could be presented. But in short, it is because people are choosing to be self-expressive. The Millennials decide how they consume products and services based on their own taste, and as a result, crowds gather in places that reflect this growing trend.

Then why do local governments shy away from making investments in these areas? Unfortunately, structural issues prevent public servants from investing in areas that require time to show results. Public officials are evaluated on an annual basis, implying that they will have to show results by the end of the year. If they fail to do so, they will find it difficult to secure a budget for the following year. This is why public organizations are inclined to make ‘hardware’ investments instead of software investments, and explains why some investment keywords, such as the Fourth Industrial Revolution, are prioritized while investments for local branding are on the back burner.

Investing in ‘Local’

This is why we are pushing for more investment in local, to support those who can create value and cater to the Millennials. Some might say that this is a ridiculous idea, but we have committed ourselves to this path.

Currently, we are working with about 160 local creators to create creative spaces and products that reflect local values. When people say that Portland is one of the best places to live in the US, it is because the city is brimming with character. To emulate Portland, we pair our creators with designers and other experts to help them develop their business.

Some of our investments are already yielding results.

1. One couple utilized their experiences as a CJ E&M PD and a guitarist to take an inn at the edge of a red-light district to remodel it into a unique guesthouse. Now, the inn is famous for its beach yoga/meditation program that visitors can enjoy during their stay.

2. More than 500,000 people visit the Chilsung Shipyard in Sokcho every year. Though the word “shipyard” may evoke an image of a large dock like the Hyundai Shipyard, the Chilsung Shipyard is closer to a humble garage for boat maintenance. The shipyard originally went out of business a few years ago, but a group of young people transformed the space into a café, turning it into one of the best photo spots in Korea. Over 3,000 people visit the shipyard daily on weekends, and it has been selected as one of the ten best tourist attractions by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism.

3. In Yangyang county, there is a surfing shop that attracted over 700,000 visitors in just six months between July and December of last year. What makes this shop unique is that it is located in a security area, controlled by the nearby military base and surrounded by barbed wire fences. Instead of removing the fences from the area, the owner of the shop received permission from the military to allow civilians to enter the zone to surf. Korea is the only divided state amongst the OECD countries, and keeping the fences has allowed the shop to retain customers by offering a chance to surf in a unique setting.

4. One bakery in Pyeongchang became famous for its exquisite bread, made with locally produced ingredients including buckwheat, eggs, milk, and butter.

There are many other examples of successful local businesses. Though the craft culture is thought to have died out when the age of industrialization dawned, these young people are breathing life back into it by promoting value-based consumption.

Colors and Patterns of Gangwon

The Gangwon Center for Creative Economy and Innovation promotes the growth of local businesses in various ways. For example, we are accelerating the development of promising businesses by pairing them with investors. Impact investors have recently joined us in our efforts, including Sopoong Ventures, an impact fund created by the founder of Daum, Jae-Woong Lee, which has established an office within CCEI Gangwon to seek out potential business partners.

In our work, we often see young business owners submit poor business plans, which is only to be expected, seeing that most of them are opening a business for the first time. That is why we partner them with various experts to help them reflect on their business plans. We also bring in writers and designers to consult and promote their business. Other projects that we have been working on include: creating a unique palette of Gangwon to make calendars and books, designing patterns, and launching a brand called Gangwon Migam (Gangwon Aesthetics).

During the Park administration, the CCEI was given an impossible mission—to discover businesses like the AlphaGo. Because of this, rebranding projects sometimes had to be kept under wraps. But a change occurred earlier this year, when the Ministry of SMEs and Startups allocated 4.4 billion won to support 140 local creators. And to my knowledge, the government is planning on investing an additional 9 billion won in the second half of this year, with more to come next year. Rebranding businesses to reflect the values of local regions will become critical for local economies, and as a result, local administrations will have to continue to build an ecosystem to support this strategy.

[Remaining Challenges]

1. I believe that the dominance of cost-efficiency culture is limiting the expansion of value-based consumption.

2. South Koreans are accustomed to a top-down approach that was introduced by the Park Chung-Hee administration and reinforced under different names over the years since the Kim Young-Sam administration’s efforts to promote “local-specialized industries.” Local administrations are bound to the top-down approach because they lack fiscal autonomy, and this has pushed local-oriented models out of the spotlight. Japan was able to make reforms, after the publication of the Masuda Report, by implementing the Measures for Towns, People, and Job Creation, allowing the government to allocate budgets for long term projects (i.e. 4-5 years). I have high hopes that South Korea will be able to make the same changes.

3. Local administrations lack measures to alleviate the ‘last mile’ problem. A large part of the national budget is used in local regions every year, and I hope that more of this money would be used to invest in software, technologies, and designs.

[Suggestions]

1. The budget support system should also cover mid- to long-term projects.

As Japan did with its Measures for Towns, People, and Job Creation, South Korea should implement a support system that takes the focus out of short-term, results-oriented projects to give priority to long-term projects that will develop local values. It will have to leverage management systems that are tailored to each region and provide a sufficient amount of time for businesses to take root.

2. Local governments should promote and encourage private assistance groups.

The “last mile” is a telecommunication industry jargon that refers to the last leg of communication networks that deliver services to customers. Currently, our administration system lacks the ability to close the last-mile gap. Like the public sector, private partners in public projects are also confined to short-term projects that seek to produce immediate results. Local governments should strive to promote private assistance groups to provide intermediate-stage support and solve the last mile problem.

3. Local government should expand software-oriented support for creators.

The software aspect of business has more important than ever. In today’s world, the design of a product could make or break a business. Creating quality products, services, and content requires the combination of technology and design, which is why we have to make long-term, software-oriented investments to create local brands and values, and seek out creators who can commercialize them. Then creators, as entrepreneurs, will build their communities and ecosystems to create new opportunities and a better city.

[The Future]

Seeing the Future in Rural Regions

My hope is that, instead of a top-down approach that relies on a higher authority figure, local people would encourage small projects that will nudge their towns closer to their ideal cities. Doing so will create some interesting changes in our towns, and ultimately, foster creators, grow small businesses, and form communities and markets around our interests. Small online groups will expand to become large communities with over one million participants. The BTS fandom, for example, was a small network of fans that gradually grew into a large community with the power to change the world. These small projects will bring our cities to life and bring forth new ‘local’ brands.

Starbucks, for example, still identifies itself as a Seattle brand. Similarly, Terarosa Coffee in Korea has kept its roots in Gangneung. CEO Jong-Duk Kim of Terarosa Coffee was the Managing Director of a bank in Gangneung until the Asian Financial Crisis hit. After voluntarily resigning from his position, he, unsuccessfully, turned to the restaurant business. He shifted his focus to the coffee business when he noticed an opportunity in the then-nascent premium coffee market. At the time when he started his coffee business, the coffee market in Korea was limited to cheap coffee from vending machines. CEO Kim gained a competitive edge over these machines by building a coffee machine that offers new menus, such as latte and espresso coffee. Others, including Yi-Chu Park’s Bohemian Roasters, opened businesses in similar fashion by leveraging different characteristics of their neighborhoods, turning Gangneung into a city of coffee. Not a dime of money used in this process was backed by the local administration nor the central government.

For older generations, these business projects may appear to be another set of urban regeneration projects. Young people, on the other hand, would say that there are striking differences between the two. They gather in these places because of their interests, the community, and because it allows them to create the type of city that they desire.

I believe that these rural regions are experiencing difficulties that urban regions will face in the future. Though the population is still concentrated in cities like Seoul and Tokyo, there is no doubt that the future is already here in these rural regions.

FOLLOW-UP DISCUSSIONS

The following is a summary of the discussions between Director Han and the participants of the seminar.

- Sustainability is just as important as creativity. It seems insufficient to support businesses that seem to be a flash in the pan.

“I agree but disagree in part. It is true that many of these small businesses have many shortfalls, and for these young entrepreneurs, opening a business is merely a means to an end: to attain happiness. Sustainability, is of course, very important. However, business localization by younger generations did not start just yesterday. From what I gather, the movement started roughly in 2010, and currently, we are at a point where these people are attracting real investments. They are generating their own traction. And we are only in the early stages of this, so I believe that these businesses will be able to achieve sustainability on their own. What is important now is to encourage and support these people, instead of doubting their potential.”

- Are there any examples of businesses that have successfully applied the value-based approach?

“Nike, for example, still has its roots in its hometown of Portland, and the same can be said for IKEA and Nestle. These businesses kept their roots in their hometowns because it is profitable, and because it generates considerable advertising value by creating a positive brand image. And while some local ventures only aim to stay afloat, others strive to become national brands. Over time, these businesses will engage in discussions and competitions to ultimately create a local ecosystem or a ‘local scene’.”

- We are still seeing new town developments around Seoul. Professor Jong-Ryn Mo opposed the idea of constructing additional new towns and said that these new towns will also have to create their versions of ‘local’. What are your thoughts on this matter?

“I heard Gwanggyo New Town incorporated Tadao Ando style in its design. However, I think such attempts fail to capture the essential part of local consumption, which is the combination of local life and style. Nonetheless, ‘local’ is definitely gaining traction, and things should be different from the ‘local bubble’ 10 years ago.”

“I agree with Professor Mo that Korea does not need additional new towns. Instead, we have to make an orderly exit out of new town projects altogether. Right now, if you visit rural places like the Gangwon province, you will find that farms and fields have turned into jungles, because people who own the land neither farm nor sell the land. This is why we have to make more investment in our local areas.”

- What are your thoughts on ideas like open innovation?

“We at the CCEI have, of course, considered the idea. However, the National Assembly is yet to take the initiatives in corporate venture capital (CVC) and open innovation. Right now, investments in local regions are stalled because local venture investors find it difficult to make reinvestments when they have not earned the profits they need to meet the principal.”

< Copyright holder © TAEJAE FUTURE CONSENSUS INSTITUTE, Not available for redistribution >